John Spencer and Jayson Geroux | 01.13.22

The battle of Suez City occurred on October 24–25, 1973 during the Arab-Israeli War (also known as the Yom Kippur War), which began on October 6 of that year and ended on October 25 Suez City is located at the very northern end of the Gulf of Suez and rests on the northwest bank of the Suez Canal’s southern entrance. There were three main roads that entered the city, each of which passed through a large gate at the city’s limits: heading north from the city was an asphalt road leading to the city of Ismailia; Route 33 left the city to the northwest before curving west toward Cairo; and to the southwest was the road to Adabiah. The Sarag Road was the main thoroughfare through the city. It ranged anywhere from seventy-five to two hundred meters wide, had a concrete wall as a center median. The road began at the port and ran through the city, effectively cutting it in half, before becoming Route 33 and leaving toward Cairo. Other roads also gave access to the city, although these also passed through gates, and not all of these gates were large enough for vehicles. The southern sections of the city had an industrial area to the southwest and Port Ibrahim (now Port Tawfiq) to the southeast, which sat at the end of a 1.5-kilometer causeway that jutted out south and then southwest into the gulf. Large oil refineries were located to the west of the city limits. To the east of the city and along both sides of the Suez Canal was dense vegetation called the “greenbelt,” which impeded observation and off-road vehicle movement. Sandwiched in between the eastern edge of the city and this dense vegetation beside the canal was a marshy area along Suez Creek that was impassable to vehicles.

The Battle

The city’s defenders were sub-units of the Egyptian 3rd Army with remnants of the 4th, 6th, and 19th Divisions, giving an aggregate strength of two mechanized infantry battalions, an antitank missile company, a commando battalion, military police officers, artillery forward observer teams, and a small number of T-54/55 tanks, all under the command of Brigadier General Yussif Afifi. There were also two thousand militia that had been given incremental training by retired Egyptian Army officers. Attacking the city was Israeli Major General Avraham Adan’s 162nd Armored Division consisting of Colonel Gavriel “Gabi” Amir’s 460th Brigade, Colonel Aryeh Keren’s 500th Brigade, and Colonel Nathan “Natke” Nir’s 217th Brigade. To compensate for his lack of organic infantry General Adan was reinforced with an armored infantry battalion that was attached to Keren’s 500th brigade. Colonel Keren’s brigade was also reinforced with a paratrooper “battalion” under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Yossi Yaffe consisting of only 160 soldiers, nine Topaz amphibious armored personnel carriers, and three buses as transport; eighty paratroopers mounted in three trucks and two half-tracks commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Yaakov Hisdai; a scout company; and a company-sized reconnaissance unit.

On October 6, 1973, the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria launched a surprise, two-pronged attack against Israel. Once they recovered, the Israel Defense Force (IDF) successfully counterattacked in the northern and southern theaters to drive the invaders back to their start lines. In the southern theater, Major General Kalman Magen and Major General Adan were to advance their armored divisions west and then south past the Bitter Lake to remove all Egyptian rocket sites while Adan was given the additional task to “dash” to Suez City. The “dash” took five days and robbed Adan of the time needed to properly attack an urban area. By the time he reached the area, he had less than six hours to formulate a plan and attack the city before the United Nations–imposed ceasefire took effect at 7:00 a.m. local time on October 24 and the arrival of United Nations Truce Supervisory Organization troops to enforce the ceasefire. Also, Adan had to task a majority of his division’s infantry forces to hold captured materiel, guard prisoners of war, and clear sections of the greenbelt near the Suez Canal.

On October 24 at 1:30 a.m., General Adan was directed to clear the greenbelt, to cut off the water pipes flowing from the west to east bank that were supplying enemy forces on the east side of the waterway, and to capture Suez City—“provided it does not become a Stalingrad situation.” At the operational level, capturing Suez City would tighten the IDF’s siege and encirclement of the Egyptian 3rd Army.

General Adan immediately requested an intelligence report on what enemy forces were in the city and then set about creating his plan, giving orders to his subordinates at 5:20 a.m. He received the intelligence report at 5:50, and the report confirmed essentially what he already knew: that he would be facing at least two mechanized infantry battalions, an antitank missile company, and a commando battalion. Although he knew the city was not empty by any means he anticipated that the Egyptian forces in the city would be disorganized and rapidly collapse based on the many numbers of enemy prisoners of war taken as his and General Magen’s divisions had advanced southward over the past several days. It appeared to both Adan and Israeli military intelligence that Egyptian forces were in disarray and retreat.

Israeli doctrine at the time prescribed the isolation of the urban area with armored units occupying key terrain outside of the city while remaining forces assisted the encirclement, and then a quick and decisive armored thrust into the city with several columns of tanks, armored personnel carriers, and engineer vehicles that were to achieve shock action and capture the city itself. Mounted infantry forces following behind the armored columns were used to attack pockets of enemy dismounts. This procedure—tanks advancing and leading the attack alone, with mounted infantry following behind—worked when the IDF attacked urban areas in 1956 and throughout the Six-Day War in 1967 so it was viewed as viable. A mindset that “tanks can do it all, alone” became enshrined in Israeli doctrine as a result.

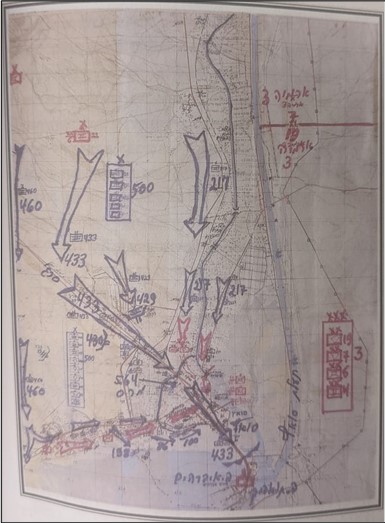

General Adan’s plan for capturing Suez City was to begin with a large-scale series of airstrikes and a three-battalion artillery bombardment. Both of the brigades would have to first advance several kilometers, attacking and mopping up enemy camps en route, and then form up with their attachments at the edge of the city. Adan’s main effort was Colonel Keren’s 500th Brigade, which would attack from the northwest along Route 33 to capture key intersections within the city, where the route turns into the Sarag Road, and then have a second echelon pass through, advance to Port Ibrahim, and capture the port. Colonel Amir’s 460th Brigade would attack from the west, take the industrial zone and refineries, and then advance to the Suez Gulf and follow it eastward, linking up with the 500th Brigade at the port. Adan’s third brigade, the 217th, led by Colonel Nathan “Natke” Nir, was to mop up the greenbelt northeast of the city with a majority of the division’s infantry soldiers. Each brigade had approximately sixty tanks to lead its charge into the city, with the attached infantry paratroopers following in their armored personnel carriers, half-tracks, and buses. Although there were soldiers in the paratrooper units who had conducted urban operations during the Six-Day War in 1967, none of these soldiers had ever worked with tanks in an urban environment before. Given the condensed timelines for the operation, lack of infantry support, previous success with armor leading the charge in urban areas, and a belief that Egyptian forces would be quick to capitulate, this was the plan that Adan put into action.

Unfortunately, Egyptian defenses in the city were considerably stronger and its defenders considerably more motivated than the Israelis believed. Planning for the city’s defense had begun a year earlier with a military-civil government that assumed complete authority over all military, civilian, and civil government assets when war occurred. Approximately 60 percent of the civilians were evacuated from the city and only two thousand essential workers—including government officials, police, firefighters, bankers, food suppliers, businessmen, medical personnel—remained behind. These personnel were organized into groups, given weapons training, and commanded by Egyptian military officers so they could work with the 3rd Army’s forces. The city’s three largest gates were prepared for demolition and overwatched by antitank Sagger and RPG weapons teams while the smaller gates were destroyed and blocked with mines and rubble prior to the battle. The width of the main streets in general and the Sarag Road in particular allowed for extremely good kill zones for antitank teams and ZSU-23 antiaircraft guns. Many antitank team personnel positioned themselves on the city’s easily accessible flat rooftops or upper floors with large open windows. These elevated positions provided good hiding spots, observation, ventilation for weapon systems, and firing positions with little worry about being seen or the effects of weapons’ backblast. Other buildings that were blocking good fields of fire were destroyed completely. Small arms and machine-gun positions were placed in the first two floors of strongly constructed high-rise buildings so that Israeli artillery fire could not destroy them. The T-54/55 tanks were placed in the northeastern portion of the city to overwatch the city limits as well as observe and, if necessary, fire upon a bridge crossing a nearby canal. A defensive fire plan was also created using the artillery units located on the Suez Canal’s east bank. Artillery and reconnaissance teams selected positions in taller buildings that gave them good fields of observation and the ability to adjust fire if necessary. Command posts and supply caches were cleverly established in bank vaults where they would be extremely safe. Other large buildings also housed quantities of food and other essential supplies. Communication methods were centralized so that civil and military personnel could talk to each other easily. If radio communications failed, friendly noncombatants stood ready to act as couriers. Brigadier General Afifi directed all units to hold their fire until the IDF had penetrated deep into the city to maximize the number of Israelis that would be destroyed in the numerous kill zones. This deception would give the Israelis the impression that the city was not held in strength and allow the Egyptians to inflict the maximum amount of damage on the attackers.

On October 24 the Israeli attack started under a morning mist and a psychological sense of urgency knowing UN personnel would soon arrive. Both these factors greatly inhibited the initially scheduled preattack air and artillery strikes, causing, in General Adan’s own words, “a pretty poor softening up” of the city defenses. Colonel Keren’s 500th Brigade dealt with some enemy tanks and antitank guns on the city’s periphery but the brigade waited at the outskirts for the paratroopers to arrive as they had been clearing small enemy camps north of the city en route. Colonel Amir’s 460th Brigade began attacking at 8:20 a.m. and gained a lodgment in the industrial zone. An armored column rapidly advanced to reach the outskirts of Port Ibrahim while the remaining forces stayed behind in the industrial zone’s housing district to mop up the defenders. Everything had gone more or less as planned for the 460th Brigade. However, Keren’s 500th Brigade was still waiting at the northwest corner of the city for Lieutenant Colonel Yaffe’s paratroopers. General Adan directed Keren to break in and gain a lodgment. When the paratroopers arrived shortly before the attack began, Keren gave Yaffe thirty minutes to prepare and then decided apprehensively to have the 433rd Armor Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Nahum Zaken lead the attack. The tanks were sent down the Sarag Road towards three road junctions. To maximize the shock effect of the tanks, they were told to move swiftly towards their objectives firing at enemy positions but not stopping on their way. Lieutenant Colonel Yaffe’s and Hisdai’s paratrooper groups and the brigade’s scout company were to follow.

At 10:15, Keren’s brigade advanced with Zaken’s 433rd Armor Battalion, composed of a mixture of tanks, armored personnel carriers, and half-tracks. Yaffe’s paratroopers followed in Topaz armored personnel carriers and buses but the space between the two groups widened due to the speed of the tanks in front. When the enemy opened fire on the armored battalion at the canal bridge, the paratroopers dismounted but were immediately directed by the deputy brigade commander to remount to catch up to the armored column, which was now speeding away. After they eventually remounted, the entire column of tanks and paratrooper vehicles was now stretched out over two and a half kilometers, with gaps of around five hundred meters between some groups of vehicles.

When the 433rd Armor Battalion—now without the infantry paratroopers—came to the second key intersection the world exploded: antitank missiles, ZSU-23 antiaircraft guns, and small arms suddenly opened fire simultaneously. The lead tanks and those at the end of the column were hit first to trap the other vehicles in the middle. Within minutes a majority of the senior leaders and tank commanders were personally hit. Israeli tank commanders often rode with their hatches open to observe and direct the fight around them; now most of their bodies were slouched over in their turrets, wounded or dead. Without their leaders, many soldiers had no idea what to do next because the compressed time in preparing for the attack had meant subordinates did not understand their complete mission. The airwaves were full of soldiers crying for help on the radio. Many drivers of the armored vehicles were dead, which left tanks sitting in the streets taking round after round and blocking other tanks from maneuvering. Those drivers who were able to move their vehicles turned to withdraw or ducked into narrow alleyways where they were ambushed and destroyed; and tanks were blocked by the center median’s concrete wall, canalizing them on either side of the street. Amazingly, Lieutenant Colonel Zaken was still alive and took control on the radio, scrounged up whatever remaining forces he had, and drove quickly out of this kill zone and down the Sarag Road toward Port Ibrahim.

When Yaffe’s paratrooper column arrived at the intersection, the world exploded again. Many paratroopers became casualties immediately, with three killed and eighteen wounded—including Yaffe—in the opening salvo. Egyptian soldiers threw Molotov cocktails and grenades from second-story windows into the open-top half-tracks and onto the buses. Egyptian Hosam grenades—their magnetized bottom allowing them to stick to a vehicle’s armor—were placed by dismounted enemy forces ducking in and out of alleyways. The paratroopers that were not killed or wounded dismounted and entered buildings for protection.

Lieutenant Colonel Hisdai’s paratrooper group, still back by the first intersection and hearing the fight ahead of them, dismounted and moved by foot. They came under fire and also took cover in nearby buildings. The scout company that was following the paratrooper groups also received an overwhelming amount of fire and took sixteen casualties in the first salvo. They withdrew from the immediate area.

By 11:00 a.m. the attack had culminated. Amir’s 460th Brigade had met its objectives. However, Keren’s 500th Brigade was spread out on all three of its objectives along the Sarag Road—the much-depleted armored column near the port with no infantry support and both paratrooper groups back at the other two objectives, isolated and pinned down. Air support was called in to try and help but due to the unknown locations of friendly forces the close air support struck at enemy positions at the port, which did nothing to help relieve the 500th Brigade.

Lieutenant Colonel Yaffe’s paratroopers cleared a police station but were soon low on ammunition and water, and communications were intermittent due to the surrounding buildings blocking the radio transmissions. The Egyptians soon discovered where this group of Israelis was located and took positions in the surrounding four- and five-story structures, employing marksmen, small arms fire, and grenades to conduct several dismounted attacks against the station. One Egyptian soldier even got as far as the room that contained the wounded when he was gunned down at the door. The paratroopers were told to hold out and wait to be rescued by an armored column. They were told to throw chairs outside of the building so the armor soldiers could identify their exact location. The attached artillery officer called for a fire mission to stop any further attacks.

At 11:30 General Adan had decided he must relieve Keren’s 500th Brigade and break the Egyptian defenses by having Amir’s brigade leave the port, turn northwest, and link up with 500th Brigade; his two-brigade attack had now become a one-brigade rescue. However, this force was held up clearing the Cleopatra Hotel en route because of its size and location. The building turned out to be empty. The advance became even more challenging as large numbers of the two-thousand-person civilian militia had been busy erecting impromptu barriers while also carrying supplies and relaying information about the Israeli locations to Egyptian soldiers. The rescue force of Israelis took twenty-three casualties as Egyptian soldiers and militia continued to shoot, throw grenades, and toss Molotov cocktails into the open-top half-tracks that attempted to get around the improvised barriers. With the advance bogging down and casualties mounting the column turned around and withdrew back to Port Ibrahim.

Adan now realized that his beleaguered forces were not going to capture Suez City and that his main task was to rescue those who were now trapped within it. He told his brigade commanders that all efforts were now focused on liberating the paratroopers. He directed Nir to dispatch a mechanized reconnaissance battalion with its nine BTR-50 armored personnel carriers, 150 soldiers, and five tanks to leave the greenbelt and penetrate the northeast corner of the city to link up with Keren. This column drove southwest into the city’s heart. At one of the first intersections, the two lead tanks continued southwest but the remainder of the column turned northwest onto the Sarag Road. This group immediately came under fire from every direction, taking numerous casualties. The column pressed on to the police station but did not see the piles of chairs on the side of the road in front of the building—so they drove right past Lieutenant Colonel Yaffe’s paratroopers. The two lead tanks that had continued southwest had since realized that they were alone, turned around, and made their way back up to the Sarag Road, where they turned and drove northwest, also missing the piles of chairs driving past Yaffe’s paratroopers. The reconnaissance battalion continued northwest and despite the heavy fire recognized Lieutenant Colonel Hisdai’s paratroopers in the buildings. Keren immediately tasked the scout company that had now made it to his location to follow the reconnaissance battalion back to Hisdai’s paratroopers’ location. It was now 4:00 p.m., but the column returned to the position quickly, fired furiously in every direction, mounted up the paratroopers in armored personnel carriers, and withdrew, leaving Hisdai and six others behind due to there being no room in the vehicles.

General Adan still had paratroopers within the city at dusk. Having another vehicle column advance into the city would not work given the day’s events. To advance at nighttime would be even more foolish. Waiting until the next morning would probably have led to the death of the paratroopers, as well, since the Egyptians would likely overrun their position during the night. Adan directed that although it meant moving with their casualties the paratroopers had to extricate themselves. Hisdai and his six paratroopers extricated themselves successfully in the early evening. Yaffe’s group of ninety paratroopers extricated themselves beginning at 2:30 a.m. on October 25, moving along side streets and bypassing Egyptian positions to link up with friendly forces at 4:45 a.m.

The casualty figures for the Egyptian forces are unknown as they were never recorded. Israeli casualties totaled eighty-eight killed in action, 120 wounded in action, and twenty-eight armored vehicles destroyed. A large number of Israeli soldiers also suffered from mental health challenges after the battle. Lieutenant Colonel Hisdai found that even those paratroopers with prior urban combat experience from the 1967 fighting in Jerusalem suffered debilitating stress injuries from the fight in Suez City. After the war many grieving Israeli families questioned the wisdom of storming a city whose capture was clearly not essential for the defeat of the Egyptian 3rd Army.

Lessons Learned

There are several lessons—at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels—that can be drawn from the Battle of Suez City. First at the strategic level, to assume urban battles will only occur because the objective is to dislodge an enemy force from a city demonstrates a myopic view that ignores the larger picture. While it was important for the Israelis to encircle the Egyptian 3rd Army to strengthen Israel’s position during the postwar negotiations there was also the need to rapidly seize what they believed to be a piece of critical terrain. Suez City’s location was strategically important. Situated at the southern entrance of the Suez Canal, it held the high ground from which to exert disproportionate influence over global commerce. The city’s capture by Israeli forces was also strategically important because it would disqualify Egypt’s public—and false—claims to their own citizens that they were destroying the IDF in mass numbers. Information warfare often rests at the strategic level because it wins over populations and influences mass opinion, thus influencing political leaders. The Israelis understood the wider implications of trying to take Suez City—they recognized that it was not just about the enemy. These other strategic factors must also come into consideration when senior political and military leaders decide that they must fight an urban battle.

A second strategic lesson is that senior political and military leaders must caution against an urban “last minute grab,” which is how General Adan described the battle after the war. In fairness senior Israelis believed there were a number of reasons to attempt the capture of Suez City: the IDF had pushed Egyptian forces back across the Suez Canal; the city controlled the southern access to the canal itself; they wanted to demonstrate to the Egyptian people that the Israelis were on the offensive; there was an urge to take the city before a UN peacekeeping force imposed its ceasefire; Israeli urban tactics, with swift armor strikes, had been successful in previous conflicts; and the encirclement of the Egyptian 3rd Army was too tempting to resist. However, even in the presence of such an apparent confluence of reasons to take an objective—and to believe it can be done successfully—there must remain an application of caution when it comes to urban areas. Any political interests in capturing a city must be weighed against military realities and historical examples of the requirements involved, including the amount of time, intelligence, and forces needed for planning and executing the mission.

The first major operational lesson from this battle centers on the difficulty of achieving an accurate intelligence picture in the urban environment. Israel had a completely incorrect understanding of the enemy forces and their defenses in Suez City and they paid the price for that lack of accurate intelligence. Urban environments require more human, signal, imagery, open-source, and other forms of intelligence collection than any other terrain. The complex physical and human contexts of dense urban terrain compound the difficulty of obtaining accurate and timely intelligence to support rapid operations. The complexity of an urban area means attempting to conduct operations relying on speed rather than intelligence is a gamble, not a risk; it is brash, not bold. The solution is time, and although it can be a strategic variable, time must be taken to conduct a proper intelligence preparation of the urban environment. While some modern technologies may help, the complexity of conducting reconnaissance and intelligence gathering in dense urban areas remains. At the operational level this intelligence gathering and analysis could take weeks—maybe even months—to occur. However, lives and resources will be saved as a result, which is considerably more strategically and operationally palatable.

A second operational-level lesson is that defending a piece of urban terrain can be valuable for several identifiable reasons: it can delay and even halt a force on the offensive, it can make the offensive force pay dearly in casualties, and, as was the case at Suez City, it can create the time needed for political action. The Egyptians’ year-long preparations for the defense of the city, their training and effective use of the local militia, their detailed complex ambushes, and their scheme of maneuver—which had the illusion of weakness, thereby luring the Israelis deeper into the city, where they were struck heavily with different weapon systems—all worked for the defenders. This in turn allowed for that critical purchase of time that was needed before the UN ceasefire was put into effect—bogging down Israeli forces in the city so they could not exploit their growing momentum and seize more land ahead of the ceasefire and subsequent negotiations. Historically, a force defending urban terrain will often lose the fight, but also make it extremely costly for the attacking force to achieve victory. However, Suez City provided an example of the extreme opposite: the defending force did not lose the urban fight at all. Normally the defender has the advantage because the urban terrain can be used for concealment and cover both to fight from and to maneuver. Attacking forces cannot use their surveillance, reconnaissance, or aerial assets to full effect, buildings can serve as fortified bunkers, the defender maintains relative freedom of maneuver in urban terrain, and the defending forces can use subterranean systems to their advantage. However, in most cases, if the offensive forces are employing appropriate operational and tactical procedures, they will eventually win. Suez City seemed to prove that defenders can win an urban fight, providing the offensive force makes strategic, operational, or tactical mistakes—that compound one another—in sufficient numbers.

At the tactical level, a major lesson drawn from an analysis of this battle is that armor assets must be used—and protected—in urban combat. Infantry protects armor and armor protects infantry. Suez City demonstrated the disastrous results of tanks and infantry fighting separately. The Israelis believed that swift urban strikes led by armor were the key to success: this tactic had worked in 1956 and again in 1967. However, the big difference between those two earlier conflicts and the 1973 war was that in the former two the Israelis went on the offense, moved swiftly, and surprised their enemies completely. As a result, their opposing forces did not have the time to prepare adequate urban defenses. The 1973 war was entirely different: the Egyptians had been planning the urban defense of Suez City for almost a year and were not surprised at all when Israeli forces entered the city. Several facts of the Israeli attack proved devastating. First, the Israeli 500th Brigade’s armored columns were spread out and could not protect themselves as they speedily made their way deep into the city. Second, Israeli paratroopers were not colocated with the tanks and had not conducted any urban operations training with tanks at all. And third, all of the 162nd Armored Division’s organic infantry units were on another operation. These problems only compounded the losses in Israeli tanks, vehicles, and personnel in the city. Urban warfare history is replete with examples of both the importance and the proper use of armor. Without the use of armor in urban operations victory will be long delayed—if achieved at all. To achieve rapid victory, armor must be used but well protected by infantry, engineers, artillery, and the weapon systems they employ so that a symbiotic relationship between the armor and these other combat arms exists and all are working together to defeat the enemy.

The final tactical lesson of the Battle of Suez City is that negative repercussions can occur when a military unit is suddenly grouped together and given an unfamiliar task under hurried circumstances and on a type of terrain for which they are not trained. Most of the organic infantry forces under General Adan’s command were given to Nir’s brigade to clear the greenbelt. Two paratrooper “battalions”—in reality, one company-sized unit and one with company-minus strength—were then attached to Keren’s 500th Brigade without having had time to assimilate into the unit and rehearse combined arms tactics in the urban environment. In retrospect, it would have been better had Adan kept a majority of his organic infantry and only given a small portion of it, along with the paratrooper units, to Nir for the greenbelt task. This way, the remaining organic infantry and the armor forces that had been working together since the beginning of the conflict would have been able to continue and perform better—provided they were fighting the battle as one team and not separated. Assuming there is time to rapidly combine combat arms so quickly is a major tactical risk in any environment—even more so when it comes to the complexities of urban warfare. In this case it contributed to the heavy casualty toll paid by the attacking Israeli forces.

Conclusion

Most urban operations throughout history have ended with the offensive force achieving victory. Rarely has an urban battle occurred where the defenders clearly succeeded. Most historical cases show that even though there were a high number of casualties on both sides, the offensive force eventually won regardless. However, the Battle of Suez City is one of the rare cases in urban warfare history where the offensive force committed so many strategic, operational, and tactical errors and the defense was so well planned and executed that the defenders achieved victory. The lessons that the battle provides are unique and important for future urban operations in which an attacking force has as its objective the capture of a city.

A special thank you to IDF historian Colonel (res) Boaz Zalmanovich and Dr. Eyal Berelovich from the IDF Ground Forces Land Warfare Research Institute for their review of this case study.

Colonel (CA) John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, codirector of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He previously served as a fellow with the chief of staff of the Army’s Strategic Studies Group. He served twenty-five years as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq.

Major Jayson Geroux is an infantry officer with The Royal Canadian Regiment and currently with 1st Canadian Infantry Division Headquarters. He has been involved in urban operations training for two decades and is a passionate student of urban operations and urban warfare historian, having participated in, planned, executed, and intensively instructed on urban operations for the past seven years. He has served twenty-six years in the Canadian Armed Forces, which included operational tours to the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia-Herzegovina) and Afghanistan.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or that of any organization with which the authors are affiliated, including 1st Canadian Division Headquarters, the Canadian Armed Forces, and the Canadian Department of National Defence.

Image credit: IDF Spokesperson’s Unit (adapted by MWI)

Urban Defenders, just by manning their Wall (delapidated though they may be) have won countless battles down through the ages, since the time of Rome…

…every time an Attacker turns aside and seeks easier, less deadly prey, Urban Defenders can claim a victory.

If we only count those times that Attackers “attack”… think on that a moment. Attacks only come once those attacking have provisioned themselves for the extended siege, have seized the Defenders into starvation and disease, and have demoralized the defended population… counting only those instances, is a disservice to the Millions of Lives saved each day that Stout Walls and Stalwart Hearts had turned aside a flood of would-be conquerors.

I was there in one of 4 M109s. 2 were fireing direct at entrance to Suez City and 2 at the refinery firing into the city.

President Sadat led a high level intelligence war, prepared everything and fooled others by taking Sinai and depriving them from any tangible success

Thank you for the article.

Please would you add a bibliography?

Some of the weblinks no longer work, so bibliographical details are needed to search for the relevant sources.

In particular, the following Canadian Army link does not work, as that entire website appears to have been taken down:

https://armyapp.forces.gc.ca/SOH/SOH_Content/B-GL-322-007-FP-001%20(2006).pdf