John Spencer and Jayson Geroux | 06.28.21

The Battle of Stalingrad (modern-day Volgograd) occurred from August 23, 1942 to February 2, 1943 during World War II (1939–1945). The city is in the southwestern region of what was then the Soviet Union. The majority of the city rests on the west bank of the Volga River 970 kilometers southeast of Moscow. The Volga flows southwesterly into the city, passing through it before turning directly east and then curving gently to the southeast toward the Caspian Sea.

The Battle

The battle was fought by the Axis powers of Army Group B—principally the German 6th Army commanded by Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus within the city—and the Soviet Union’s Stalingrad Front and its subordinate 62nd Army (commanded by General Vasily Chuikov) and 64th Army (commanded by General Mikhail Shumilov). Known as the biggest defeat in the history of the German Army, the battle destroyed Germany’s reputation of invincibility and sent the country into a more-or-less defensive mode for the duration of the war. The battle nearly guaranteed that Germany had begun the path to defeat on the Eastern Front.

The German Army Group South’s original strategic intent was to advance to and seize the Caucasus oil fields but German leader Adolf Hitler’s additional strategic desire to capture the city named after his rival, the Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin, was too tempting to refuse. The city was also an attractive target because it produced Soviet armored fighting vehicles and other military equipment. Seizing the city would allow half of Army Group South to provide a certain level of protection to the other half by shielding the latter’s northeastern flank as it advanced to the Caucasus; thus, its capture at the operational level was considered crucial by the Germans. Hitler thus split Army Group South into two smaller army groups, with Army Group A continuing south toward the Caucasus while Army Group B diverted east toward the city.

In the opening months of the battle the German 6th Army drove hard for the city while the Italian 8th Army and Romanian 3rd Army guarded Army Group B’s northwestern flank along the meandering Don River and the German 4th Panzer Army and Romanian 4th Army guarded the southeastern flank along the salt lakes south of Stalingrad. Initial fighting for Stalingrad’s outskirts began on August 23, 1942 with an opening air offensive. The 6th Army’s Germans ground their way forward against the 62nd and 64th Armies’ Soviets, aided by the Luftwaffe and German artillery, which slathered the city with thousands of tons of high explosives and destroyed most of the city’s buildings. With an influx of refugees caused by the war, the city’s population was over nine hundred thousand by 1941 and although many had left a large number remained within the city, resulting in the deaths of an estimated forty thousand Russian civilians who were working in the military factories. The Soviets used the great amount of destruction to their advantage by adding man-made defenses such as barbed wire, minefields, trenches, and bunkers to the rubble, while large factories even housed tanks and large-caliber guns within.

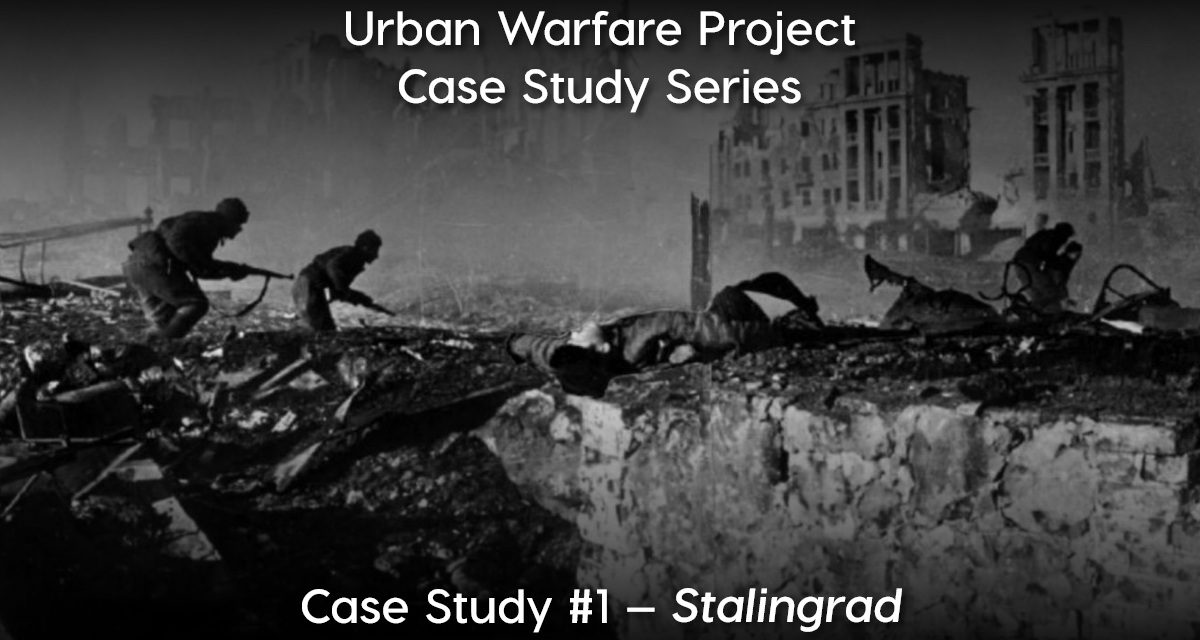

The fighting in Stalingrad quickly turned into some of the most high-intensity urban combat in history. It was urban combat at its worst. The level of violence and resulting destruction between the two sides became truly unimaginable as the Germans pushed to capture the extreme northern and southern ends of the city by the end of August. German tactics followed a successful pattern: Luftwaffe airstrikes, then artillery, then advancing infantry with tanks in support. Unfortunately there were never enough artillery, infantry, and tanks to do the job swiftly and although the pattern was effective it still came with a high cost in casualties. Two large German offensives throughout September and October forced the Soviets to occupy only a nine-mile-long north-to-south strip that was only two to three miles wide along the west side of the Volga. The Soviets only held the narrow sliver of land by throwing consistent reinforcements to prevent them from reaching all of the Volga within the city limits. The length and width of the Volga itself prevented the Germans from encircling and isolating the city. This allowed the Soviets the ability to continually brave the repeated German Luftwaffe and artillery strikes as they ferried reinforcements across the river and into the urban fight. The Germans continued fighting into November with small raids and attacks that often degenerated into several days of sustained, lethal urban combat with little result but many casualties.

During the fighting, the Soviets recognized that the Italians and Romanians guarding the German flanks were a potential weakness and had throughout the autumn months increased the number of Soviet armies on both the northwestern and southeastern flanks to total over seven hundred thousand soldiers with 1,400 tanks. Along with the Stalingrad Front, the Southwestern and Don Fronts (each equivalent to an army group) launched Operation Uranus (November 19–23, 1942) with the intent of crushing the Italian, Romanian, and German armies around Stalingrad, linking up someplace west of the city and thus encircling the 6th Army within the city itself. On November 23, the two Soviet advances—the Southwestern and Don Fronts from the northwest and the Stalingrad Front from the southeast—met at the village of Kalach, just west of Stalingrad, and completed the task of encircling the Germans. With the 6th Army’s logistical ground support now unavailable, the Luftwaffe attempted to resupply Paulus’s troops by air for the next several weeks but the meager sixty tons of supplies a day was far short of the 550 tons needed daily by the 6th Army. The Soviets also limited the aerial resupply by advancing southwest away from the city to increase the distance between the German airfields and Stalingrad while also emplacing antiaircraft artillery guns to destroy attempted resupply runs.

While the Luftwaffe tried to resupply the 6th Army the Soviets now went on the offensive, the intensity of fighting within the city becoming more violent. Hundreds of “shock groups” consisting of fifty to a hundred soldiers broke into small groups to fight as highly lethal and lightly armed infantry-engineer squads of three to five personnel, moving swiftly and silently throughout the rubble or “hugging” the Germans near the frontlines to avoid the effectiveness of German airpower and artillery. Dozens of snipers took advantage of the destruction to find nearly perfect firing positions. Snipers successfully killed hundreds of German soldiers, providing a psychological boost to the Soviets while lowering German morale tremendously. Soviet tanks were used in a way that would unnerve armor crews of today: instead of being used for maneuver they were dug deep into the rubble, camouflaged, and used as pillboxes, their carefully prepared positions remaining unseen until they fired the first shot from just a short distance away. These tactics took a devastating toll on German personnel and vehicles over the following months.

Buildings and floors within Stalingrad changed hands dozens of times, and sometimes platoons and companies took several days and up to 90 and even 100 percent casualties just to win a building or a floor within it. Entire battles were fought over single buildings or complexes with names like the Martenovskii Shop, Pavlov’s House, the grain elevator, and the Commissar’s House. To add to the Germans’ misery, Russia suffered its worst winter in almost half a century with the temperature well below freezing on most days, conditions that became even worse at night or during severe winter storms. Thousands of Germans became medical casualties from both combat and the cold weather as a result, while the Soviets, acclimatized to such conditions, continued to grind away at German numbers with an almost unending violence.

Paulus, whose Army’s numbers throughout December 1942 and January 1943 were being reduced in vast quantities daily and with a majority of his soldiers on the brink of starvation, defied Hitler’s orders to fight to the bitter end; Hitler implied to Paulus, who had been promoted to the rank of field marshal during the battle, that he should commit suicide rather than capitulate. Paulus surrendered on February 2, 1943. The casualties on both sides were horrendous—the result of two dictators feeding men, materiel, and machines into an urban fight all for the sake of taking or defending the city named after one of them. German casualties were estimated at four hundred thousand men with ninety-one thousand prisoners. Soviet casualties were estimated at over 750,000. Historians have remarked that Stalingrad was the turning point of the fighting on the Eastern Front as it was the first public and large-scale loss suffered by the Germans in that theater of the war. It also demonstrated high-intensity urban combat at its most violent and brutal under the most challenging of weather conditions.

Lessons Learned

There are many lessons that can be taken from the battle. However, any appreciation of those lessons must be tempered by the caveat that some of them may not be applicable to present-day militaries. For example, Stalingrad took place in a theater with a large number of army groups with a total of a million soldiers involved on each side; modern armies are unlikely to fight with these numbers. Thus, the analysis on the lessons learned for Stalingrad will focus on those that can be applied to the present environment.

Strategically, Stalingrad illustrates that the reasons a nation would engage in high-intensity combat in dense urban terrain against a peer adversary may not be rational. The city was not a decisive piece of terrain for either side, but political reasons came to the fore: Hitler wanted to take the city named after his rival, Stalin; Stalin wanted to ensure that his namesake city did not fall. Arguably the battle was fought more for pride than for rational military or national objectives.

Operational reach is a function of intelligence, protection, sustainment, endurance, and combat power relative to enemy forces. The limit of a unit’s operational reach is its culminating point—the point at which a force no longer has the capability to continue its form of operations, offense or defense. The ability to resupply an army can become more important than tactical capabilities. In high-intensity urban operations a higher number of resources will be needed: four times the amount of ammunition required in non-urban environments and up to three times the amount of consumables such as rations and water are the norm. Operationally, then, Stalingrad emphasized the necessity of a military’s recognition of its own limits of operational reach and its culmination point. Once German forces could no longer be resupplied, they were defeated.

Due to the scale, duration, and intensity of the battle, Stalingrad offers enough tactical lessons to fill entire books. The importance of combined arms in urban operations was clearly one of the most important lessons demonstrated. After-action reports of the battle discussed how German armor was too vulnerable to enemy fire and worked better as fire support behind the infantry. Combined arms teams—armor, infantry, engineers, and fires from artillery and mortars—must be trained together to achieve the high level of cooperation, teamwork, and tactical capability required by high-intensity combat in dense urban terrain.

Heavily fortified urban infrastructure becomes critical in an urban defense and becomes major obstacles in an attack. At Stalingrad, entire battles fought over single buildings or complexes occurred frequently and lasted for hours, days, and sometimes weeks. Defenders must plan to use fortified buildings as strongpoints, while attackers must have plans to negotiate or reduce these structures. That does not necessarily mean just using heavy fires to eliminate strongpoints, although that is a consideration; the use of fires—aerial bombing, artillery, and mortars—are not the single solution. Stalingrad shows that fires alone do not eliminate defending enemies embedded deep in the urban terrain. The benefit of fires must also be weighed against how it will change the terrain for the attacker. Rubble limits maneuver and the effectiveness of critical capabilities like tanks.

The use of subterranean systems rises with the lethality of combat in urban terrain. Some soldiers described the conflict in Stalingrad as rattenkreig—“rat war”—because so much of it concentrated on controlling holes, cellars, and sewers throughout the city. Military forces must be prepared to use a large amount of resources—in particular manpower as armored fighting vehicles and large equipment cannot be taken into subterranean systems easily—and specific training must be conducted on how to fight in these tightly confined, dangerous spaces to boost soldiers’ confidence and proficiency.

Snipers are a force multiplier and as an enabler must be given to tactical maneuver units. Soviet snipers proved devastating to German forces due to their ability to hide in a seemingly endless number of locations and put effective fire on hundreds if not thousands of critical targets. Conversely, when dealing with a high sniper threat, military forces must have proactive contingency plans to effectively counter snipers. The use of counter-sniper teams; particular weapons systems such as a tanks, antitank platforms, and armored personnel carriers that are solely tasked to quickly engage and destroy enemy snipers; the use of smoke; and moving forces through the insides of buildings were among the solutions.

The overarching lesson for military forces is that adaptability and improvisation of existing systems becomes critical. For example, the Germans had several types of tracked antitank guns that were very useful in Stalingrad, where rubble and partially knocked-down walls provided them with cover up to their hulls. Deployed in hull defilade behind infantry the weapons proved highly effective.

Conclusion

The carnage, intensity, and scale of the Battle of Stalingrad made it one of the most memorable and referenced urban combat events in history. The battle has become largely synonymous with modern conceptions of high-intensity urban combat. Its lessons for today’s military forces are important, but they should be tempered with facts about what really happened as well as the vast amount of on-the-ground adaptations that were required by the two forces that fought in it.

John Spencer is chair of urban warfare studies at the Modern War Institute, codirector of MWI’s Urban Warfare Project, and host of the Urban Warfare Project Podcast. He previously served as a fellow with the chief of staff of the Army’s Strategic Studies Group. He served twenty-five years as an infantry soldier, which included two combat tours in Iraq.

Major Jayson Geroux is an infantry officer with The Royal Canadian Regiment and currently a member of the directing staff at the Canadian Armed Forces’ Combat Training Centre’s Tactics School. He has been involved in urban operations training for almost two decades and is the school’s urban operations subject matter expert and urban warfare historian, having participated in, planned, executed, and intensively instructed on urban operations for the past seven years. He has served twenty-six years in the Canadian Armed Forces, which included operational tours to the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia-Herzegovina) and Afghanistan.

A special thanks to Modern War Institute intern Harshana Ghoorhoo, whose initial research and framework of this and following case studies set the conditions for success.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or that of any organization with which the authors are affiliated, including the Canadian Department of National Defence, the Canadian Armed Forces, and the Canadian Combat Training Centre and its Tactics School.

I recently saw the film Dredd on Netflix. The film was an interesting speculative scenario of urban and close quarters combat. The setting was an extreme built environment where the "judges" had to survive in a low intensity war situation and with non state actors.

The USSR had no initial plans to defend Stalingrad; it is not true that it was a prestige issue. Hitler divinding his curves, instead of concentrating them to take the Caucasus oilfields, however gave the Red Army the opportunity to defeat Paulus at Stalingrad and compel the evacuation of Army Group B, no matter how far out got towards Grozny. Which is what it did.

Forces, not curves.