War is hard. Even the sharpest mind can’t accurately predict or adequately prepare for trial by combat. It is inherently dependent on the enemy’s zags and the environment’s zigs—we can’t foresee where war will take us, so while we may shape it at the margins, we can never truly control the next stage of conflict. Moreover, even if we could predict where war might go, it wouldn’t really matter since we can’t replicate the precise conditions of war, and therefore we’ll never be fully ready for such violent challenges. Both characteristics bear heavily on what strategists can accomplish at war, and so these merit some scrutiny.

We cannot predict war accurately.

We cannot understand a field of study until it has a defined and understood unit of analysis, author and doctor Siddhartha Mukherjee pointed out in a recent CNN interview. Physics has the atom, computer science has the bit, and biology now has the gene. This extends to other areas: historians study past events, international relations scholars study states, and lawyers study case law. For strategists, the fundamental unit of war is two people fighting for a political purpose, what Carl von Clausewitz called the duel. (See chapter one of On War for more detail.) This atomic level of war exists at the tactical and the strategic level. “War is nothing but a duel on a larger scale,” Clausewitz wrote. Unfortunately for strategists, this irreducible minimum interaction is intrinsically multidisciplinary and simultaneously touched by so many other fields (e.g., psychology, sociology, history, law, philosophy, etc.) that scholars will never get their arms or heads around war as a whole. And since we won’t know what animates each conflict—why some soldiers and statesmen choose to fight and others don’t—we won’t be able to identify the trend lines well enough to work out where war will take us next.

We cannot prepare for war adequately.

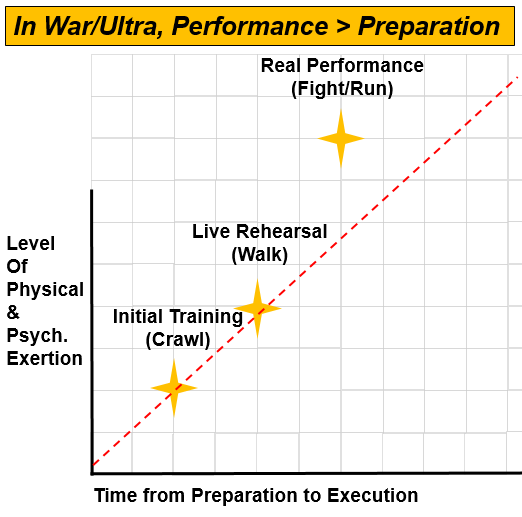

War is like ultra-distance running (i.e., any footrace beyond the marathon). The competitors physically jostle one another for advantage, amidst environmental conditions that impact all participants, to achieve some desired state (i.e., some just want to finish or “survive,” while others want to win, dominantly). War and ultras are often unequal parts slaying the environment, beating an opponent, and achieving some end.

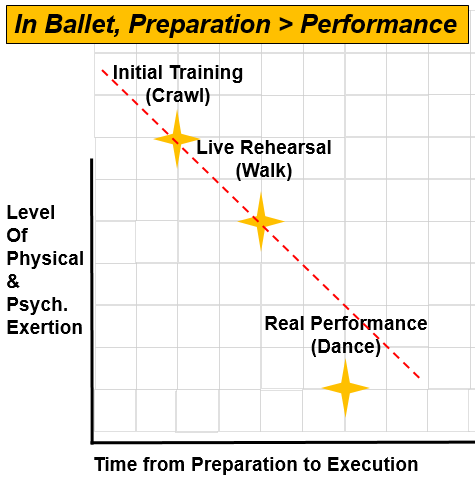

Recently, my wife and I ran an ultra in Moab, Utah. It was a first time at a longer distance for her. She’s transitioning from a career in ballet—she retired a few years ago as a principal dancer with the San Francisco Ballet, one of America’s top-tier companies. Her experience in ballet has always been to train for certainty, to spend days and hours preparing to execute minutes and seconds on stage. In dance, preparation always exceeds the requirements of performance—this was to train for perfection.

For her and other dancers, the move to ultra-running is difficult because the relationship between training and execution is flipped. In ultras, as in war, you always perform physically and psychologically beyond the bounds of your preparation: we can’t go out and regularly run twenty-five or fifty miles to prep for a fifty-kilometer race or hundred-mile run; and we certainly can’t train for Sgt. Jones to die. While preparation can help, one can never be said to be entirely “prepared,” and in this way, war is an act of faith—a belief in performance beyond preparation.

These twin reasons are why we cannot accurately predict war’s direction and we cannot adequately prepare for war’s challenge—and so we cannot control war. The best a strategist can expect is to influence and shape war by heeding the limitations imposed by humanity’s internal conditions and those imposed externally (i.e., demographics, geography, physics, etc.). In other words, a sense of strategic modesty is in order.

Image credit: Sgt. Michael J. MacLeod, US Army