The Art of War is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can, and then move on.

— General Ulysses S. Grant

With the perspective of more than one hundred years of history, U.S. Grant was much more than the commanding general of the US Army at the end of the Civil War and later president of the United States. Those who have read his memoirs know that he deeply understood the nature of war and the ability, as the quote above shows, to distill the essence of warfare into simple plans and orders. Through his use of distributed operations, theater-wide logistics, and what today we call “mission command,” he is considered to be the American military’s first operational artist. Importantly, throughout the Civil War, Grant also maximized the cooperation of the Army and the Navy at tactical, operational, and strategic levels, most notably during the Vicksburg campaign and the campaigns of 1864. Of the former, he noted, “the cooperation of the Navy was absolutely essential to the success (even to the contemplation) of such an exercise.” That cooperation between the land and sea domains was so important to him that as the theater-level commander at Vicksburg, he had himself rowed out to Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter’s flagship in the Mississippi for coordination.

Today, the cooperation and coordination of efforts in and between domains extends beyond land and sea to include air, space, and cyber—for a total of five domains. Each of the US armed services has an initiative aimed at what is generally termed “multi-domain operations.” The Army’s concept—originally labeled Multi-Domain Battle (MDB), though subsequently renamed Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)— stresses operations in time and space within, through, and across all five domains. Today’s Air Force approach also takes the MDO name, focusing primarily on the integration of operations in the air, space, and cyber domains. An emerging Navy concept is Distributed Lethality, an extension of its distributed operations and one employing cross-domain capabilities. The Marine Corps calls their initiative Expeditionary Advance Base Operations (EABO). The Marines of course have traditionally integrated air, land, and sea operations and EABO continues that tradition. The relevant joint concept is the Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Force 2020. The joint concept emphasizes cross-domain synergy, in which integrated operations between multiple domains are complementary, rather than just additive. Each of the service and joint concepts for multi-domain operations has as a major component the necessity for effective command and control within, though, and between domains. But what implications will multi-domain operations have on future joint and service command and control—and especially on mission command?

Grant’s description of the art of war is particularly applicable today, given the complexity of military operations; the contested nature of physical, virtual, and electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) battlespaces; and the accelerating emergence of technologies that enable operations within, between, and across all five domains. His Find out where your enemy is encompasses the range of joint command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (JC4ISR) functions and requires commanders and staffs to see, understand, visualize, and describe operational environments and threats across all domains in an integrated manner in support of decisions and action. Grant’s Get at him as soon as you can requires commanders and staffs to simultaneously integrate, synchronize, and distribute the deployment and employment of units and capabilities at local, regional, and strategic distances across, between, and within all five domains. Strike him as hard as you can requires commanders and staffs to attack with forces and to deliver physical, virtual, and psychological effects throughout theaters of war, joint operational areas, and during battles and engagements with powerful, distributed, multi-domain blows to secure the initiative, present enemies with more dilemmas than they can overcome, and destroy or defeat enemy forces to secure campaign objectives. Finally, and then move on suggests not only the mindset and ability to exploit advantage, but also to employ mobility, sustainment, and other capabilities to protect the force from enemy attack or effects within and across all five domains. Each of these major multi-domain functions—JC4ISR, maneuver, attack and protection—is enabled through multi-domain logistics, but primarily through effective command and control.

Imperatives of Multi-Domain Command and Control

“Find Out Where Your Enemy is”: Multi-Domain Intelligence and Knowledge Management

Knowing the enemy is necessary to succeed in any campaign or major operation. Today’s strategic, operational, and tactical environments, and emerging threats make knowing the enemy extremely challenging. A comprehensive, multi-domain view of the enemy is required both to understand the enemy before operations commence and to anticipate, see, and assess enemy operations as they unfold. This requires shifting from the current intelligence doctrine of all-source intelligence, which is driven by the collection “INTs” (SIGINT, HUMINT, ELINT, COMINT, etc.) to a doctrine of “all-domain intelligence,” driven by the necessity to see and understand equally well in all five domains. Recognizing that intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) is optimized for each domain, the burden falls on the staff to integrate intelligence analysis, visualization, and understanding across the domains. Moreover, such all-domain intelligence must yield a multi-domain common operating picture in support of planning, coordination, execution, and assessment.

The volume and velocity of data acquisition, information transfer, analysis, decision making, and assessment will be greater now than at any point in military history and will increase each day. Knowledge management must be maximized within, between, and across all domains, all echelons, and all physical and virtual battlespaces. Such management must therefore streamline the flow of information and intelligence, and then ensure commanders and staffs can digest the volume and availability of so much information. Capabilities and networks must be protected and enabled in cyberspace and the EMS and must be able to effectively support critical decision making when degraded by enemy action. This is not a critique of existing knowledge management systems and capabilities, but a recognition that new multi-domain integration requirements have emerged.

Knowledge management has always consisted of three components: people, technologies, and processes. Therefore, solutions for intelligence and knowledge management must enhance multi-domain leader and staff development, provide the technologies necessary to integrate across domains, and adapt processes in the direction of joint, multi-domain integration. As an element of the technology component, the Department of Defense is seeking capabilities like an Integrated Dashboard for Cyber Warfare, which would enable coordinating cyber effects with those of the other four domains.

“Get at Him as Soon as You Can”: Secure Multi-Domain Access

Each combatant command, joint task force, and service component must be able to access every domain. Access means the ability to see into, move combat power through, engage into, and defend from each domain. Access is always going to be competitive, whether in pre-conflict shaping and maneuvering for positions of advantage, or during conflict as each opponent seeks superiority in each domain while attempting to degrade or deny opponent operations in those same domains. Access also means developing the capability to deploy and employ systems not only across domains, but extra-regionally and through echelons, so that maximum use is made of all available resources. Access yields freedom of action and initiative, and it broadens the range of options and decisions available to the commander.

Access also means overcoming the enemy’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) strategies and capabilities. Enemy A2/AD is increasingly multi-domain, with land-based missiles and rockets exercising sea control, while terrestrial forces conduct physical and cyber anti-satellite attacks to deny access to space-based capabilities to US forces. Multi-domain access, then, is a competition for both domain control and the ability to attack one domain from another. In this regard, defeating enemy multi-domain command and control is critical to success.

“Strike Him as Hard as You Can”: Operationalize Kill Networks and Leverage Autonomous Systems

Multi-domain operations are networked, systemic operations in which the command-and-control networks exist and operate within and between domains and are immersed within broader military, governmental, information, and human systems. Such complex networks and systems suggest that the concept of “kill chains” no longer represents the reality of decide, detect, deliver, assess and must be replaced by a “kill network” approach that exploits networked sensors, shooters, and decision makers to meet the demands of collaborative cross-domain operations. In this case, kill chains are linear and largely single-domain sequences optimized to attack and neutralize known targets, whereas kill networks are non-linear, cross-domain, and are optimized to neutralize enemy capabilities as they emerge. A kill-network approach requires adapting doctrine, training, leader development, technologies, and organizations to effectively execute in future operations.

Perhaps nowhere is the potential of the application of the art and science of warfare more evident than in the employment of increasingly autonomous systems in multi-domain operations. Technologies have advanced to the point that commanders and staffs must command, control, and manage four sets of systems, determined by the degree of human control required over those systems. Most familiar to the military are the manned systems that have proliferated across military forces throughout history, including everything from a rifle to a fighter jet to an aircraft carrier. Increasingly during the last several decades, so-called smart weapons have emerged that are man-in-the-loop, such as a laser-guided missile, bomb, or artillery round. More recently man-on-the-loop systems have emerged, in which operations are largely autonomous once initiated; the Aegis air/missile defense system is an example of a man-on-the-loop system. Emerging are those systems that once initiated, operate entirely autonomously. Command, control, and management of this range of systems distributed across and acting in multiple domains simultaneously, for a variety of purposes and with different points or units of origin, will be a significant challenge. For example, the Navy is experimenting with combinations of unmanned, autonomous vessels to defeat enemy multi-domain A2/AD threats. An early finding from such experimentation is the necessity to train naval officers to manage both their manned and unmanned systems simultaneously.

“And Then Move On”: Multi-Domain Survivability and Resilience

Just as the United States is expanding multi-domain capabilities, potential opponents are doing the same. Thus, the threats to US forces are expanding, demanding innovative approaches to protect the force. For example, the Marine Corps is experimenting with placing traditionally land-employed artillery and air defense systems on Navy amphibious shipping, employing a multi-domain counter to a multi-domain threat.

Given that friendly forces are likely to operate distributed across each domain, the non-physical domains of cyber and the EMS could be the most contested of all the domains. Survivability of forces demands that command and control be exercised even when the EMS is degraded or denied. Every military organization, regardless of service or primary domain must learn and practice new and emerging cyber and EMS doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures, and must be able to anticipate, withstand, recover, and evolve in step with enemy cyber and EMS operations.

Challenges to Effective Multi-Domain Command and Control

Command and control is challenged by time and tempo. The physics of each domain produces different tempos of operations. While land operations are continuous, air operations are cyclic, as evidenced by the 72-hour air tasking order. Naval operations are conducted in pulses, driven largely by the logistics of naval engagements. A ship, even an aircraft carrier, fires all its onboard munitions in a few hours or days—a pulse of operations—and then must move to a secure location, often a port, to resupply. Space operations are either continuous or episodic, depending on a satellite’s orbital altitude and positioning. Cyber operations generally take long periods to develop and then occur in bursts. These differing tempos significantly challenge planning, coordinating, and executing multi-domain operations.

Command and control is also hampered by dissimilar command-and-control constructs. The Navy/Marine Corps Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment concept notes that Navy and Marine forces require a common tactical command-and-control doctrine for operations in a contested environment. Similarly, the Army’s mission command construct differs significantly from the Air Force’s centralized control/decentralized execution, even when both employ manned, armed attack aircraft to support land combat.

In the emerging operational environment, delivering effects in all five domains requires cyber and spectrum superiority. The American military and all potential opponents compete for superiority in cyberspace and the EMS and to deny their opponents the use of those domains. This competition is ongoing and will affect the start point for conflict operations in other domains. Perceptions of operational domains as discrete will be a liability in future conflicts; instead, the United States requires multi-domain operational concepts that exploit the evolving synergies between the domains.

The speed and complexity of multi-domain operations can outpace forces’ ability to effectively command, control, and integrate domain-specific forces. For example, in the initial stages of Operation Iraqi Freedom, the pace and complexity of operations frustrated coalition forces’ ability to integrate air and land operations. Further, rapid increases in computing power, software capabilities, data mining, and artificial intelligence are driving the US armed forces toward the requirement for incredibly fast decision making. Component and joint command-and-control structures, processes, and battle rhythms do not support such fast decision making.

Another challenge is that, thus far, the least contested domain has been space. The United States has increasingly relied on space-based capabilities to support military operations, specifically command and control. Space assets provide global communications; navigation, positioning, and timing necessary for precision strike; and enhanced ISR. China and Russia reportedly have conducted multiple, successful anti-satellite missile tests, so it is by no means a sure thing that in future large-scale conflicts, the United States will retain the same level of space-based capabilities in support of command and control, or more broadly joint command, control, communications, computers, and ISR.

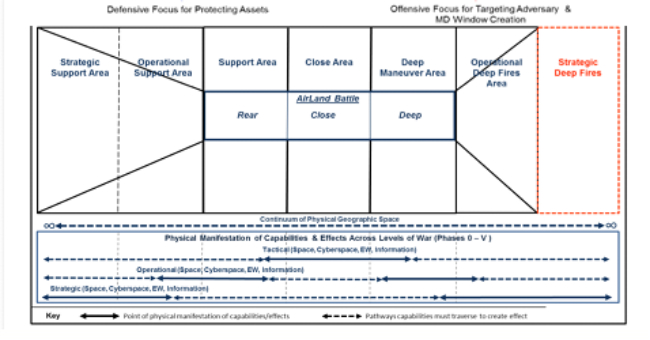

As campaigns and operations are planned, coordinated, and executed seams will emerge between domains. Those seams may be physical or virtual, and could create gaps that enemies could exploit. An approach to reducing the risk of seams is a common battlefield framework, similar to what the Army and Air Force employed in past AirLand Battle doctrine. Recently the Army and Air Force have jointly developed a common, expanded Multi-Domain Battlefield Framework. To date, the other services have not been integrated into the effort.

Potential opponents—including Russia, China, Iran, or North Korea—are rapidly developing capabilities to threaten American JC4ISR in cyberspace and the EMS. Such threats could create an operational environment in which that JC4ISR is limited or denied either geographically or functionally. That compels American commanders, staffs, and organizations to develop capabilities to fight in the “electronic night,” largely without the sensors and communications networks that we have relied on for so long. The increasing use of autonomous and semi-autonomous systems (man-in-the-loop/man-on-the-loop) increases risk if enemy forces secure superiority or control of the EMS, and if US electronic-warfare capabilities are not improved.

Decentralized vs. Centralized Operations

The debate over decentralized versus centralized command and control is as old as military history itself. Most often today, decentralized operations are characterized as mission command, in which subordinate leaders are empowered to make local decisions within a senior commander’s intent. Retired Gen. Martin Dempsey defined mission command as “the conduct of military operations through decentralized execution based upon mission-type orders.” The requirement to engage in operations across domains, and therefore in other services’ traditional battlespaces, creates new considerations and tensions between centralized and decentralized control and between traditional command and control and the newer mission command.

For decades, US Navy operations have increasingly been pulled under centralized control, with all the elements of a carrier battle group controlled by the carrier. However, the concept of distributed lethality recognizes the need for more dispersed operations, the likelihood of significant threats in the EMS environment that will frustrate communications and data distribution, and the criticality of rapid decision making to take advantage of opportunities or secure the initiative. Distributed lethality indicates that increasingly individual ship commanders, even while operating as part of a dispersed battle group, will need more freedom to make tactical decisions and exercise mission command.

While the Navy has been considering increased decentralization, the Air Force is moving in the opposite direction. Recent Air Force experimentation has examined Multi-Domain Command and Control (MDCC), a system that would integrate, and therefore control, all air, space, and cyber operations into a single integrated tasking order to replace the current air tasking order. Such an approach could reduce flexibility in multi-service, cross-domain operations, leading to a single point of failure, thereby making more of the joint force and its operations vulnerable to cyber and EMS threats. This is clearly an area where further joint experimentation and wargames will be necessary to understand the risks.

Air Force MDCC experimentation also suggests the need for a single Joint Warfighting Command with global reach. Recognizing how difficult it can be for combatant commands to maintain global awareness and to know and access capabilities in other regions, and their lack of authority for extra-regional operations, the Joint Warfighting Command would centralize control into a single headquarters without such deficiencies. Still, the Air Force does recognize that a contested EMS could risk traditional and preferred centralized control/decentralized execution, and could force a distributed control approach. The Navy too has a joint command approach: its Composite Warfare Commander concept applies to joint, and therefore multi-domain, Navy and Marine Corps operations.

Increasing layers of command-and-control technologies, networking, and smart weapons might drive operations toward centralized rather than decentralized control. The search for efficiencies in technological investments might inhibit individual commanders from exercising all their weapons systems and might restrict command initiative. In fact, naval experimentation has suggested that dispersed operations in contested EMS environments improve carrier survivability, but lengthen decision cycles, thus increasing the institutional tension between centralized and decentralized operations. At the same time, the proliferation of sensors, communications, and smart weapons are accelerating the pace of operations and are fundamentally changing commanders’ and staffs’ perception of time, timing, and opportunity. The ubiquitous capabilities, coupled with this time compression, could hinder expressing a commander’s intent and could slow initiative.

Toward a Multi-Domain Culture

Gen. Bob Brown, commander of US Army Pacific, states that the services can no longer concentrate solely on their domains. To succeed, all services must better integrate planning, operations, command and control, and effects across all domains. To achieve that, he suggests, requires a new mindset. All forces must change their distinct service cultures to a new culture of inclusion and openness, focusing on a “joint first” mentality. For the Army, he further suggests integrating a mission-command mindset, where every person is empowered to seize the initiative based on his or her role or function.

Integrated operations across multiple domains means cooperative operations that employ forces and capabilities from more than one service. To achieve the required level of service cooperation in a multi-domain operation, the foundation must be mutual trust. No service fights alone, yet they often think and plan individually. Such thinking, which envisions “lanes and stovepipes,” will not be effective and places US forces at risk. As retired Gen. Dave Perkins, former commanding general of US Army Training and Doctrine Command, stated, “We have to get away from the idea of domain ownership, of how do I own this domain, where do I put up the stakes, if you come into my domain you have to clear it with me, etc.” His point was that no one owns a domain, because everyone has to use them; commanders have to maneuver not only in “their” domain, but also through others.

Cultural challenges to the command and control of multi-domain operations are driven, to a significant degree, by service biases: each service is biased toward its role and contribution to the success of campaigns, battles, and other military operations; each service also has a view to how it is best employed. For example, major air and ground commanders have disagreed on the proper employment of airpower in a campaign. Service bias and culture exist in each service-specific multi-domain concept, particularly with regard to the degree of control exerted over the service’s primary domain and other domain forces.

Leader Development for Multi-Domain Operations

Effective multi-domain operations will require leaders who sense, learn, think, plan, decide, assess, and lead differently. The complexity of an enemy’s operational environments, hybrid strategies, and asymmetric operations requires leaders to move away from traditional service- and domain-oriented patterns of thought, and to adopt more non-linear approaches to operations and problem solving. Moreover, leader development must draw together current and future leaders because multi-domain unity of effort will require unity of thought. More joint schooling and more joint operational assignments will lead to a multi-domain mindset. Moreover, multi-domain operations will require leaders with mental agility, who can rapidly and simultaneously “multi-task” across multiple echelons, domains, functions, and operations.

Leaders also can no longer simply be experts in their own domain. A barrier to leading multi-domain operations is a weak understanding of maneuver in domains other than that of the leader’s primary service. Increasingly earlier in their careers, leaders must understand the capabilities, forms of maneuver, and operations in all domains, and need to develop an appreciation for multi-domain maneuver. Such leader development may take the form of joint wargames and exercises, professional military education, self-study, or preferably a combination of all three. Whereas today joint—in other words, cross-domain—education occurs at the Intermediate Military Education level (major/lieutenant commander), such education will have to be conducted at lower levels in the future.

The command-and-control challenges to effective multi-domain operations are not limited to, or even primarily, those of technology. While technological capabilities to conduct and to direct multi-domain operations are significant, it is the non-technological challenges that must be met. These include exercising both the art of command and the science of control, finding the balance between decentralized mission command and more centralized control, inculcating a DoD-wide culture of collaborative command to achieve cross-domain synergy, and developing leaders with multi-domain knowledge and a desire to achieve unity of thought and action across all domains.

The implications for command and control from multi-domain operations truly run the gamut of doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership and education, personnel, and facilities. Emerging concepts from the services must coalesce into a new joint doctrine. Organizational initiatives such as the Navy’s distributed Surface Action Group and the Army’s Multi-Domain Task Force must be experimented with to find the right mix of units and capabilities. More joint training must occur at multiple echelons to build multi-echelon readiness. Materiel solutions must both enable and protect operations in and between each of the five domains. Leader development must shift from being service-centric to progressively joint-centric as leaders progress through the ranks. Personnel of all ranks and military occupational specialties must be able to articulate their role in the multi-domain fight; facilities and infrastructure must support global, multi-domain operations, and most importantly, multi-domain command and control. The promise of multi-domain operations can be only be realized through a multi-domain mission-command approach that exercises both the art of command and the science of control.

Col. James K. Greer Jr., USA (Ret), wrote this essay while an Adjunct Research Staff Member in the Joint Advanced Warfighting Division of the Institute for Defense Analyses. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or any organization with which the author is affiliated.

Image: “Admiral Porter’s Fleet Running the Rebel Blockade of the Mississippi at Vicksburg, April 16th 1863.” (Source: US Naval Historical Center Photograph)