“In principle organization should be based on effective command in combat.”

— Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair in a January 1944 memorandum to General George C. Marshall

The US Army is undergoing a significant transformation. The Army of 2030 is conceptualized as a force optimized for new challenges and characterized by new capabilities. The multidomain operations operational concept shifts the service away from the contingency operations of Iraq and Afghanistan and toward large-scale combat operations. But an even more fundamental change, spanning and interacting with the full range of transformation—from technological to operational—is one of force design and structure. The Army is moving from the brigade-centric model adopted for the post-9/11 wars to a division-centric one. But what should those divisions actually look like?

While today’s operational environment presents different challenges, the Army has made similar adjustments before. During the Cold War, Army structure and design reflected a pendulum of national security policies and priorities. The Army oscillated between heavy, nuclear-capable forces to defeat Soviet armor in the Fulda Gap and light, rapidly deployable forces for contingencies along the periphery. As we shape the Army of tomorrow, it is important to reflect on the lessons of history.

Force design refers to the composition of a particular unit. Force structure refers to the number and type of units in the Army. The two have an interdependent relationship. Both are critically important to success on the battlefield and are constrained by budget and available manpower. For example, during World War II the Army designed smaller divisions so it could field the large force structure of eighty-nine divisions. Since then, an array of complex factors, both external and internal, combined to require the Army to adapt. A successful force design assigns commanders at echelon sufficient combat power to flexibly task organize within their span of control to conduct combined arms maneuver and defeat an adversary in combat.

Cold War national security policy was the most significant external factor that drove force design changes to US Army infantry divisions. Eisenhower’s New Look policy, Kennedy’s Flexible Response, the Nixon Doctrine, and the Reagan Doctrine all envisioned distinct roles for the Army. In combination with the cycles of conflict, these different policies caused Army budget and personnel fluctuations. Each policy attempted to forecast who the most likely enemy was, what type of combat operations would occur, when the next conflict was expected, where the fight was expected, and how the force would be employed according to the latest doctrine. More accurate national security policies increased the probability that the Army was structured and designed to properly meet the threat.

Technology evolved rapidly during the Cold War, bringing with it force design changes. Greater weapons ranges increased the breadth and depth of the battlefield. Motorization and longer radio communications ranges allowed units to operate at these increased distances, altering tactical and operational doctrine. The invention of the nuclear bomb and its availability in smaller weapons also had significant impacts on infantry division design. Improved weapons technology could eliminate the need for specialty units, as when the introduction of the bazooka made dedicated antitank gun units unnecessary. New weapons could also increase combat power or provide a capability that was worth stretching a commander’s span of control and adding sustainment costs, as helicopters did. New technology created both solutions and problems for force design planners.

During the Cold War, each new infantry division design attempted to balance internal factors for combat effectiveness, the most important being span of control, combat power, and mobility (with strategic mobility at odds with tactical mobility). To maximize combat power within a commander’s span of control, the Army used the principles of streamlining and pooling. Streamlining limited a unit to what it needed daily while pooling held occasionally used assets at higher echelons. Pooling assumed that a division would not operate independently. Higher echelons then attached pooled assets to subordinate units to create task forces designed to conduct specific missions within a commander’s span of control. With global responsibilities during the Cold War, planners often prioritized the ability to deploy by aircraft from the United States over firepower and tactical mobility on the battlefield.

The Army conducted nine major reorganization efforts during the Cold War: the reorganization of triangular divisions, 1947–1948; the pentomic division, 1955–1963; the Reorganization Objective Army Division (ROAD), 1960–1963; the 11th Air Assault Division (Test), 1963–1965; the 1st Cavalry Division triple capability, 1971–1974; the Division Restructuring Study (DRS), 1975–1979; Division 86, 1978–1980; the high-technology motorized division, 1980–1988; and the 7th Infantry Division (Light) 1983–1986. The four most significant of these offer particularly relevant lessons to the Army of today: the triangular division, the pentomic division, ROAD, and Division 86, which led to the Army of Excellence light division.

Combat lessons from World War II coupled with better weapons technology created a modified triangular division that fought the Korean War. President Eisenhower’s New Look policy called for the pentomic division to survive both a nuclear battlefield and budget cuts. ROAD adapted to President Kennedy’s Flexible Response policy by being capable of competing with communism anywhere on the spectrum of conflict, and it adjusted to meet the requirements of combat in Vietnam. After the Vietnam War, the less interventionist Nixon Doctrine and Division 86 refocused on conventional heavy divisions deterring Soviet aggression in Europe, although Cold War events created a requirement for light divisions. America’s undulating Cold War national security policy, personnel and budget constraints, and the need to incorporate technological improvements while balancing span of control, combat power, and mobility interacted to drive these changes to infantry division force design.

Triangular Division

Although used during the Spanish-American War, the US Army first formalized the triangular division in 1905 with the publication of Field Service Regulations, United States Army. The newly established Army General Staff departed from European and American military norms by making the division, instead of the corps, the basic unit for combining arms. The 1910 Field Service Regulations, United States Army codified division end strength for the first time and called for a division of 19,850 soldiers. However, in preparation for the trench warfare on the Western Front, the Army organized into 28,000-man square divisions in 1917, maximizing firepower at the cost of mobility. After the war, General John J. Pershing advocated for a more mobile three-unit system. Budget cuts delayed modernization efforts until the 1930s, at which point other countries were experimenting with motorized and armored divisions.

After testing in 1937 and 1939, Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall approved the new triangular division, which was designed to be more mobile and flexible than the previous square division. Being half the size, the triangular division required less road space and transitioned faster from movement to battle formation. It was also more flexible since it eliminated the fourth regiment, seen as an excessive reserve, and its smaller size allowed corps to maintain a division in reserve. The name was derived from the elimination of two brigade headquarters and one infantry regiment from the division, leaving three infantry regiments. The approved variant eliminated artillery regiments in favor of four battalions, three of 105-millimeter artillery and one of 155-millimeter. This allowed the division to create regimental combat teams by attaching field artillery battalions to each infantry regiment. After streamlining the division by pooling support units at higher echelons, the triangular division strength at the start of World War II was 11,485 soldiers.

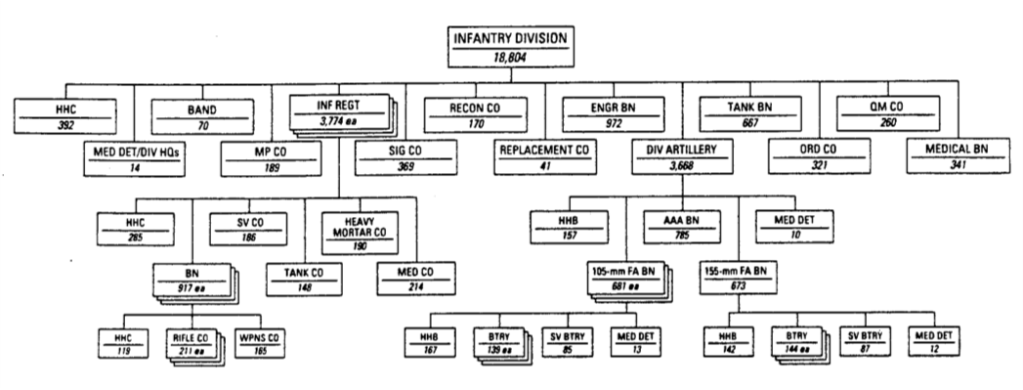

During World War II, division and corps commanders believed the triangular division was too streamlined and lacked important capabilities. The 1948 reorganization added an organic tank battalion and antiaircraft artillery battalion to the division as well as an organic tank company for each infantry regiment. This codified what were habitually attached capabilities from higher headquarters during World War II. It also added more engineers, military police, maintenance, quartermaster, communications, intelligence, reconnaissance, and administrative soldiers seen as necessary to operate on the larger battlefields created by motorized formations. Artillery batteries increased from four guns to six, increasing the division’s artillery firepower by 50 percent without increasing overhead staffs. These additions resulted in an end strength of 18,804. Planners made these changes based on lessons learned from combat.

In 1950, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea unexpectedly invaded the Republic of Korea. To maintain the number of overall divisions with postwar budget cuts, the Army had left divisions undermanned, which created a hollow Army. General Douglas MacArthur “almost totally gutted” the 7th Infantry Division in order to bring his other three divisions up to strength for combat in Korea. US divisions relied on Korean Augmentation to the United States Army (KATUSA) soldiers to become fully manned. The divisions received new weapons technology that increased firepower including the 105-millimeter recoilless rifle, a larger 3.5-inch bazooka, new 81-millimeter and 4.2-inch mortars, along with more automatic rifles. The new bazooka removed the need for dedicated antitank units, and its increased firepower was necessary to penetrate Soviet-built T-34 tanks. The Korean War also saw the combat debut of the helicopter. Infantry divisions were each authorized ten helicopters for supply and medical evacuation. The Army chief of staff estimated that the updated triangular division achieved 68 percent more firepower with only a 20 percent increase in personnel.

Pentomic Division

President Dwight Eisenhower’s New Look policy sought to deter the Soviet threat, cut taxes, and balance the budget. To meet the Soviet threat to US security, it relied on “the capability of inflicting massive retaliatory damage” delivered through the Strategic Air Command as a more cost-efficient method than maintaining a large standing army. The Army’s budget was cut from $15 billion in 1953 to $7.5 billion in 1957. To maintain the force structure of twenty divisions, the Army reduced division force design by 760 soldiers and undermanned divisions in the continental United States by 2,700 soldiers each. The cuts weren’t enough, and the number of divisions dropped from twenty to fourteen.

Army Chief of Staff General Maxwell Taylor embarked upon a restructuring to keep the Army relevant within the New Look policy, protect its budget, and fight on a nuclear battlefield. The Army found the solution in tactical nuclear weapons. The Army War College began a study in 1954 that produced what would become the pentomic division. It was small, with only 8,600 soldiers, and almost completely air transportable. The design cut from the division all armor, antiaircraft, engineer, and reconnaissance units, in addition to most logistical and administrative personnel. It replaced all division types: infantry, airborne, and armored. The armor, artillery, and engineering communities all objected to the design, and the Command and General Staff College did not believe the new division had the mass necessary for combat.

The pentomic division derived its name from the five subordinate battle groups that replaced the old brigades, regiments, and battalions. Fewer intermediary headquarters meant faster orders processing time from division to company. A colonel commanded each of the battle groups of 1,427 soldiers that were composed of five infantry companies. To reduce span of control issues in the battle group’s headquarters company the radar section, reconnaissance platoon, heavy mortar platoon, and assault weapons platoon formed a separate combat support company. These assets allowed the battle group to conduct combined arms operations organically. The doctrine was to mass quickly for combat and then disperse to avoid presenting a target large enough to elicit an enemy tactical nuclear strike. The small amount of division artillery had tactical nuclear capability with an Honest John rocket battery and an 8-inch howitzer battery. To increase strategic mobility at the cost of combat power, planners chose the airmobile 105-millimeter over the more powerful 155-millimeter howitzer.

Although General Taylor supported the pentomic division, it was not popular. The testing of the pentomic division revealed strengths in flexibility, unity of command, mobility, and nuclear firepower. However, the structure was deficient in ground surveillance, artillery support, staff organization, and the ability to conduct sustained combat operations. The airlift capability forced compromises that reduced the division’s combat power. Radio technology was not sufficient to allow division and battle group commanders to maintain their span of control over the widely dispersed units. “Every time I think of the . . . Pentomic Division I shudder,” said General Paul Freeman, former commander of Continental Army Command . “Thank God we never had to go to war with it.”

Reorganization Objective Army Division

The pentomic division did not meet the requirements of President John F. Kennedy’s Flexible Response policy. In February 1961, shortly after Kennedy took office, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara sent the president a letter proposing changes to the military budget: “In concentrating on nuclear war, we have in recent years neglected our ability to wage non-nuclear war and have severely limited our range of policy choices. . . . In sum, the primary mission of our overseas forces should be made non-nuclear warfare.” After an examination, McNamara concluded that the US military had been successful in deterring an “overt attack” from the Soviets but was “neither organized nor oriented for the task of meeting and counteracting” the Soviet strategy of indirect aggression. Kennedy supported a $100 million plan for Army procurement and reorganization. With additional funding, Kennedy directed the Army to improve tactical mobility, increase nonnuclear firepower, and modernize its divisions in Europe.

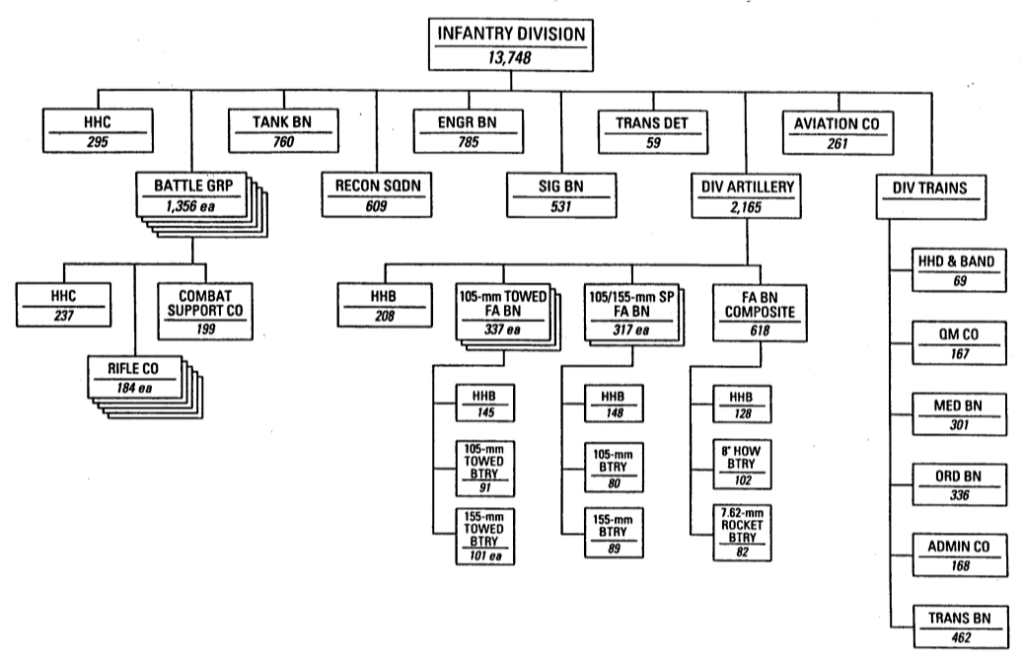

The new Reorganization Objective Army Division (ROAD) initiative envisioned an infantry division designed to operate against heavy conventional Soviet forces in Europe or against communist insurgents on the periphery. Infantry, mechanized infantry, and armored division designs were standardized. Infantry divisions had eight mechanized and two tank battalions, mechanized divisions had seven mechanized and three tank battalions, and armored divisions had five mechanized and six tank battalions. The division consisted of “a military police company; aviation, engineer, and signal battalions; a reconnaissance squadron with an air and three ground troops; division artillery; and a support command.” The division operated from three command posts and had two assistant commanders to expand the division commander’s span of control. The division support command was a new concept that also helped increase the division commander’s span of control by delegating supply, maintenance, medical services, and rear area security responsibilities to the support commander.

The design was largely a return to the triangular division except ROAD divisions labeled their subordinate units brigades instead of regiments. Battalions were largely unchanged from their configuration in the later stages of the triangular divisions with a headquarters company, three line companies, and a headquarters and service company. Two new weapons added to the battalion were Davy Crockett low-yield nuclear recoilless guns and antitank missiles. Like combat commands from armored divisions in World War II, brigades were only responsible for directing combat operations of standardized, self-sufficient battalions. The battalions received administrative support directly from the division. Ironically, there were more battalions than previous battle groups, which increased flexibility and survivability on a nuclear battlefield. Despite their greater number, these battalions were easier to control due to the addition of the brigade echelon.

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 and the threat of an imminent war in Europe put the transition to ROAD on hold. In a summit in Vienna, Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev met for the first time. Khrushchev gave Kennedy an ultimatum that if Soviet demands for a withdrawal of all armed forces from Berlin were not met, access to West Berlin would expire at the end of the year. On 24 July, President Kennedy authorized an immediate strengthening of conventional US Army forces in Europe under the existing pentomic division structure. The plan was to fully man and equip the five US divisions in Europe and add one thousand soldiers each to the three divisions in the United States so they would be combat ready by December. Supplemented by NATO troops, the goal was to be able to stop a Soviet conventional attack by the end of the year.

Kennedy announced his six-step plan the next day: “To fill out our present Army Divisions, and to make more men available for prompt deployment, I am requesting an increase in the Army’s total authorized strength from 875,000 to approximately 1 million men.” On August 13, the Soviets began constructing the Berlin Wall. Fortunately, the Berlin Crisis did not turn the Cold War hot, and the pentomic division was not tested in combat. In Kennedy’s words, “It’s not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.” During the crisis, production of the new M14 rifle, M60 machine gun, M60 tank, and M113 armored personnel carrier were expedited, which allowed for a faster transition to ROAD after the crisis. To shorten deployment timelines, the Army prepositioned equipment in Europe for one armored and one infantry division. This was an expensive workaround to increase strategic mobility.

The 1st Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions organized under ROAD in 1962 as a test, with the rest of the Army to follow. Tensions with the Soviets rose again and interrupted the transition, this time during the Cuban Missile Crisis. In October 1962, the newly restructured 1st Armored Division was assigned to an assault force to invade Cuba. The division moved from Fort Hood, Texas to Fort Stewart, Georgia where it trained to conduct amphibious operations. Again, the crisis passed without the outbreak of war and the 1st Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions began testing the ROAD design, where both performed well.

General George Decker, the Army chief of staff, reported to the secretary of the Army that “ROAD provides substantial improvements in command structure, organization flexibility, capability for sustained combat, tactical mobility (ground and air), balanced firepower (nuclear and nonnuclear), logistical support, and compatibility with Allied forces (particularly NATO).” The new structure had better reconnaissance due to the increased number of helicopters and twenty, as opposed to the previous twelve, cavalry platoons. With only a 2 percent increase to end strength, ROAD brought a significant increase to nuclear and conventional firepower. A drawback was that the twelve-channel very-high-frequency radio for the division headquarters was time-consuming to operate and its forty-five-foot antenna was too conspicuous. The new force design was only possible because the budget increased by $12 billion from 1961 to 1963, but the planned strength increases of thirty-one thousand troops during that period did not occur, leaving divisions stationed in the United States understrength.

In 1965, the ROAD divisions and the first airmobile division, the recently reorganized 1st Cavalry Division, experienced their baptism of fire in Vietnam. Air mobility capitalized on advances in helicopter technology, increasing the speed at which the Army could move troops across the battlefield. Air mobility and attack helicopters were especially useful with Vietnam’s limited road network. Most infantry units adapted to combat in Vietnam by adopting modified light infantry tables of organization. Select divisions received extra battalions to increase their combat power. Infantry battalions added a fourth rifle company for base defense. In terms of weapons systems, the Army adopted the M16 rifle and M72 light antitank weapon, which replaced the heavier 90-millimeter recoilless rifle, giving the infantry more mobile combat power. Better radio communications allowed units to call for substantial fire support from firebases, helicopters, and aircraft. After the 1st Cavalry Division proved that the 155-millimeter howitzer could move by helicopter, both airmobile divisions in Vietnam received an additional 155-millimeter battalion. The real-world challenges of war drove organic change as airmobile and infantry divisions adapted to the combat environment in Vietnam.

Division 86 and the Army of Excellence Light Division

In 1969, Richard Nixon became president, and America’s experience during the Vietnam War heavily influenced his defense policy. He instituted the less interventionist Nixon Doctrine, which promised that “the role of the United States as world policeman is likely to be limited in the future.” During and after the withdrawal from Vietnam, the Army experienced significant reduction to end strength from 1.5 million to 650,000 soldiers by 1972. Only twelve regular Army divisions remained. On the same day as the Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird announced the end of the draft. In 1968, 299,000 men were drafted, compared to only 50,000 in 1972. As the Army transitioned to the all-volunteer force, it also refocused planning on a conventional war against the Soviets in Europe. The 1973 Arab-Israeli War demonstrated the lethality of modern systems and helped spur the Army toward technological innovation to compensate for being outnumbered in the Fulda Gap.

In 1975, Army Chief of Staff General Fred Weyand was concerned that new technology resulted in “add ons” to the divisions without being properly integrated and called for a new force design. The recently created Army Training and Doctrine Command was tasked with conducting the Division Restructuring Study, which created a “heavy” division under the concept of active defense. Before testing was complete, General Donn Starry assumed command of Training and Doctrine Command. Starry stressed offensive capability and the ability to decisively mass effects of air and ground combat power against an opposing force. His ideas evolved into AirLand Battle, which Field Manual 100-5, Operations formalized as doctrine in 1982. AirLand Battle called for speed, flexibility, rapid decision-making, and deep attack. It was a nonlinear concept that further enlarged the battlefield and stressed maneuver.

Division 86 was developed around the concept of AirLand Battle, which focused on fast-paced, heavy fighting against Soviet forces in Europe. It was named Division 86 since the Army believe that 1986 was the furthest it could forecast the threat the division type was built to face. Theoretically, AirLand Battle would allow a smaller US Army with better-trained soldiers and leaders to defeat a larger Soviet force. “Division 86,” wrote one Army officer in a historical review of force structure and design, “was probably the most well orchestrated and thorough division design effort ever conducted.” With AirLand Battle established, designers knew how, where, and against whom the divisions would fight. The restructuring began with the concept of the heavy division.

Designing standardized light divisions proved more difficult, because there wasn’t a perceived requirement for limited contingencies under the Nixon Doctrine. Then the Soviets invaded Afghanistan and the Iran hostage crisis occurred, which created the perception that a flexible, rapidly deployable division was needed. The success of light forces in the Falklands War, the Lebanon War, and the invasion of Grenada proved their efficacy. Starry standardized infantry, airborne, and airmobile divisions into a light division concept that could be airlifted to fight “in contingency areas, such as the Asiatic rim” while still having the combat power to fight Soviet forces in Europe.

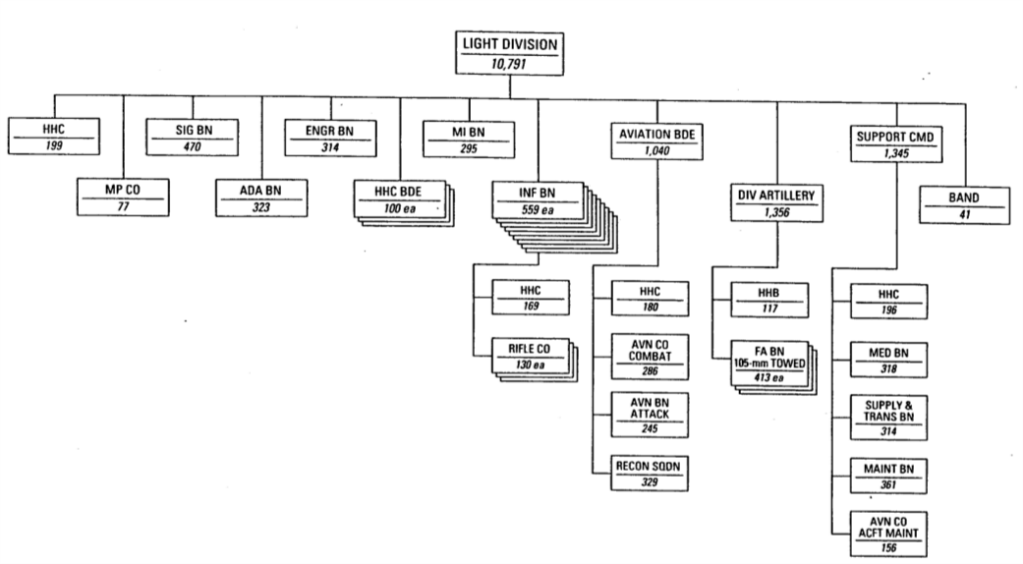

On January 18, 1984, President Ronald Reagan approved a 10,791-soldier-strong light division. Completely air transportable, it consisted of a headquarters and headquarters company; a military police company; signal, air defense artillery, intelligence, and engineer battalions; nine infantry battalions; division artillery; three brigade headquarters; an aviation brigade; a support command; and a band. Division artillery consisted of three towed 105-millimeter howitzer battalions, and one battery of 155-millimeter howitzers. The attack aviation brigade contained an attack aviation battalion and a reconnaissance squadron. Each infantry battalion had three rifle companies and a headquarters company, which contained a dismounted reconnaissance platoon, an antiarmor platoon with four antitank missile launchers, and a heavy mortar platoon. The only vehicles present in the infantry battalions were high-mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles. When augmented and task organized appropriately, light infantry forces would be able to combine arms at brigade, battalion, and company levels.

Light divisions could operate in more restrictive terrain and were smaller, cheaper, and faster to deploy than heavy divisions, but the overall reorganization to create them was costly in personnel and money. Part of the new “Army of Excellence,” light divisions planned to rely on lightweight, high-technology weapons and highly trained “soldier power” to compensate for the lack of weight and numbers. The division was so light it could only operate for forty-eight hours in a low- or mid-intensity combat environment before requiring external support. In order to build the light divisions, the Army trimmed down the authorized size of heavy, air assault, and airborne divisions and also relied on roundout brigades from the Army Reserve and National Guard. The combination of heavy and light divisions proved effective during the First Gulf War.

The Army Division of Tomorrow

During the Cold War, Army planners nested infantry division force design within the swinging pendulum of Cold War national security policies. The Soviet Union provided a stable adversary to plan against. ROAD infantry divisions and light divisions were designed to compete with the global communist threat on the periphery, while pentomic divisions and Division 86 were optimized to defeat Soviet armored columns in the Fulda Gap. Infantry divisions had the challenging task of being light enough to strategically deploy via airlift but heavy enough to fight Soviet armor in Europe. Specific national security strategy and doctrine set the foundation for successful force design.

As the priorities of today’s Army swing back to division-centric, large-scale combat operations, there are multiple adversaries to plan against. The 2022 National Defense Strategy describes the People’s Republic of China as the pacing challenge, Russia as the acute threat, and North Korea, Iran, and violent extremist organizations as persistent threats. This diverse set of adversaries makes structuring and designing the Army difficult. Operating on widely dispersed islands across the Indo-Pacific has significantly different requirements than fighting in the Suwalki Gap. This is reflected in two of the new division types, light and armored (reinforced). However, in considering new division structures the Army should be careful not to overspecialize. The light division concept was ineffective in the Southwest Pacific during World War II, and motorized divisions were found to be impracticable in 1943 because of shipping constraints. This raises an important design question: Should an armored division (reinforced) be a separate division type, or would it give the corps commander more flexibility to pool the specific engineer assets assigned to it at the corps level?

During the Cold War, the Army exercised a combination of five options when faced with personnel constraints: reduce force design, reduce force structure, underfill units, rely on roundout units from the National Guard and Army Reserve, or rely on augmentation by allied and partner forces like in Korea. Understrength units during peacetime created low readiness levels and repeatedly led to a hollow Army. Leveraging roundout units also decreased readiness by increasing deployment timelines.

Today, the Army is reducing force design and force structure to avoid creating a hollow force while also building new capabilities. Infantry and Stryker brigade cavalry squadrons are being inactivated, infantry brigade weapons companies are being downsized to platoons, and security force assistant brigades are losing some of their positions as the Army seek to build multidomain task forces (MDTFs). Given the faster and more lethal character of war, dependence on roundout units means incurring more risk. The KATUSA program continues to this day. Given the pace of change, are prepositioned equipment sets still a suitable method of decreasing mobilization timelines?

Changes to force structure and design are expensive. Historically, successful changes have required political support to secure funding and the sponsorship of an influential general to gain institutional support from the Army for cultural change. Not only do MDTFs enable the Army to conduct multidomain operations, but they also maintain Army relevancy against the pacing challenge. Three of the five MDTFs have been assigned to the Indo-Pacific.

Throughout the Cold War, doctrine adapted to weapons and communications technology, pushing the echelon for combined arms maneuver downward. Weapon ranges and communication distances increased the breadth and depth of the battlefield. New systems increased combat power that compensated for mass lost by dispersion. Improved weapons technology, such as the bazooka or nuclear-capable 155-millimeter round, could eliminate the need for specialized units. Some innovations provided a capability that stretched a commander’s span of control and added support costs, such as long-range antitank missiles and the helicopter. Infantry divisions had an entire aviation brigade by the end of the Cold War. However, new systems increased the burden on battlefield commanders to integrate all their effects. In the case of the pentomic division, this overextended the commander’s span of control. To counteract this, ROAD added the brigade echelon, allocated deputies, and created division support commands to reduce the number of reporting units.

Since the end of the Cold War, weapons ranges have continued to increase, and tactical communications systems now have a global range. The concept of multidomain operations is different from AirLand Battle, but both spread the responsibility of combined arms maneuver across echelons. This prevents individual commanders from being overwhelmed by managing the more numerous, longer-range effects. For multidomain operations, this facilitates convergence, “the integration of capabilities in all domains” and across echelons. The Army has begun using artificial intelligence and passively tracking command-and-control systems such as the Tactical Assault Kit. Leveraging these systems, how much more combat power can an echelon effectively control in combat? Ultimately, the better the Army balances span of control, combat power, and mobility in its force design, within the never-static cycle of national security policy and amid personnel and budget constraints, the more likely it is to achieve operational success on the battlefields of tomorrow.

Major Max J. Meinert is an infantry officer currently transitioning to serve as an Army strategist. He holds a bachelor of science in military history from the United States Military Academy and a master of arts in public history from Villanova University. His assignments include the 82nd Airborne Division, US Army Europe G5, Special Operations Joint Task Force Afghanistan, 1-2 Stryker Brigade Combat Team, and I Corps Stryker Warfighters’ Forum.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Richard Hart, US Army