“Amateurs talk tactics, but professionals talk logistics.”

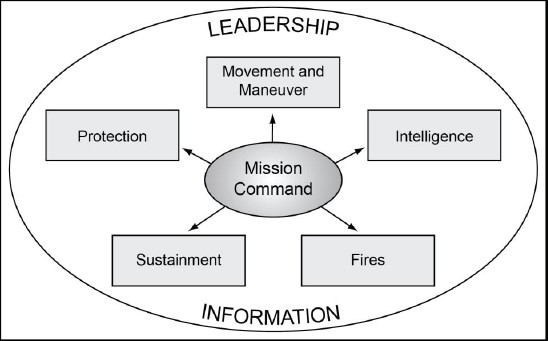

It’s a time-honored apocryphal quote, attributed to everyone from Napoleon Bonaparte to Omar Bradley. And it’s one that seems particularly appropriate in the context of the Army’s use of autonomous vehicles (AVs). While the potential of autonomous vehicles in some of the Army’s six warfighting functions—like intelligence, protection, and fires—at the tactical level is already proven, programs exploiting AVs’ potential for functions like sustainment and movement (particularly when it comes to ground transportation) are still in their infancy.

These programs will likely reach adolescence in the very near future, however. The Army has been experimenting with AVs through the Automated Ground Supply program for the last few years, and the commander of the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command recently announced a goal of replacing up to 40 percent of frontline troops with unmanned platforms. Progress by US competitors is also driving autonomous vehicle research. China, for example, is rushing into the AV market in order to position itself competitively in this space both economically and militarily. And with technological advances in energy, navigation, and communication making AVs more attainable and affordable, the increasingly autonomous future of Army logistics is nearly here.

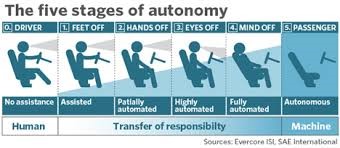

In order to understand what this future might look like, we first need to consider the five stages of vehicle autonomy, which go from Stage 0 (completely human-driven) to Stage 5 (completely machine-controlled). The stages in between are characterized by what the human driver can “take off” while driving. For example, in Stage 1, the driver can go “feet off,” continuing to control steering while acceleration and braking are controlled by the vehicle. In Stage 2, “hands off,” the driver is alert to the driving environment and able to take control if necessary, but all of the vehicle’s motion, and navigation, is controlled by the vehicle. In Stage 3, the driver can go “eyes off,” monitoring the controls inside the vehicle as the vehicle controls the reaction to the outside environment. And in Stage 4, “mind off,” the driver remains in the vehicle to handle any emergencies but is otherwise uninvolved. Finally, in Stage 5, there is no driver at all.

So that’s how autonomous technology works . . . in theory. But despite all the progress being made, there are still significant practical, policy, and economic issues at play. Perhaps the most vexing is simply getting the technology right. For example, despite billions of dollars of investment and significant technological expertise, automotive giant GM still feels that their self-driving cars “aren’t commercially ready.” Other companies are experiencing similar problems; AV software occasionally “sees” things that aren’t there, or worse yet, fails to react properly to things that are there. There is also a level of discomfort with autonomous machines, some of which is due to unfamiliarity with the system, but some of which is attributable to high-profile failures in the industry. Last March, for example, an Uber AV accidentally struck and killed a woman walking her bicycle in Arizona, and the same month an occupant of a Tesla vehicle died when it inexplicably crashed into a highway median in California while the car’s “Autopilot” system was engaged. AVs operating in some locales have even been attacked by local residents. The potential liability adds to the cost of AV development; for example, any self-driving vehicle operating in China must carry at least $5 million in accident insurance. And even with very high levels of insurance coverage, damage awards in these cases could be ruinous for companies developing AV technology.

What further complicates the path to autonomy is the potential human cost: What will happen to taxi and truck drivers, for example, if every vehicle ultimately becomes driverless? Large employers such as Uber or Amazon might benefit since their labor costs would decrease dramatically, but the potential loss of jobs could stir political resistance to commercial AVs, or could lead to efforts to restrict their operations in certain markets, similar to what happened to Uber and Lyft in New York City.

Despite these challenges, getting AVs right would be an unambiguously positive development for the military. Depending on the situation on the ground, AV technology could make convoys significantly safer for humans and easier to coordinate by having just one manned vehicle at the front with autonomous vehicles following behind. This allows humans to make decisions in real time as contingencies arise, but exploits the advantages provided by the Stage 5 (fully autonomous) vehicles following behind, a process known as “expedient leader-follower” (ExLF). This has the potential to save countless lives as fewer people would be at risk of improvised explosive devices and commanders would have to worry only about protecting the lives of the soldiers in the manned vehicle in the front rather than those sitting in each vehicle in the convoy. Once the technology is mastered, integrating ExLF might be as simple as adding drop-in kit, allowing logisticians the flexibility to operate within the full spectrum of AV capabilities.

As with any emerging technology, Army doctrine will need to incorporate the changes that autonomous technology will bring. But while it might take doctrine time to catch up with technology, the military advantages of AV are clear. In addition to the targeting and intelligence capabilities mentioned earlier, AV’s offer the potential to dramatically increase the speed, accuracy, and capacity of logistics delivery, thereby markedly improving the sustainment warfighting function. It could also be very useful in positioning troops and moving them into, or evacuating them from, combat zones. Autonomous vehicles could also serve in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief missions, where they might be used to transport aid workers, to provide supplies to remote locations, and for evacuation.

But perhaps the greatest advantage that autonomous tech can offer is in the area of force protection. Fielding autonomous vehicles significantly reduces the number of soldiers and contract drivers put in harm’s way. In both Afghanistan and Iraq, many lives were lost in attacks on vehicles and through simple accidents; extensive use of AV’s can help mitigate that. This technology will be especially important in future wars, which are most likely to occur in dense urban areas, where the greatest danger might come from something as routine as crossing the street. Protecting logistical capabilities will ensure that more of it is available when it is needed.

Fortunately, the Army has not been standing idle when it comes to AV development. Although testing has thus far been fairly modest, it has been ongoing. The Army is using autonomous vehicles to transport troops back and forth to local medical facilities at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for example, and achieved success in limited convoy testing conducted this past May. But there is still much that remains to be done, especially if the Army continues to partner with, and learn from, the private sector.

The potential is clear: when this technology is mature and fully integrated into the operational force, autonomous ground-based vehicles will be able to move further, faster, with more payload, and into more-dangerous situations in support of Army logistics. Our military needs to work to remain ahead of its competitors in creating, maintaining, and improving this technology. We need to ensure that AV “logistics” catch up with AV “tactics.”

Lt. Col. Charles Faint is a career US Army intelligence officer who served seven tours in Iraq and Afghanistan with the 5th Special Forces Group, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, and the Joint Special Operations Command. He is a Yale University graduate and Temple University DBA candidate, and is currently assigned to the intelligence staff at US Army Pacific. He also owns the popular military-themed blog The Havok Journal.

Uriel Epshtein is the executive director of the Renew Democracy Initiative and the founder of the Peace & Dialogue Leadership Initiative, and has worked in the startup world with companies including Uber and DoorDash, focusing on the strategy and operations of mobility. He is a Yale University graduate.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or any other organization.

Image credit: Staff Sgt. Kenneth Holston, US Air Force