What are the second- and third-order effects of killing Qassem Soleimani? On its face, this is a reasonable question to ask, and one that many people have. Rather than being used in a neutral way, however, asking for precision about consequences is often deployed as a rhetorical device to challenge any action in a way that conflates uncertainty with negative outcomes. However, a decision can simultaneously increase uncertainty and utility. Put another way, it may be correct to choose a beneficial chaos than a harmful order. Mistaking uncertainty for necessarily negative outcomes is bound to lead to poor judgment, in the case of killing Soleimani and beyond.

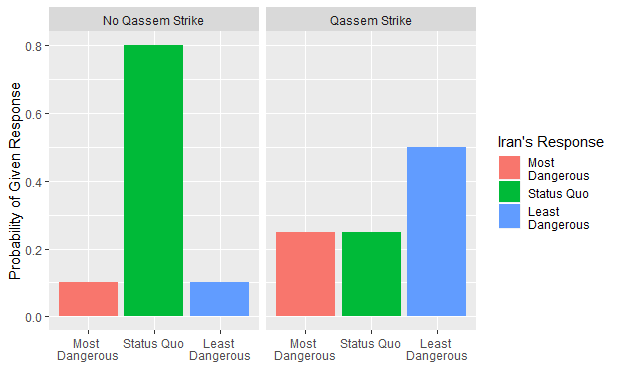

A simple model can be used to depict two distinct scenarios that illustrate how a decision that increases uncertainty (killing Soleimani) can either increase or decrease expected utility. To simplify matters, we group Iran’s choices into three options: the most dangerous (an all-out assault on American interests and allies), the middle (maintenance of the status quo of sniping at American interests), and the least dangerous (reduction of Iranian interference in contested spaces). Each of these options has a “payoff” in utility to American interests and a likelihood that are quantified for this exercise: -1 for the most dangerous, 0 for continuing the status quo, and +1 for the least dangerous. In the first scenario, killing Soleimani increases the likelihood of an American-Iranian war yet also increases America’s expected payoff.

This scenario—with higher variation but a better average outcome—is not far-fetched. The United States has had the opportunity to kill Soleimani before yet has chosen not to. The American strike therefore represents a new American strategy. Iranian strategy has obviously been devised in accordance with the previous American strategy. It might therefore not be suited to this new American strategy. Iranian leaders could view this as the moment to either “fold” or “go all in.” Either way, an Iranian change in strategy is advisable given the new strategic context. If deterrence works the way that the architects of the American strike hope it does, then this change is more likely to be favorable (Iran adopts the least dangerous option) than unfavorable (Iran chooses the most dangerous option), as in the above example.

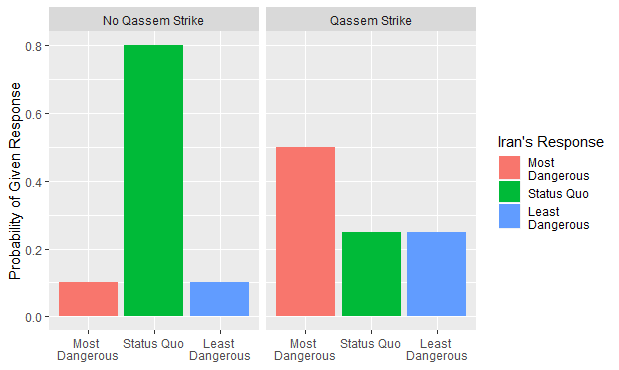

On the other hand, a second scenario shows how killing Soleimani could result in a lower payoff. If killing Soleimani changes Iran’s calculus but makes the regime more likely to seek a war than to back down, then America has lowered its average payoff by killing Soleimani. This alternative is shown below.

The judgement of relative risks relies on assessments of psychology and decision making that are, of course, up for debate. With that in mind, note the shift in this model from “uncertainty” to “risk”: in economics, risk is quantifiable (e.g., the lifetime odds of being hit by a car is one in 4,292) while uncertainty is not (e.g., what will the automotive industry look like in thirty years?). Outside of science fiction, everyone knows that geopolitical events are uncertain and not risky (in the sense that their likelihood is not quantifiable). Yet we’d be paralyzed if we simply threw up our hands and refused to at least try to estimate levels of uncertainty as if it were quantifiable. In many situations, judgment can even be improved by forcing individuals to assign numbers to uncertain events and treat them as risk. It is important to maintain a healthy skepticism about future predictions while refusing to be incapacitated by the complexities of the world.

Military history is full of commanders who embraced uncertainty to defeat their certainty-bound opponents. For an obligatory Clausewitz reference, see this quote from On War: “There are cases in which the greatest daring is the greatest wisdom.” Robert E. Lee danced circles around the hesitant George McClellan, about whom Lincoln famously quipped, “If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time.” In the French campaign of 1940, Erwin Rommel pushed his division so deep into enemy territory that it became known as the “ghost division,” because it couldn’t be located by either his enemies or his own higher command. The Marine Corps’ own Gen. Jim Mattis embraced the callsign “Chaos.” Embracing uncertainty is essential to commanding troops and making decisions.

Returning to the current situation with Iran, the utility of killing an individual responsible for many American deaths needs to be weighed against the likely changes in Iranian behavior. On one hand, Iran experienced mass protests in 2018 and again in December 2019, which indicates that domestic considerations could increase the costs of escalation for the Iranian regime. On the other hand, even though targeting Iranian interests outside of the country itself avoided adding a violation of Iranian sovereign territory to Iran’s grievances after Soleimani’s death, large anti-US demonstrations suggest the strike could strengthen Iranian unity and benefit the regime.

The strike was also clearly made in response to the storming of the US embassy. Iran’s gradually escalating attacks on American interests and partners in past years have taken the form of the “salami-slicing” tactics described by Thomas Schelling in Arms and Influence. In defining this conundrum, Schelling describes his children slowly taking steps out into the ocean while looking back to see when their parents will stop them. By gradually increasing its aggression, Iran has not given the United States a clear point to initiate a punishing attack that would signal its resolve. The escalatory exchange of an Iranian-backed group’s rocket strike in Kirkuk, America’s killing of Iranian proxies, the storming of the American embassy, and finally killing Soleimani has decreased this ambiguity. These escalatory steps by the United States make the continuation of Iran’s previous salami-slicing tactics illogical. Yet uncertainty remains: de-escalation might be economically rational for Iran, but escalation might be the choice for a society steeped in the values of martyrdom.

The task now that the strike was conducted is to take steps that influence the current balance of uncertainty in the favor of American interests. It is important that we further increase the likelihood that Iran will choose de-escalation by giving the regime in Tehran a face-saving opportunity.

Drawing down the number of American troops in Iraq, for example, could offer Iran such an opportunity and increase the likelihood of Iran choosing de-escalation. The United States has delivered a clear message that its strategy has changed and that attacks on its personnel will be met with serious retribution. It will be easier for Iran to choose the least dangerous option if the regime can present it to both domestic audiences and potential foes in the region as a victory. A drawdown is in line with the Trump administration’s stated goals, and the continued presence of US troops in Iraq has done little of late to increase US influence in their government; in fact, it incites many people in the country against us, à la David Kilcullen’s description of the accidental guerrilla.

Regardless of differences of opinion on the ramifications of killing Soleimani, a shared framework is needed for discussion. Uncertainty is not always negative, as historical examples and simple models show. Intelligent risk-taking is a critical element of successful strategy, in dealing with Iran and beyond; whether this strike was “intelligent” or not remains a matter of debate.

Image credit: khamenei.ir (via Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International)