Over the centuries—from Caesar’s pilum at Gaul to Henry V’s longbowmen at Agincourt to the modern-day soldier—commanders have required soldiers’ individual lethality combined with collective proficiency for mission success. This has been true with each change in the character of warfare, even as the nature of war has remained static. The conflicts in Ukraine and Israel highlight the latest evolutionary step in the character of war—the broad integration of unmanned aircraft systems—and make apparent the consequent need for the Army to ensure detection and defeat training proficiency, individually and collectively. But what are the necessary training practices and standards, and how are they communicated across the force? Current practices of stating training conducted without terms of reference are too subjective and lead to misunderstandings and frustration. Something more is badly needed. Senior leaders must develop the necessary training guidance and communicate training proficiency on unmanned aircraft systems and detection and defeat systems, consistent with foundational doctrinal procedures.

Today, most soldiers, regardless of rank, intuitively understand the importance of unmanned aircraft systems and their detection and defeat systems. There are discussions on Capitol Hill about the need for a Drone Corps, and social media videos depicting young Ukrainian soldiers using off-the-shelf drones to defeat multi-million-dollar main battle tanks and the Israel Defense Forces using drone swarms to identify and target militants further highlight the importance. However, there are no clear ways to communicate readiness at echelon. A quick glance at Army Training Requirements and Resources System offers options for functional training on operating small unmanned aircraft systems, for example, and on joint counter small unmanned aircraft system. The functional schooling, combined with prioritized theater efforts in training defensive weapons and systems as well as combat training center and mobilization force generation installation efforts to incorporate individual skills into collective events, are beginning to offer increased readiness. But as a service, senior leaders must consider how readiness is built and communicated in support of Chief of Staff of the Army General Randy George’s four focus areas of warfighting, delivering ready combat formations ,continuous transformation, and strengthening the profession of arms?

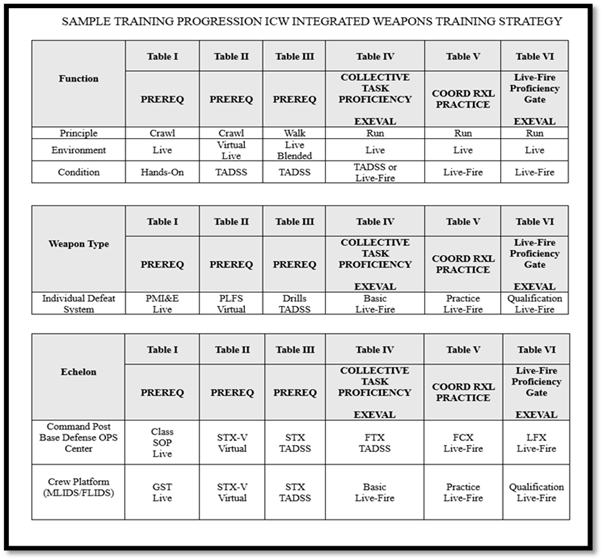

Per Training Circular 3-20.0, Integrated Weapons Training Strategy, “The integrated weapons training strategy is an overarching, integrated, and standardized training strategy for the maneuver commander to train, evaluate and assess their unit’s overall proficiency at home station.” Based on this, three imperatives stand out when it comes to training of unmanned aircraft systems and counter–unmanned aircraft systems. The first is to include react-to-air (both mounted and dismounted) battle drills within warrior tasks and battle drills. The warrior tasks and battle drills are common to all soldiers, regardless of rank or specialty, to best prepare soldiers and increase readiness. Currently, however, react-to-air battle drills and associated tasks are not within the Army Warrior Training Plan to set the conditions for collective training events. As the character of war evolves to more prominently feature drones, changing this is not only reasonable but critical. Second, leaders should follow the individual weapons training strategy in communicating readiness according to defined gates and tables as depicted below. Finally, leaders must find every opportunity to introduce and reinforce organizational lethality into all training events—from training soldiers at the halt in assurance of 360-degree and three-dimensional security to posting an air guard on a vehicular movement to accounting for the changing character of war specific to its organization. In short, the progression from Table I to Table VI should not be in isolation but should complement individual lethality to maneuver formation progression and overall organizational capability.

Consider an infantry battalion that has completed Table I to Table VI for platoon-level proficiency and is ready to begin the company-level situational training exercise in preparation for the combined arms live-fire exercise. Concurrently, the battalion command post / base defense operations center and maneuver formations are task organized with soldiers and leaders trained and certified with individual drone-defeating systems and certified crews on detection and defeat systems. The maneuver formation situational training exercise and combined arms live-fire exercise should include the exercise of command post functions and detection and defeat systems organic to the organization.

A way to set conditions for the standardized training strategy is paramount to the discussion, too. Currently, a modified table of organization and equipment does not account for manning of small units or training operators with systems not organic to the organization and leaders must task organize for the operational environment without losing capability. Continuing the example of the infantry battalion, unit leaders should task organize early within the training cycle or notification of deployment. The first step is to determine business rules for the right talent—the who and why regarding assignment to serve within the unmanned aircraft system detection and defeat formations and the command post / base defense operations center. The second step is to determine what organization the right talent is coming from early and how to maintain an enduring capability for the mission of the organization. For instance, once the right talent is selected, the remaining soldiers and leaders are assigned within rifle squads and platoons. The removal of two riflemen from each nine-soldier squad yields fifty-four soldiers available for new equipment training without undue loss of capability with the shift to seven-soldier squads. The removal of riflemen allows leaders to build a capability and maintain squad and platoon certifications. Upon assignment or change of mission, newly assigned soldiers should be certified as riflemen. Finally, the fifty-four-soldier cohort serves as the baseline capability of unmanned aircraft systems and detection and defeat systems.

Leaders best communicate a soldier’s individual lethality and collective proficiency by placing them in the context of known definitions and terms of reference. For the emerging challenges—and opportunities—associated with unmanned aircraft systems, the warrior tasks and battle drills and integrated weapons training strategy offer an answer. While the example described above does not account for every type of formation, mission, or variable, it does offer a starting point for the critical discussion about how leaders should communicate solutions in unmanned aircraft system training proficiency levels.

Command Sgt. Maj. Vincent Simonetti, a career infantryman, serves as the division command sergeant major of First Army Division West. First Army Division West partners with the Army National Guard and the US Army Reserve to enable leaders and deliver trained and ready units for combatant commands in the mobilization and demobilization of upwards of thirty-five thousand soldiers per year.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt Raquel Birk, US Army