In the American Revolutionary War, British soldiers employed orderly, neat formations that they had perfected in European battlefields, but that were worthless against colonial rebels. More than two centuries later, NATO faces its own version of the redcoats’ problem. Like the British Army two and a half centuries ago, NATO risks irrelevance by training Ukrainians for idealized battles, not their chaotic, drone-heavy, attritional war.

Ukrainian units are not facing conventional battles of the form NATO plans and prepares for. They contend with artillery barrages, drone swarms, chemical munitions dropped from the air, and trench warfare, a sort of cyberpunk warfare resembling parts of both World War I and World War II, mixed heavily with modern technology. While the Ukrainians have adapted to these conditions with creativity, resilience, and speed, Western training programs remain mostly rooted in prewar doctrine, ignoring the radical evolution of battlefield dynamics.

Based on fieldwork in Ukraine and our observations at German bases under the European Union Military Assistance Mission–Ukraine (EUMAM UA) and US-led Joint Military Training Group–Ukraine (JMTG-U) at Grafenwoehr, along with internal documents from the Security Assistance Group–Ukraine (SAG-U), we argue NATO must lose outdated training models, and learn from Ukraine’s frontline innovations to prepare for future wars.

The Battlefield Reality: What Ukrainians Actually Need

Three years of grinding attrition have rewritten the rules of modern combat in Ukraine. According to a SAG-U report, Ukrainian troops endure harsh “zero line” conditions—long foot movements under constant threat from first-person-view drones and precision-guided munitions. Movement itself is a hazard, demanding pattern avoidance, camouflage, and terrain adaptation—skills often absent from Western infantry training. Effective training must prepare Ukrainians to counter drones enabled by fiber-optic cable, build deeper bunkers, and counter tunneling threats. Moreover, Ukrainians tell us they need battlefield medicine adapted for high-casualty environments, where evacuation may take up to a week via a motorbike.

Ukrainian soldiers also operate under relentless surveillance from drones, to include drones dropping chemical munitions. Yet Western training rarely includes battlefield stress inoculation, preparation for maneuvering at night, or how to dismount during a mechanized assault. Valerii Zaluzhnyi, Ukraine’s ambassador to the United Kingdom and former top general, has emphasized decentralization and mental resilience as vital for survival, a cultural shift NATO must study. Still, Ukrainian requests for drone countermeasures and trench fortification training are sidelined in curricula built for conventional or peacekeeping operations, despite their proven effectiveness.

JMTG-U instructors from the Pennsylvania National Guard (2024–2025 rotation) brought experience and passion, but often struggled against institutional limits: outdated software, poor doctrinal translation, limited resources, and unrealistic rehearsal timelines. As their commander noted to us, planning cycles were difficult to schedule because they were dependent on borrowing equipment from other US units to improve training quality for the Ukrainians.

In interviews, Ukrainian soldiers voiced frustration that NATO instructors often push textbook solutions, like deliberate planning cycles, to nontextbook problems such as surviving drone swarms and coordinating maneuvers in an environment characterized by a highly contested electromagnetic spectrum. Russian and Ukrainian soldiers adapt new tactics on the front line faster than NATO can update its courses, a challenge compounded by restrictive safety regulations on Western training grounds. Unfortunately, Ukrainian training derived from NATO doctrine does not fully prepare them for battlefield changes and adaptations, which occurs every two to six weeks.

The urgent priority is to reverse the flow of lessons—taking the field experience of Ukrainian units and using them to transform how NATO trains its own forces for the wars of tomorrow. To continue training Ukrainians as if they will fight NATO’s next conventional war rather than their current existential one risks more than irrelevance—it risks building paper battalions while Ukraine bleeds, and it threatens NATO’s credibility.

Training Gaps and Cultural Mismatches

Western training programs, while professional, falter on cultural and doctrinal mismatches. Language barriers persist: JMTG-U uses Ukrainian interpreters to build trust, but EUMAM UA sites rely on Russian-speaking interpreters, risking friction given Ukraine’s desire to promote the Ukrainian language and encourage English proficiency in its security forces. Cultural disconnects also erode cohesion. For example, Ukrainian soldiers refused to use a command post known as Building 200 due to Ukrainian forces’ use of the number 200 to indicate a fatality (300 is also a loaded term because it’s used to refer to wounded personnel). German instructors dismissed their concerns, ignoring this symbolism, which would be much like overlooking an American aversion to a thirteenth floor. Cultural respect isn’t a nicety—it’s a requirement for effective training and cohesion.

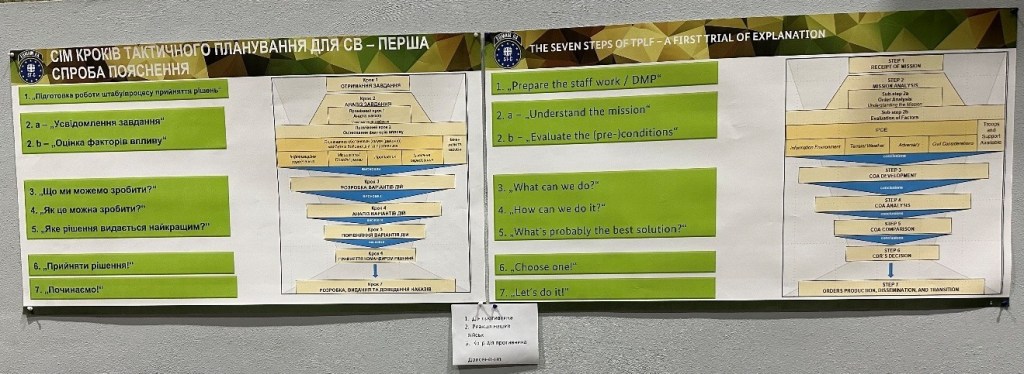

Doctrinally, NATO’s rigid planning models assume resources and time Ukrainian units lack. As Zaluzhnyi noted, success demands rapid adaptation, not bureaucratic templates. These gaps hinder not just training but NATO’s ability to learn from Ukraine’s front lines. Unfortunately, many trainers from NATO countries insist on rigid adherence to doctrinal templates, even when they do not align with battlefield realities. The German-led brigade staff training standard operating procedure developed under EUMAM UA draws from NATO APP-28 and emphasizes formal planning steps such as mission analysis, course-of-action development, and decision-making, along with supporting activities like wargaming and synchronization. While sound in theory, this approach often struggles under wartime constraints where Ukrainian have minimal time with degraded communications and incomplete staff structures. A senior German colonel we interviewed, who helped design this standard operating procedure, explained that although it incorporates battle rhythm discipline and standardized staff roles, it assumes organizational capacity that Ukrainian brigades often lack.

By contrast, the US Army’s MDMP, outlined in ATP 5-0.2, emphasizes iterative commander-driven planning, tailored for formations with extensive intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and support infrastructure. The German-Ukrainian standard operating procedure, while more NATO-aligned, attempts to account for partner nation constraints—adding emphasis on electronic warfare, resilience training, and rapid course-of-action formulation. Yet even with these adaptations, it remains too rigid for the tempo and improvisation demanded on the Ukrainian front lines. This reflects a deeper issue: training focused more on making Ukrainians look like NATO units than on equipping them to win their current war. In fact, the German colonel running the staff training program for Ukrainian staff officers used a wargame scenario straight out of the Cold War, refusing to add drones and other modern weaponry.

Ukrainian commanders face a dilemma: aspire to NATO’s professional, interoperable standards or embrace the improvisation needed to survive. Western trainers, particularly under EUMAM UA, push structured planning doctrines ill-suited for Ukraine’s chaotic battlefield, where plans must be formed rapidly. NATO’s templates, requiring extensive documentation and rehearsals, create bureaucratic fatigue for units of mobilized citizens with limited training time. As Zaluzhnyi emphasized, Ukraine is forging its own way, blending professionalism with adaptability. Without a feedback loop to capture these realities, NATO risks training a Ukrainian Army in its own image, not the military Ukraine needs.

Until training missions internalize the reality of Ukrainian battlefield conditions, they will keep training for theoretical wars. Without cultural attunement and doctrinal humility, even the best-intentioned Western assistance generates friction, misunderstanding, and missed opportunities.

The Army NATO is Creating or the Army Ukraine Needs?

Ukrainian commanders today straddle a complex divide. On one side is the aspiration to become a NATO-style military: professional, hierarchical, and interoperable. On the other is the urgent need to wage a brutal, cyberpunk war of survival. Western advisors often focus on building the former, but battlefield necessity demands the latter. This disconnect is especially clear in brigade and battalion staff training.

Under EUMAM UA, Western trainers introduce Ukrainian officers to advanced planning doctrines focused on synchronization and full-spectrum staff processes. But Ukraine’s battlefield reality rewards improvisation, rapid decisions, and decentralized execution. As one brigade commander noted about his unit receiving staff training in a SAG-U report: “We appreciate the instruction, but we plan our fights in three hours, not three days.” This has been a primary point of contention over the last three years, where the Ukrainians are caught between surviving in the moment and building a resilient and coherent force for the long-term.

At JMTG-U, the commanding officer cited delays driven by incompatible software, incomplete annex templates, and unrealistic rehearsal requirements. Staff were buried in documentation—producing operations order annexes and matrices often irrelevant once the battle began. The result: bureaucratic fatigue and rote planning that failed to shape actual operations.

European instructors often emphasize deliberate battalion-level planning and combined arms integration. Yet most Ukrainian units are composed of mobilized civilians with little time to train. Officers rise through battlefield merit, not staff college credentials. Doctrine must be translated—not just linguistically, but operationally—to reflect the force Ukraine has. As Zaluzhnyi himself emphasized, “Changes will be required in the doctrine that promotes and facilitates the adaptability of the armed forces.”

This is the golden middle dilemma, between professionalization and improvisation. As Zaluzhnyi recently stressed, “We are no longer copying others—we are learning to fight in our own way.” NATO must train for that future, not its own past.

NATO’s training lacks a critical component: a feedback loop linking battlefield outcomes to classroom instruction. Trainers assess success through classroom performance, not combat effectiveness, leaving them blind to whether skills translate. A Ukrainian officer noted that some NATO tactics were impractical due to terrain or equipment shortages. Structural barriers—outdated simulations, mistranslated doctrines, and limited polling tools—compound the issue. Senior US officials, per a SAG-U report, worry that reduced Ukrainian feedback undermines assistance efforts. When JMTG-U’s drone course was redesigned after Ukrainian critiques, it proved the value of frontline insights. NATO needs a battlefield-to-classroom pipeline to capture these lessons, setting the stage for reverse advising.

The Problem of Training Feedback Loops

Despite years of instruction and assessment, trainers often lack visibility into whether their lessons are used—or useful—on the battlefield due to a lack of feedback loops. This creates a blind spot where validation is anecdotal, delayed, or entirely absent. Or in many cases, improving the quality of training is dependent on a proactive instructor staying in touch with Ukrainians they’ve trained, usually via a Signal chat room.

A SAG-U report described this disconnect as “training in a vacuum,” where trainers assess success based on classroom performance and doctrinal adherence, but rarely see how those skills perform under fire. One Ukrainian officer noted that some NATO tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) were theoretically sound, but unusable due to terrain, tempo, or equipment constraints.

The lack of battlefield feedback has strategic consequences. According to a SAG-U officer, some Washington policymakers have lamented how Ukrainian officials were sharing less feedback on battlefield development, prompting them to question whether security assistance was worth it if the Ukrainians weren’t sharing tactics and lessons. Without clear messages reaching the Pentagon, it becomes harder to advocate for needed support and to adapt programs to the evolving fight.

The commanding officer at JMTG-U also identified multiple structural obstacles: insufficient data collection infrastructure, broken simulation platforms, lack of resources, and missing or mistranslated doctrinal documents. Even basic tools like wargaming support and course-of-action comparison tables were sometimes incomplete or delivered too late to matter. In his final evaluation, the JMTG-U commander recommended integrating Ukrainian officers into the curriculum development process to improve realism and close the loop between instruction and implementation. In one case, when JMTG-U instructors developed a drone course, Ukrainian trainees “ripped up” most of the training program because it did not match their battlefield experience, a common complaint of many Ukrainians we interview. Ukrainian inputs led to a complete redesign—producing a far more realistic training module based on frontline drone TTPs, which was finally demonstrated in June 2025 by the new Tennessee National Guard rotation at JMTG-U.

Finally, some digital polling tools for improving tracking are being beta tested, which is a step in the right direction. Such platforms allow Ukrainian soldiers to rate training modules and provide post-training feedback. However, they remain limited in scale and primarily measure satisfaction rather than tactical efficacy. To go further, NATO needs a battlefield-to-classroom pipeline—a formal structure for gathering after-action reviews, combat observations, and tactical innovations from Ukrainian units and pushing them into training course development. Scholarship has described the US military’s historical reluctance to absorb operational lessons in real time. NATO now has a chance to prove it can evolve faster, not just smarter. We can no longer risk allowing after-action reports of Ukrainian training to be uploaded into a blackhole SharePoint website, never to be read again.

Reverse Advising as the Strategic Imperative

Security force assistance has traditionally been a one-way street: Western advisors arrive, impart doctrine and TTPs, and leave. Ukraine challenges this model: Ukrainian troops create new drone tactics, develop underground command bunkers, and decentralize reconnaissance-fire networks that are survivable in a sensor-rich and electronic warfare–intensive battlespace. Such battlefield adaptations are not just wartime improvisations—they are sources of institutional knowledge.

This is why NATO must embrace reverse advising—not as a rhetorical flourish, but as a structural transformation. Ukraine is a laboratory for modern warfare; adaptation, as much as technological supremacy, defines the current fight. Zaluzhnyi has noted that Ukraine’s early battlefield experiences with AI-enabled systems represent “a profound and relevant change in the characteristics of warfare.” War-winning capability lies not just in hardware, but in the agility to employ it creatively under pressure. For instance, the French Army appears the most poised to learn and innovate from the Ukrainians. Interviews with French trainers indicated that they were developing a new infantry-drone manual based on feedback from Ukrainians they had trained. This development suggests why the French recently designed and developed 3D printing labs, which are highly mobile and allow their soldiers to produce ten drones every three hours.

To systematize reverse advising, institutions such as NATO’s Allied Command Transformation and the new NATO-Ukraine Joint Analysis, Training And Education Centre must be empowered to capture frontline innovations and rapidly integrate them into allied doctrine and training. Battlefield TTPs from Bakhmut and Robotyne should be analyzed and integrated within weeks—not studied abstractly years later. NATO should adopt mechanisms used by the Ukrainians themselves: crowdsourced battlefield intelligence, iterative TTP updates, rapid-turnover rehearsal drills, and integration of open-source intelligence like Telegram posts and chats.

As the JMTG-U commander recommended, future training cycles must be codesigned with “Ukrainian veterans and leverage Ukrainian planning software like Kropyva and Delta as standard instructional tools.” This level of interoperability is not a luxury, as it’s the only way to ensure Western support actually enhances battlefield survivability.

The Russo-Ukrainian War has revealed an uncomfortable truth: Ukraine may be advising NATO more than the reverse. Recognizing this—and institutionalizing the flow of frontline lessons—will determine whether NATO remains doctrinally relevant. Achieving this shift also depends on building strong advisor relationships with Ukrainian units. By institutionalizing reverse advising, NATO can evolve from advisor to student, ensuring its relevance in future conflicts.

Ukraine’s war exposes NATO’s challenge, an echo of the problem that plagued the redcoats during the Revolutionary War: a reliance on outdated doctrine ill-suited for modern, drone-saturated warfare. From Bakhmut’s chaos to Robotyne’s trenches, Ukraine proves that tactical agility—not just technology—defines victory. As Zaluzhnyi warned, rigid command models falter in today’s fights. NATO must transform advising into a two-way street. Reverse advising must be codified to capture frontline lessons, ensuring that NATO doctrine and TTPs remain relevant and flexible.

The next war—whether in the Baltics, Black Sea, or the Indo-Pacific—will likely resemble Ukraine’s current fight more than NATO’s past ones. As Zaluzhnyi argued, “Political leadership in the conducting of war is the most critical factor . . . defining the objectives of the war, providing the material conditions for defense, and strengthening cohesion.”

If NATO continues to export Cold War–style training, it risks irrelevance. NATO can no longer treat advising as a static export function. It must become a feedback loop—driven by humility and urgency—that captures frontline innovation and institutionalizes it across the alliance. Reverse advising is a strategic necessity, and NATO must not rely on what it teaches, but on what it learns. Otherwise, the United States and its allies will train for the last war and march confidently (and blindly) into the next: disciplined, doctrinal, and defeated.

Major Joshua Hood is a PhD student at Northwestern University and is an intelligence officer in the US Air Force.

Lieutenant Colonel Jahara “Franky” Matisek, PhD, (@JaharaMatisek) is a senior pilot and nonresident research fellow at the US Naval War College, Resilience Initiative Center, Payne Institute for Public Policy, and Defense Analyses and Research Corporation. He has published two books and over one hundred articles on strategy, warfare, and security assistance.

Dr. Anthony Tingle is an independent researcher and author who has been studying and writing on Ukraine since the beginning of the war. He has been to Ukraine multiple times, including in May 2023 in the Donbas near Bakhmut the weekend the Russians officially took the city, and in October 2023 near a town called Robotyne, where he accompanied a Ukrainian special forces unit into combat. Most recently in 2024, he was in the Kursk Oblast with Ukrainian forces. He is a West Point graduate and retired Army officer with a PhD from George Mason University. He can be followed at www.WarVector.com and on his Flash Traffic Podcast.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or those of any organization the authors are affiliated with, including the US Air Force and US Naval War College. This fieldwork was sponsored by a DOD Minerva project to improve U.S. foreign military training (Air Force Office of Scientific Research: FA9550-20-1-0277) until it was DOGE’d in March 2025.

Image credit: Capt. Leanne Demboski, US Army National Guard