Military leaders and analysts consistently highlight the importance of predicting what the future formation should look like to win the next war. Current conflict areas and the rise of drones highlight the need for professional militaries to adapt to remain relevant against evolving threats. The Army Transformation Initiative and its transformation in contact efforts continue to expedite changes in organization and equipping. However, key to the US Army maintaining relevancy is how it adapts the division, as the unit of action, along with its subordinate brigades. Although the division formation has seen some recent organizational changes with artillery, engineers, and sustainment, key and most critical is the lethality of the division headquarters and assigned combat brigades. The speed of drone evolution, supported by AI, is uncomfortable for professional armies. This discomfort is exacerbated when considering procurement times and reliance on traditional combat-tested formations or tactics. This fear is reinforced by the idea that professional Western armies, like that of the United States, will successfully execute maneuver warfare in the new drone-infested operating environment. The sheer size and mass of US Army divisions and brigades is considerable, making them inviting targets for an enemy commander’s kill web. One combat principle remains true: Making contact with the smallest element possible limits vulnerability, and this applies from the squad to the division level. Today, a corollary to that imperative has emerged: That smallest element must be a drone-enhanced unit.

Assuming divisions will be able to rapidly transition from movement to maneuver under contact for the first time in decades without significant friction and casualties is unrealistic. Division-level maneuver is never rehearsed outside of a combined arms rehearsal or digital warfighter exercise. Current exercise design and training environments do not adequately recreate the enemy kill web possible on the modern battlefield. Attempts at innovation at the division level are capability focused, without deep thought on the organizational structures that most effectively employ new capabilities. Despite these shortcomings, there is an opportunity to experiment and learn across formations now.

Getting the next formation right for the future battle requires leaders to be comfortable with the uncomfortable. Understanding what is prioritized for adaptation and what must be kept to execute successful maneuver warfare is critical. The challenge is to develop a framework to find this balance of proven concepts and the uncomfortable but necessary changes the US Army must undertake. The framework should be used to inform the design and task organization for the US Army division. Getting the design and doctrinal template of a US Army division right is critical for winning the next war.

Robotic Transition Period Warfare

First, it is important to recognize that we are in a transitional period of warfare and continuous adaptation is required. Warfare is quickly moving past the era of traditional maneuver, which defined the character of warfare from World War II until the invasions of the post-9/11 wars. This period of warfare will never return. Although robotics in combat are not new, the US military’s counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations of the early twenty-first century expedited the development of drone warfare, and subsequent conflicts, from the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine have dramatically increased the pace of this development. Change will continue to be driven at a rapid pace as belligerents iterate new drone and missile developments and efforts to counter them, presenting a constantly shifting and credible threat to traditional formations, platforms, and tactics. What are some defining characteristics of this transition period warfare?

- Robotic Rise: The number of robots and low-cost missiles fed by increased situational awareness will only continue to increase. This concentration of precise and fast weapons will create periods of extreme, high-intensity combat for manned forces on the battlefield. Additionally, drones will be used outside of targeting and strike operations in all aspects of battlefield tasks.

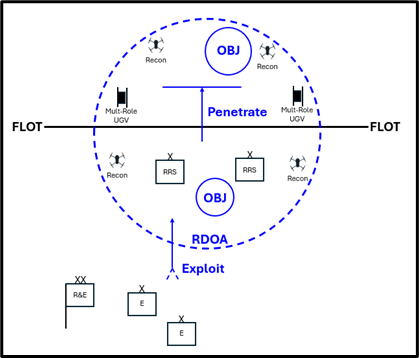

- No Man’s Land: The proliferation of robots and increasing ease of use—and consequent development of their accompanying kill webs—will translate into fewer soldiers required along the contact line. Maneuver is only possible and survivability is only maximized once friendly robots and disaggregated forces have set conditions for follow-on operations. A key task for first-contact units will be the establishment of areas of opportunity where enemy drone activity is suppressed. These areas—call them RDOAs (Reduced enemy Drone activity / Opportunity Area—will allow larger, traditional, and manned formations to operate, exploit, and survive within. Comparable to actions after an airfield seizure, the RDOA allows for forces to go on the offensive from a position of relative advantage. Survivability and infiltration tasks will remain a focus of US Army training, but training cannot model the current Russian way of unsupported infantry probing in areas with high concentrations of sensors and robots.

- Priority Target: Electronic warfare systems and other counterdrone systems will be at the top of a belligerent’s high-payoff target lists. Commanders will know they must keep their drones in the fight and degrade where possible the enemy commander’s capability. There is no doubt that the next counter is antiradiation missiles at the tactical-unit level focused on high energy microwave, laser, and electronic warfare systems.

- Required Adaptation: Units with traditional task organization and mass will not survive using current tactics, doctrinal templates, and manning. Tactics and formations will require continuous adjustment to counter threats and remain relevant.

A Change to Warfighting Function

The fourth characteristic is critical because it requires leaders to change—and to question traditional, and even recent, drone-related success. The robotic transition period of warfare will change certain functions and traditional roles. First, in mission command, junior leaders will see an increase in cognitive load as they confront an enhanced threat and seek to maintain situational awareness. The constant drone threat will require US Army forces to operate and fight in small, decentralized teams until conditions are set for a convergence of forces on an objective. Leaders from the squad to the battalion level will have to be comfortable with fighting in isolated units with minimal communications. This requires leaders at the lowest levels—teams and squads—to have both the confidence and the knowledge to operate accordingly.

In addition, considering maneuver forces, unless RDOAs are established, Army rotatory-wing aviation will be forced to remain tens of kilometers behind the forward line of own troops (FLOT). Air assault and out-of-contact attacks will not be feasible. Sustainment forces must operate in small teams of consolidated categories of supply to survive and simultaneously meet requirements. Their ability to rapidly respond to and support resupply will be critical in exploiting opportunities in RDOAs.

Finally, maneuver forces must lead with robots and focus first on defeating the enemy’s robotics network and supported kill web. Robots cannot be treated as an enabler, but must be considered a part of maneuver forces that could be the main effort until conditions are set for fully manned warfare or larger formations. Although the ground domain is cluttered, it can be assumed that the next conflict will be in and around dense urban areas. This terrain both facilitates and requires leading with robots. As drones move into an increasingly important role the US Army will need to designate specific tasks that these platforms will execute.

In the air domain, primary tasks will be reconnaissance, first-person-view attack roles, resupply, casualty evacuations, and loitering munitions. Weather, threats, and weight restrictions will limit some air operations, and the Army will need to field a ground drone capability to ensure layered and continuous effects. US Army ground drones, ideally built on a universal platform, will lead operations and will execute the following tasks: direct and indirect fire attack, resupply, mobility and countermobility, breaching, reconnaissance, air defense, and electronic warfare. The Ukrainian Army has already demonstrated some of these tasks with ground robots. Most recently a ground robot conducted a casualty evacuation behind enemy lines, successfully recovering the wounded service member while not risking others in the process. These tasks are complex operations even with AI augmentation and will require human direction and discernment. When considering protection and security tasks, ground drones will be critical in establishing and maintaining situational awareness and the perimeter of an RDOA. Their endurance and fixed attention support economy of force and warfighter management.

Given drones’ potential and the characteristics of this warfare transition period, the Army should consider experimenting with the task organization of the division unit. This experiment would be comparable to the 1st Cavalry Division’s testing helicopter employment prior to deploying to Vietnam. Instead of helicopters, the future division would reorganize into robotics and exploitation (R&E)–focused units. As the Army Transformation Initiative continues, the lessons learned from this experiment would inform the whole of the Army. The designated division and the experiment would lead the Army’s efforts to determine the right mix of soldiers and robots. One major benefit of drones is the economy of force they bring in a much smaller package. This translates into a lethal, yet more deployable package that requires less sustainment. In an Indo-Pacific scenario—like Chinese aggression against Taiwan—this unit would facilitate rapid force projection and be critical in deterrence and opening engagements.

The two centerpieces of the R&E division are the robotics, reconnaissance, and strike (RRS) brigade and the exploitation brigade. The RRS brigade would have three primary mission sets that are tailored for the evolving battlefield. First, the R&E would conduct counterreconnaissance along the FLOT and contact area. This would facilitate the second mission, conducting reconnaissance and strike attacks to degrade enemy drone operations and the enemy kill web. This builds toward the third mission, creating local drone superiority and establishing an RDOA. Tied into division and corps enablers and the joint force, the RRS brigades set conditions for the R&E division in the deep and close fights. The size and duration of the RDOA would depend on the terrain, enemy threat, available drone inventory, and friendly mission requirements. This also translates into multiple brigade headquarters managing the reconnaissance and security fight, supporting burden sharing.

The drone-to-soldier ratio for the RRS is around 7:3. Risk created by electronic warfare pockets or weather to the RRS is mitigated by fiber-optic-enabled drones, its smaller footprint, and support by other division enablers. Drones are cared for and operated by soldiers conducting operations from the division’s organic vehicle platforms (Bradleys, infantry squad vehicles, and Strykers). The mix would be approximately three battalions of multifunctional reconnaissance units and one drone-enhanced maneuver battalion (infantry or armor). This reduced package allows the brigade to have a small signature on and behind the FLOT and serve as an early entry force for the R&E division. AI would be leveraged to facilitate drone employment by operators outnumbered by drones. The brigade combat team type does not matter for this experiment, as the RRS and exploitation brigades would be mutually supporting. Utilizing system-of-record platforms is cost-effective and allows more time for experimentation than waiting for the approval and production of vehicles that don’t currently exist. This type of experiment and design is feasible since it is loosely modeled on the existing combat brigade structure. There would be no change to the R&E division’s fires and sustainment brigades until lessons learned dictate another adaptation.

Once the RRS brigades establish the RDOA, the exploitation brigades would execute traditional offensive and defensive tasks and exploit opportunities and conditions set by the RRS brigades. The drone-to-soldier mix in the exploitation brigade would be inverse, 3:7. Since these are like formations the division commander can allocate resources and task organize across the brigades to meet mission requirements. Based on conditions, the more traditional organized divisions (drone-enhanced) will flow through the RDOA behind the R&E division.

As technology continues to advance, the US Army must balance proven formations with evolving tactics and capabilities. Drones’ capabilities—and consequently, the drone threat—will only continue to evolve, and their overall simplicity and relative low cost will ensure everyone from nonstate actors to belligerent states will utilize them to compete with and fight against the United States. Manned formations will be required to hold key terrain at least for the foreseeable future—but formations composed of soldiers alone are increasingly a relic of a past era. The most effective units on tomorrow’s battlefield will be characterized by optimized mixes of soldiers and robotic platforms. The time gap between now and the next evolutionary leap in warfare is unknown, but the US Army must be ready to fight and win in this gap. That means rethinking our formations now.

Lieutenant Colonel Josh Suthoff recently served as the commander of 3-4 Cavalry. He currently serves in Colorado where he lives with his wife and five children.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Austin Thomas, US Army