In June 2023, days into a major counteroffensive in the Russo-Ukrainian War, Ukrainian forces attacking along a supporting axis faced the task of seizing the village of Novodarivka from Russian occupying forces. Although it was an otherwise unremarkable village, the way in which Ukraine succeeded in the battle is anything but. Ukrainian forces’ decision to discard the initial high-tempo, armor-centric concept of operations they brought to Novodarivka in favor of a slow and methodical dismounted infantry–centric approach reveals much about armor’s limitations on the modern battlefield. Yet it also yields clues about how to overcome those limitations, recapturing the advantages of combined arms teams facing prepared defenses.

The Challenge for Armor: US Army Experimentation

At the same time as the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ transition to an infantry-centric concept of operations was causing controversy among Ukraine’s international partners, some one thousand miles to the north, a similar transition was quietly occurring. A US Army battalion task force, TF Mustang—1-8th Cavalry, 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division—in Finland for a series of multinational exercises, quickly realized that attempting to dislodge a defending Finnish mechanized battlegroup tied into Finland’s natural canalizing forests and swamps through mounted maneuver was a losing proposition. Instead, the task force switched to a tactical paradigm of dismounted infantry, scouts, and engineers pulling their accompanying armored formations forward whenever encountering natural or man-made restricted terrain. It was, in effect, a rediscovery of the forgotten defile drill. As two of TF Mustang’s armor officers would note on their experience “Armor [may be] the combat arm of decision, but it still needs the infantry to set conditions and lead the way!”

But while both TF Mustang during exercises in Finland and Ukrainian forces at Novodarivka adopted to lead with infantry, it is not the only proposed solution to overcome tanks’ inherent limitations on the battlefield. Earlier this year, Colonel Bryan Bonnema and Lieutenant Colonel Moises Jimenez undertook a broad observation of changing battlefield conditions in Ukraine and reached a very different conclusion, which they presented in the pages of the Modern War Institute. They proposed that armored brigade combat teams (ABCTs) shift from confronting a prepared defense through an approach based on suppressing, breaching, and seizing to one of isolating, suppressing, and destroying.

As a troop commander with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, I have seen the highlights and corresponding benefits of both approaches. At the National Training Center where the unit serves as the opposing force for rotational units, seizure of certain pieces of key terrain like the Snow Cone hill complex, Racetrack, and Crash Hill are routinely achieved only through the firepower of massed armor. ABCTs, however, frequently lose much of that armored combat power in fights not suitable for armored formations. As an example, while Snow Cone may require multiple tank companies to seize, such elements must maneuver up and over the Siberian Ridge or through Red Lake Pass. The latter of these requires an extremely complex combined arms breach by one of the ABCT’s three combined arms battalions. Upon observing or templating Blackhorse mechanized elements from the opposing force in the pass’s vicinity, a combined arms battalion is often quick to execute a doctrinally correct, but nonetheless costly, mechanized combined arms breach.

In contrast, rare is the ABCT that recognizes that the restricted terrain of the pass offers an opportunity. For while the combined arms battalion’s dismounts will have limited use in the seizure of Snow Cone, at Red Lake Pass their ability to maneuver through restricted terrain would serve them and their battalion well in climbing the pass’s steep walls to conduct antiarmor ambushes on defending Blackhorse mechanized elements. These elements, who mimic pacing threat mechanized formations, are equally if not more infantry-poor than an American ABCT. By employing dismounted infantry, the ABCT forces the defending force to debate staying in position to defend the pass’s complex obstacle belt while under heavy direct and indirect fire or cede the key terrain by retrograding to subsequent battle positions of out of Javelin missile range. Either Blackhorse course of action limits the amount of destruction visited on the combined arms battalion’s mounted formations prior to their moment of actual greatest use, the seizure of Snow Cone.

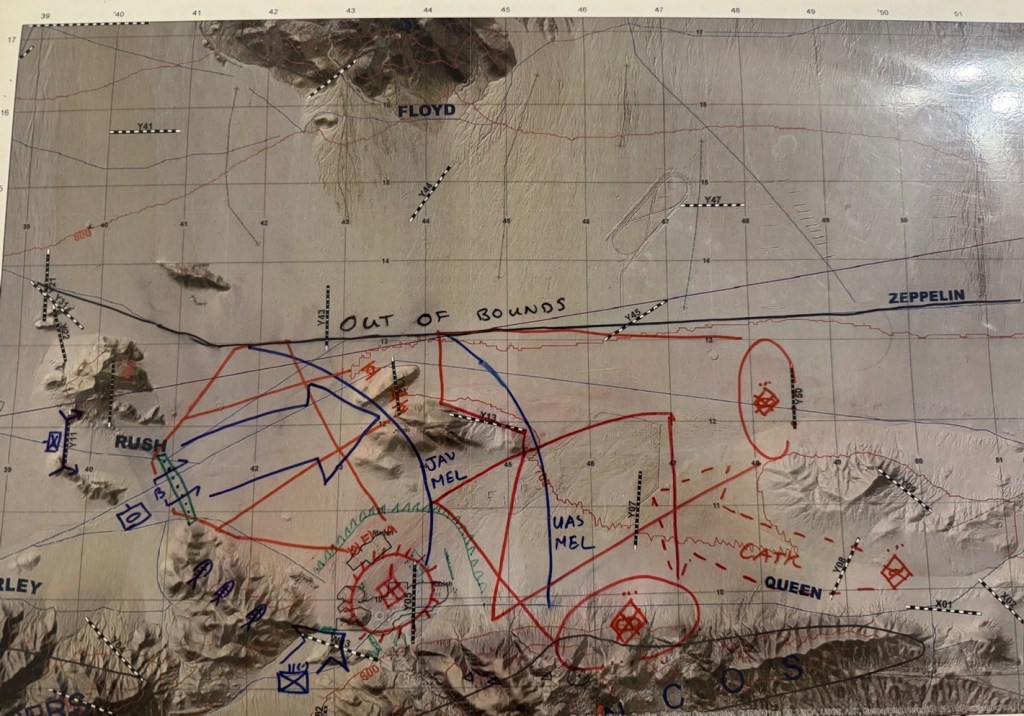

In the case of Colonel Bonnema and Lieutenant Colonel Jiminez’s proposed approach—isolate, mutually suppress, and selectively destroy—while no US Army ABCT currently possesses the array of capabilities required to execute it, an experiment within Project Convergence Capstone 5 conducted at the National Training Center in March 2025 inadvertently trialed the concept in miniature. Two American battalion task forces, one armored and one light infantry, augmented with a suite of autonomous breaching capabilities and various strike and reconnaissance unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), attempted to seize the city of Razish from a Donovian mechanized infantry battalion. For the opposing force commanders, their mission of defending a minefield placed between Moose Gardens and Chod Hill demanded the deployment of a mechanized infantry company along the western side of Razish, a mechanized infantry platoon on Hill 780, and a second mechanized infantry platoon as a counterattack force staged just north of Hill 760 (see map below). Unexpectedly, among the two battalion task forces, the light infantry moved first, air assaulting into Hidden Valley and climbing up the south flank of Chod Hill, from which concentrated Javelin fire would all but eliminate the defending mechanized infantry company and enable the attacking armor battalion to easily breach the obstacle belt and establish an outer cordon of the city.

Stung by this result, the defending mechanized infantry battalion reduced the Razish mounted element to just a single platoon tucked into positions blocked from Chod Hill Javelins by the city’s existing urban architecture, while placing a full company on Hill 780, a defensible terrain feature assessed to be mostly out of Javelin range. However, while this would cause the loss of only a single vehicle to antitank fires, it exposed the Hill 780 element to a continuous stream of reconnaissance and strike UAS, grounded the previous day to inclement weather conditions. In combination with highly lethal artillery fires, these effects would again all but eliminate the defending company and enable a fairly uncontested breach by the attacking armor battalion.

At this point, smarting from two fresh defeats, a startling conclusion became apparent to the mechanized infantry battalion’s leadership. While each individual UAS had its own important strengths and weaknesses, in aggregate they had fundamentally disrupted Blackhorse’s scheme of maneuver. Their reconnaissance and strike capabilities, when combined with supporting fires and antitank missiles, created such a lethal environment that the defending mechanized infantry battalion was forced to transition to a defense in depth. This left only two platoons forward to provide the scenario’s requested contested breach, while positioning the rest of the battalion east of Hill 780 and out of assessed Javelin and UAS range. Project Convergence Capstone 5’s testing scenario inadvertently gave the attacking force enough organic capability to operationalize Colonel Bonnema and Lieutenant Colonel Jiminez’s instruction to deliberately isolate battalion objectives and suppress their defenders prior to the commitment of the main body.

While both the defile drill employed by TF Mustang in Finland and the tactical paradigm of isolate, suppress, and destroy effectively used by the two battalion task forces during the Project Convergence Capstone 5 offer ways in which ABCTs can better posture themselves to fight through man-made and natural restricted terrain, both approaches come at a cost. They trade the ABCT’s concentration of mass for dispersion while downshifting its perceived rapid pace of operations and relying on limited numbers of dismounted elements to pull forward their awaiting mounted counterparts. So are there alternative tactical and operational approaches that overcome armor’s vulnerability while preserving an ABCT’s mass and power for follow-on missions?

Applying History to Armor’s Modern Challenge

Again, history offers instruction. While many have compared the Ukrainian counteroffensive in the summer of 2023 to the Allied invasion of Normandy, few have made the better comparison to the US Army’s breakout from the beachhead some six grinding weeks of attrition later: Operation Cobra. Yet, unlike the British breakout attempt, Operation Goodwood, during Cobra the Americans led with infantry. The 1st, 4th, 9th, and 30th Infantry Divisions, each supported by an attached independent tank battalion, broke into the German positions before conducting a forward passage of lines with trailing armored divisions that would conduct the operation’s critical breakout. Largely dismounted infantry formations advanced through restricted terrain supported by limited quantities of armor to destroy entrenched formations, before unleashing mechanized formations for the operation’s breakout phase. This was the exact concept of operations trialed in the later stages of the Battle of Novodarivka and attempted, albeit unsuccessfully, in the larger context of the summer 2023 counteroffensive.

To be clear, this does not mean others, including the authors referenced earlier in this article, are incorrect to suggest that the ABCT is capable of fighting through restricted terrain with modified tactical concepts. Yet, while ample video exists of Ukrainian Abrams and Bradleys occupying attack-by-fire and support-by-fire positions to devastate Russian trenches in support of dismounted infantry elements, the question remains whether such vehicles and such armor-heavy organizations are always the best tool for the job—especially considering ABCTs comprise just fourteen of the Army’s fifty-eight total brigade combat teams. Instead, could such mobile protected firepower also be provided by a light tank or assault gun attached as a divisional asset to an infantry brigade combat team, either mobile or Stryker, operating ahead of its armored brigade counterparts?

Admittedly, this is a controversial proposal. As the cancellation of the M10 Booker shows, the concept of sending Americans into harm’s way in vehicles possessing anything less than the finest amount of protection is nearly sacrilegious, as is leading with more vulnerable, casualty-prone dismounted forces when a multitude of armored vehicles could similarly accomplish the mission. However, in penetrating a prepared defense, particularly considering the modern extension of the battlefield and pervasive adversary sensor-shooter networks, an armored formation may reduce immediate risk to force but may counterintuitively increase the risk to force over a sustained breakthrough attempt, while universally increasing the risk to mission accomplishment.

In a breakthrough attempt, it is highly likely that armored forces take high losses to a prepared adversarial defense. Yet, as demonstrated throughout twentieth-century military history, the benefit of armor is that those losses are greater in terms of equipment and less in terms of casualties. And equipment can, following successful breakthroughs, be easily recovered and repaired with a sufficiently well-equipped sustainment apparatus. However, in a failed penetration, or one that gains limited ground, such rapid repair and regeneration is not only extremely difficult but under increasing challenge by tactical reconnaissance-strike regimes that have caused increased tank casualties at beyond-line-of-sight distances and consistently targeted less protected sustainment networks.

As the Ukrainians at Novodarivka, TF Mustang in Finland, and others throughout history have consistently demonstrated, when faced with heavy armor losses, commanders will call for the infantry. However, just as then Colonel Huba Wass de Czege described in a 1985 examination of modern infantry formations, within armor-heavy units infantry is primarily mechanized and designed to operate in concert with its accompanying armor. These infantry formations are not generally equipped, trained, or preprepared to operate in more independent or leading roles. Additionally, for an ABCT with only four rifle companies, each dismounting just eighty-one riflemen, it is easy to see a scenario in which the brigade’s advance is quickly tied to the constant commitment and likely subsequent exhaustion and increased casualty rate of just 324 soldiers. All the while, the ABCT remains stuck on an adversary’s defense—with its large sustainment and maintenance nodes placed close enough to fuel, feed, and regenerate the formation—exposed to robust adversary precision-strike complexes. This consequently risks denying the division employing the ABCT a formation able to conduct any breakout operation, even if a penetration is achieved, and jeopardizes the division’s overall mission.

In contrast, a mobile infantry or Stryker brigade combat team, supported by some mobile protected firepower capability, would mitigate much of the aforementioned problem. Each of the brigade’s nine rifle companies dismount 108 riflemen, with organic weapons squads and mortar sections. This offers, for example, a severe dismounted infantry overmatch against infantry-short Russian tank-heavy battalion tactical groups, tank regiments, and combined arms brigades, and even against mechanized and motorized infantry-heavy formations. Moreover, their reduced sustainment requirements would diminish the demand for rear-echelon assets as well as supporting division and corps capabilities—to say nothing of the rapidity with which a mobile infantry or Stryker brigade can be moved strategic distances into theater compared to armor units.

Of course, some may argue that any reduction of armored vehicles on the battlefield would simply transfer the wrath of ferocious precision-strike complexes toward more vulnerable dismounted infantrymen. But the reality is more complicated due to three key factors. The first is the degree to which such complexes are tied to the use of UAS whose current battlefield dominance, particularly in Ukraine, seems heavily dependent on belligerent UAS magazine depth and investment in capabilities and strategies to penetrate opposing counter-UAS networks, the static and attritional nature of the front, and ongoing artillery and artillery ammunition shortages. The second is the ability of infantry formations within mobile infantry and Stryker brigade combat teams to utilize their organic vehicular transport to stage at distance from the front lines and move forward into adversarial strike range only when demanded, without the massive sustainment apparatus accompanying an armored brigade. And the third is the regularity with which dismounted infantry are able to disappear within existing or rapidly created restricted terrain, as demonstrated by the immense amounts of firepower required by both Ukrainian and Russian forces to advance against even small numbers of infantry, who prove extremely hard to dislodge. The firepower required to do so is subsequently exposed and targetable by supporting brigade, division, and even corps enablers.

Similarly, the belief that such a tactic would expose these formations to defeat from counterattacking armored elements or advance at too slow a pace to be of relevance are countered by a combination of historical evidence and analysis. After all, the exact characteristics of the terrain and battlefield that would constrain armor usage and encourage a tactical approach centered around dismounted infantry would naturally equally constrain an adversary’s use of armor, which would become vulnerable to a host of brigade antiarmor systems. This is especially so considering recent and continuing up-gunning of Stryker and mobile infantry brigade combat team antitank capabilities. Furthermore, despite common perception and training focus, the chief causal factor of tank loss has been both highly variable throughout history and inclining to greater democratization across the modern combined arms team. At the same time, it is a historical norm that restrictive terrain and the battlefield characteristics of a prepared defense work to slow the advance of formations regardless of mechanization to a pace well within the capacity of primarily dismounted infantry units to achieve. Most importantly, this preserves the combat effectiveness of a formation more prepared to achieve the rapid rates of advance associated with exploitations and pursuits: an armored brigade combat team.

As the largest sustained conventional conflict in the twenty-first century, the war in Ukraine will continue to draw much attention as the Army pursues its modernization strategy—in particular, the 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive, which saw a Western-trained and -equipped force struggle to utilize traditional Western mechanized-centric concepts of operations to penetrate a prepared defense. Yet such observations must proceed with a degree of caution. For while modern battlefield characteristics have certainly increased the penetration challenge, it would be incorrect to assume that this does not follow a known historical pattern of difficulty and costly operations, particularly for armored formations.

Fortuitously, however, just as history offers a warning, it also reveals a solution: When armor is unable to exploit its shock, firepower, and mobility en masse due to severely restricted terrain, the difficulty of the defense, or lack of support, go smaller. Lead with infantry, reconnaissance, or unmanned systems supported by small tank formations to set conditions before unleashing a trailing armored horde. The challenge facing commanders today is to properly identify governing battlefield conditions that force a transition in operational concepts as well as how to organize, train, and equip their formations to retain the flexibility to do so.

Captain Joshua Ratta is an armor officer who currently serves as the commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Troop, 1st Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Irwin, California. Hi previous assignments include commander of Bravo Troop, 1/11 ACR, tank platoon leader, distribution platoon leader, tank company executive officer, and battalion maintenance officer with 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team at Fort Carson, Colorado.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: armyinform.com.ua