The Army is losing exactly the kind of artificial intelligence talent it insists it needs to win the next war. Only four of the seven Army Artificial Intelligence Scholars recently considered for on-time promotion to major were selected. That sub-60 percent promotion rate stands in sharp contrast to a population in which more than 80 percent of captains normally promote on time, with additional officers selected early. Not one of these scholars, nor any of the thirteen in the year group immediately behind them, was selected early. The three officers the Army declined to promote were not marginal performers: Collectively educated at West Point, Princeton, MIT, and Carnegie Mellon, one was among only three officers selected in 2021 for the program’s most technically rigorous track.

In practical terms, the Army chose not to promote officers—barely three years after finishing graduate school—in whom it had invested more than $350,000 each (counting tuition and the cost of pay and benefits while in school). In its first measurable test, the Army’s flagship AI talent pipeline produced worse promotion outcomes than the force at large, despite drawing some of the service’s most academically and technically competitive officers.

I’m writing this as a supporter and alumnus of the program; I believe in its potential to deliver an AI-capable force. Absent immediate changes, however, it faces a predictable future: hemorrhaging the Army’s technical talent, gaining a reputation as a career killer, and becoming impossible to recruit for. The AI Scholars program is structurally misaligned with Army promotion systems, and that misalignment produces attrition as worrying as it is predictable. The Army can take steps to fix the problem immediately—without new authorities or legislation—but the clock is ticking. The next promotion board convenes on January 21, 2026 and will consider thirteen additional scholars.

What Is the AI Scholars Program?

The AI Scholars program, launched in 2019, is designed to fuse officers’ tactical experience with advanced training in machine learning and data science to produce dual-domain experts who can tackle the Army’s hardest modernization challenges. Highly competitive officers earn a two-year graduate degree at a leading technical university—primarily Carnegie Mellon—followed by a two-year utilization tour at the Army’s Artificial Intelligence Integration Center (AI2C), where they build AI models, applications, and data infrastructure for stakeholders across the force.

Although the annual cohort is small—roughly twenty officers—the program’s impact compounds over time. Scholars commit to at least five years of service after graduating, meaning the Army will have over a hundred AI Scholars in uniform at any given moment, forming the core cadre from which future AI leaders and larger talent-development efforts will be built.

Structurally, this mirrors other elite Army scholar programs and fellowships, such as the Olmsted Scholar Program, the Downing Scholarship, and the Harvard Strategist Program. On paper, the model is sound. In practice, promotion outcomes reveal a system fundamentally misaligned with Army promotion timelines and evaluation structures.

What’s the Problem?

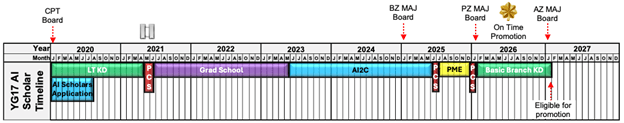

One key difference causes the traditional scholarship model to break down when applied to AI Scholars. All other programs select senior captains or junior majors who have already completed professional military education (PME), served in key developmental (KD) roles, and accumulated strong evaluations—in other words, they have checked the boxes necessary for promotion to major. The AI Scholars program does the opposite, deliberately targeting senior first lieutenants and junior captains who have not yet passed these gates.

There are rational reasons for this. Younger officers retain more technical fluency from their undergraduate degrees, have more runway to serve in technical roles, and represent a larger pool of potential applicants. But the Army’s career timeline is brutally unforgiving.

A typical officer pins captain four years after commissioning, then has roughly six years before pinning major. But officers must complete PME and KD in time for consideration by the promotion board, roughly four and a half years after pinning captain. PME takes six months, while KD requires at least twelve months—and eighteen to twenty-four is strongly preferred.

The AI Scholars program consumes four years by itself: two in school and two in utilization. Add PME and KD, and you now have five and a half years (minimum) of mandatory milestones crammed into a four-and-a-half-year window, and this does not account for geographic moves, administrative delays, course availability, or the inevitable dead time in real units—spent waiting for or transitioning into KD assignments.

In response to this mismatch, Army career managers point to two options: changing career fields or voluntarily deferring promotion. In practice, these are not genuine choices but pressure-driven exit strategies, each carrying its own penalty.

Many AI Scholars change career tracks under duress because their basic branches do not count AI2C time as KD, forcing them into new fields based on bureaucratic requirements rather than interest or aptitude.

Promotion deferral is presented as an alternative, but the suggestion is more coercive than constructive: Defer voluntarily or risk punitive nonselection and arrive at the same outcome.

None of this is disclosed to applicants. In fact, the application explicitly requires officers to attest that they will not change career fields during the program—an ironic contrast to the reality that this later becomes the primary means of avoiding career penalty.

Even if AI Scholars manage to navigate the timeline and avoid these forced choices, they still face a structural disadvantage: the rating pool at AI2C.

Promotion to major typically requires at least three “Most Qualified” (MQ) evaluations, ideally including one from a KD assignment. But upon graduating from Carnegie Mellon, all AI Scholars report to AI2C—meaning they all compete for the same fixed pool of MQ ratings. By regulation, senior raters may award MQ to no more than 50 percent of their rated population.

After completing the academic portion of other Army scholarship programs, graduates disperse into unique roles and become one of one in their rating pools. AI Scholars, by contrast, are placed into a cluster of high-performing technical officers where half must be rated “Highly Qualified” (HQ). An HQ rating may sound flattering, but it literally means that you have below-average potential relative to peers—an assessment promotion boards take at face value.

This is a known challenge in talent-dense organizations. However, two dynamics make AI2C even more punishing than other elite units like the 75th Ranger Regiment.

First, program timing leaves AI Scholars up for promotion with thinner and riskier evaluation records than peers. Captains arriving at the 75th already have multiple evaluations, including command reports, and many have already been selected for major before they are evaluated alongside fellow Rangers. AI Scholars, by contrast, arrive at AI2C with two unrated years from graduate school. Their first, and sometimes only, captain evaluations come from AI2C, so every HQ lands directly at the top of their primary promotion files.

Second, AI2C offers no structural flexibility in officer ratings. Senior raters across the Army can manage evaluation profiles by awarding HQ ratings to officers in low-stakes staff roles, saving MQs for commanders, or by assigning HQ ratings to officers who are exiting the service. None of those levers exist at AI2C. Every AI Scholar occupies the same rating category and is carried to the promotion board by the program’s service obligation, leaving no mechanism to distribute MQs strategically.

The result is a self-cannibalizing rating ecosystem in which the Army’s most technical officers enter their promotion boards with artificially depressed records.

What Are the Consequences?

These structural failures are already visible in the program’s outcomes. The 40 percent promotion failure rate for the first cohort is not a statistical anomaly. It is the predictable consequence of a flawed design.

Worse, the Army cannot simply find more AI Scholars. Even filling the annual quota has proven difficult. In my cohort, the Army nominated twenty candidates; Carnegie Mellon rejected twelve as academically noncompetitive. The program’s most technical track was designed to accept ten AI Scholars per year. In 2021, it admitted only three. The Army has just failed to promote one of them.

Beginning in 2027, the Army will confront the consequences of how it has managed its AI talent as AI Scholars’ service obligations begin to expire. They will be eight to ten years from retirement—too far to stay solely for a pension—and their decision to remain will hinge on whether they believe in the mission and whether they believe the Army has treated them fairly.

For those who feel frustrated, underutilized, or forced into suboptimal career fields, the alternative to continued service is attractive. In 2024, the median starting salary for graduates of a Carnegie Mellon program attended by AI Scholars was $150,000, excluding equity and bonuses, with top employers including Apple, NVIDIA, and Amazon. That figure does not account for the value of an active security clearance, which all officers have. If the Army cannot retain this talent, it may be forced to buy it back at two to three times the cost.

But the deeper loss is not financial. The Army is uniquely positioned to develop and sustain hybrid tactical-technical expertise. Every AI Scholar who departs or is forced to shift into a functional area represents one fewer dual-domain expert in AI and infantry, logistics, field artillery, intelligence, or sustainment. At AI2C, I saw firsthand that infantry officers built the best infantry tools, logisticians built the best logistics tools, and intelligence officers built the best intelligence tools. When branches lose technical officers, they do not just lose coding capability—they lose the people who can build the right tools, informed by lived operational experience.

A modernizing Army cannot afford that loss. Yet the system virtually guarantees it.

Patching the Program Before It Crashes: Three Immediate Fixes

Calls for talent-management reform are not new, and the full problem set is complex. But the Army can implement several high-impact corrections immediately, using authorities it already possesses. Taken together, these recommendations could help anchor the Army’s response to the Department of Defense’s recent directive on AI hiring and talent development.

1. Fix the Timeline

The Army should minimize predictable timeline friction from PME. A six-month PME requirement inserted after utilization—often requiring multiple relocations—can consume the narrow window available for KD and push AI Scholars toward career decisions driven by administrative convenience rather than professional fit. Two mitigations are straightforward: Expand the program timeline and send selectees to PME before graduate school, or deliver PME remotely, completing any branch-specific or in-person requirements during the summer between graduate school years. The remote option eliminates an additional cross-country relocation.

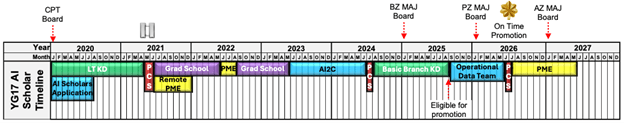

Utilization at AI2C should likewise be flexible, following the example of the Goodpaster Scholars, which allows officers to complete academic training, utilization, and command in nonlinear order without penalty. A default two-year tour is reasonable, but the Army must formalize the option to curtail or interrupt that tour so officers can complete KD time and remain competitive for promotion. One simple model would be:

- Year 1 (Development): Serve at AI2C to receive mentorship and transition from academic training to an operational engineering environment.

- Year 2 (Flexibility): Remain at AI2C, move to a KD assignment, or take a technical billet elsewhere (e.g., operational data teams).

I was allowed to follow this model, completing a one-year utilization tour that enabled a timely return to KD assignments and preserved promotion competitiveness in my basic branch. Most scholars are not afforded that flexibility.

A more aggressive alternative would place the entire utilization tour after KD time. Either approach addresses two problems at once: It allows officers to meet KD requirements and shifts their key evaluations into less structurally punitive rating pools. In doing so, it also aligns incentives appropriately—AI2C would retain scholars by offering compelling work and strong professional development, rather than by default assignment.

2. Build Ownership of the Problem

These structural fixes will fail without ownership. Branches remain essential stakeholders but are poorly positioned to manage officers in the AI Scholars program. Branch career managers are responsible for hundreds of officers but encounter only one or two AI Scholars at a time and lack visibility into the program as a whole. Branch-specific PME and KD rules further complicate management, creating a patchwork of requirements that undermines consistent, program-level decision-making. As a result, AI Scholars receive inconsistent, branch-specific guidance rather than deliberate program-level management.

AI2C previously had a lieutenant colonel dedicated to talent management who partially mitigated this problem by advocating for AI Scholars and deconflicting timelines. That position sat vacant for a year, which coincided with key career decisions by the nonselected officers. The center has likewise gone over a year without a permanent director, signaling limited institutional priority for a program billed as strategically vital.

3. Build a Real Home for AI Talent—Without Isolating It

Six years after the AI Scholars program began, the Army has created a formal AI officer career track. While this is a better-late-than-never step in the right direction, the track’s ultimate success will depend on being resourced, populated, and empowered to function as a true professional home for AI talent.

More importantly, concentrating all AI talent in a single functional area would be a mistake. Dual-domain officers are most valuable when they remain anchored in their basic branches. At AI2C, infantry scholars drove the best infantry solutions because they had personally experienced the problems they were trying to solve. They were building tools for the soldiers and noncommissioned officers they had led—and would lead again—and for themselves.

The Army’s logistics branch has already shown what right looks like. Under Lieutenant General Michelle Donahue, the branch rewrote its career model so that data-engineer and data-analyst roles count as KD from captain through lieutenant colonel. That single change allowed logistics to poach two AI Scholars—a Sapper-qualified engineer and a Ranger-qualified infantryman—and convert them into logisticians who will spend the next decade building AI-enabled systems for their new branch.

If there is a war for talent, the logisticians are winning. Every branch should be fighting just as hard.

4. Use New Promotion Authorities Where They Are Most Needed

The Army’s new adaptive promotion model allows officers in multiple year groups to be considered for promotion (under the up-or-out system, consideration is limited to a single year group) based on mission needs and demonstrated potential—not just time in grade. The first pilot is in the Medical and Dental Corps, to retain physicians and dentists whose training disrupts standard timelines.

The Army’s own release notes that this program could be expanded to fields like software development, AI, and robotics, where “traditional promotion timelines can limit agile management of rapidly evolving expertise.”

This expansion should begin immediately. If the Army can create flexible promotion windows to retain dentists, it can do the same for its strategically vital cohort of AI experts.

The Cost of Doing Nothing

While I was writing this, the Department of Defense unveiled GenAI.mil, its new enterprise generative AI platform. The timing is ironic. The memo announcing the platform declared, “Victory belongs to those who embrace real innovation”—one week after the Army failed to promote three officers who had done exactly that. Two years before GenAI.mil launched, AI Scholars built and launched CamoGPT, a secure generative AI system widely used across the joint force.

The department is celebrating an AI milestone while the Army loses the very officers who make breakthroughs like it possible. This is symptomatic of a system that publicly celebrates innovation while structurally penalizing its innovators.

If the Army wants an AI-enabled force, it must decide whether innovation is a career risk—or a path it is willing to reward.

Captain Nathaniel Fairbank was part of the second cohort of Artificial Intelligence Scholars and built CamoGPT while serving at the AI2C. He is currently a rifle company commander in the 25th Infantry Division.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Spc. Micah Wilson, US Army