The United States Army’s ability to deliver precision fires and effects is fundamentally tied to its doctrinal targeting methodology: decide, detect, deliver, assess (D3A). Field Manual 3-60, Army Targeting prescribes the use of D3A as an integrative approach requiring cooperation across multiple warfighting functions. As the Army advances under the pressures of multidomain operations as its operational concept, optimizes its contributions to US strategic competition with near-peer adversaries, and pursues its recently announced transformation initiative, the necessity of integrating artificial intelligence into targeting workflows is paramount.

AI technologies have already proven their utility across a range of defense applications, including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance processing, decision support, and autonomous systems operations. Over the past several years, a growing body of academic research has explored these capabilities, yielding insights with significant implications for military policy and doctrine. Key takeaways from this body of work include:

- AI in targeting presents a moral dilemma—it must be employed as a tool, not as a substitute for the warfighter’s judgment.

- Time is the most compelling performance metric for evaluating AI effectiveness in the targeting process.

- AI offers undeniable scaling advantages, particularly in data processing and decision acceleration.

- Human commanders must remain the final arbiters of lethal force, preserving the principle of human-on-the-loop decision-making.

- AI should augment—not replace—critical targeting functions, such as rules of engagement validation, proportionality assessments, and determinations of military necessity.

Even with these insights established by research, AI’s integration into the D3A targeting methodology remains underdeveloped in operational doctrine. There is therefore a central question the Army has yet to answer: Can AI enable the D3A cycle to achieve faster, more reliable, and more effective targeting—while preserving accountability through human oversight?

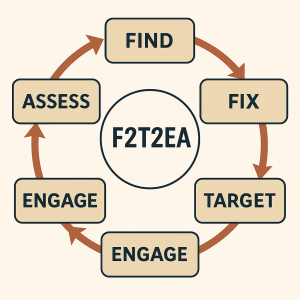

Emerging programs such as the Israeli AI-enabled system known as “the Gospel,” the US Department of Defense’s Project Maven, and other kill chain automation initiatives reflect a growing desire to accelerate targeting cycles. These efforts are largely aligned with the F2T2EA (find, fix, track, target, engage, assess) model used in joint targeting. The Army, however, continues to rely on D3A as the doctrinal cornerstone of fires and effects integration at the brigade and division levels. To adapt AI to the D3A methodology, a modular and doctrinally grounded approach is required—one that maps AI capabilities to discrete phases of the targeting cycle and identifies value-added contributions to each step.

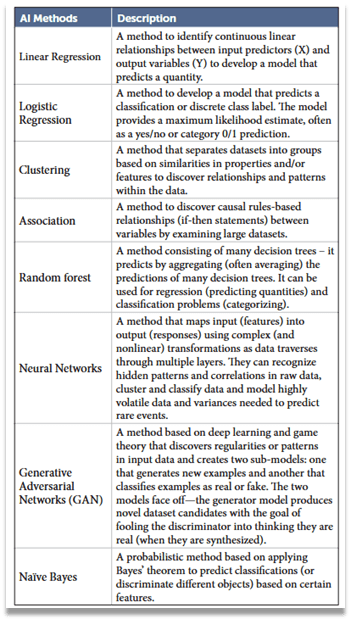

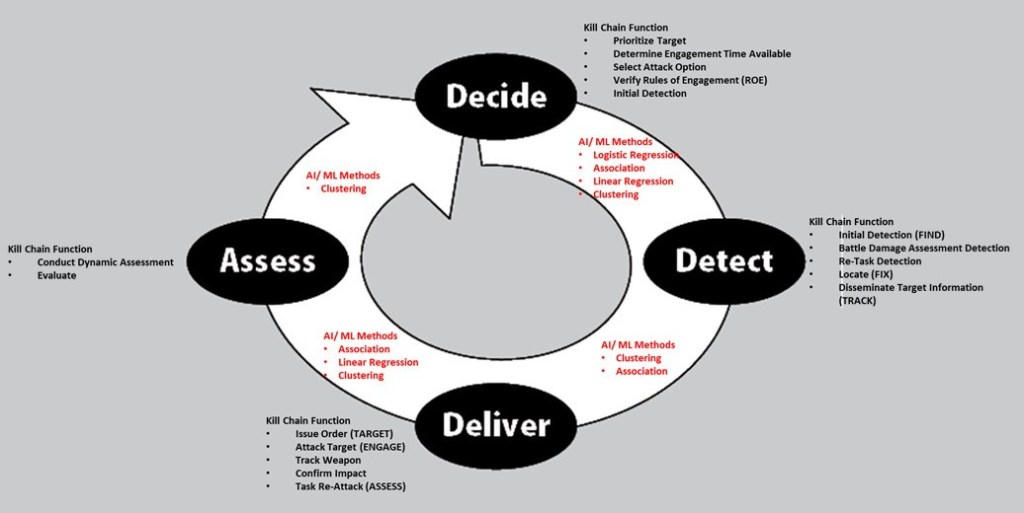

Building on a recent study in the Naval Engineers Journal, which mapped AI methods to F2T2EA kill chain functions, we can extrapolate AI applications for each phase of D3A. In the decide phase, tools such as game theory models, decision trees, and logistic regression algorithms can support enemy course-of-action development, attack asset prioritization, and effects determination. During detect, AI excels at target recognition via pattern association and anomaly detection, leveraging sensor fusion and deep learning. This will greatly reduce the time it takes to determine a target’s functional characterization, especially at large scales. For deliver, optimization algorithms and prescriptive analytics can refine weapon-target pairing and target engagement timings. This has the potential to eliminate human-introduced error in the target vetting process. Finally, in the assess phase, battle damage estimation benefits from clustering models and explainable AI tools that support image interpretation and effects validation. Along with correlation modeling this can bring greater transparency to the combat assessment process, saving precious time and munitions as well as bringing greater clarity to the commander’s decision support tools.

The study published in the Naval Engineers Journal examined eight specific AI methods relevant to targeting, using empirical methods of analysis. These included logistic regression, linear regression, clustering, association rule learning, and several others. However, not all methods proved suitable for targeting. Random forest and generative adversarial networks were dismissed for their black-box characteristic—when tasked with justifying and rationalizing their targeting solutions, these systems were incapable of explanation. This is not just a technical problem but, more importantly, a legal showstopper. As those familiar with theater rules of engagement and the law of armed conflict know, commanders are directly responsible for ensuring compliance with the tenets of military necessity and proportionality when conducting targeting operations. Under these circumstances, black-box systems are a liability rather than an asset. Moreover, AI methods like advanced neural networks, while promising for other applications, require vast and labeled datasets—often unavailable in tactical contexts. Naïve Bayes methods were also rejected as unsuitable. They exhibited a tendency to assume independent values between variables such as speed, altitude, and heading—an untenable simplification in target analysis. Ultimately, while these methods expedited the mechanics of targeting workflows they failed to capture a critical function: AI-enabled targeting doctrine must codify decision points where human intervention is not just preferred—but required.

While DoD experimentation exercises like Project Convergence are eager to showcase the application of AI technologies, these technologies are not without limitations. For example, current large language models (LLMs), such as Meta’s LLaMA, can present a unique risk: They operate via statistical prediction without true comprehension of doctrinal terminology or contextual nuance. If we were to prompt a commercial, off-the-shelf LLM on how to destroy a particular target, this type of AI would not inherently grasp the human understanding of the concept. Believe it or not the targeting effect destroy is a complex notion, one filled with contextual relations. Achieving the effect destroy beyond simply physical damage also has a time component. Destroy also means ensuring the target cannot fulfill its primary function for the remainder of a mission. Such comprehensive understanding requires structured LLM training on doctrinal lexicons, rules-based decision trees, and munitions modeling—all things that are not in these generalist models.

At a fundamental level, incorporating AI into D3A is about optimizing the targeting workflow. In multidomain operations, accelerating sensor-to-shooter kill chains, reducing cognitive burden, and improving commanders’ decision-making in contested environments is the goal. By embedding AI where it adds the most value, and ensuring humans remain central at key decision points, the Army can modernize its targeting process while honoring its moral and legal responsibilities. In doing so, it can ensure that D3A remains both fast and just, anchored in human judgment, yet elevated by intelligent machines.

Jesse R. Crifasi is a retired US Army chief warrant officer 4, former division artillery targeting and division field artillery intelligence officer for the 82nd Airborne Division. He is a senior advisor in the defense industry specializing in joint fires and targeting, and a PhD student in public policy and national security at Liberty University. He has authored multiple doctrinal and technical assessments on digital fires and artificial intelligence integration in targeting operations.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Sgt. Rebecca Watkins, US Army