Buckle up: This piece is going to get wonky. For those readers who particularly enjoy the minutiae of Army organizational structures, you’re welcome. For the rest of you, please accept our apologies—but since this issue affects vastly more people in the Army than are engaged on the topic, we hope you’ll stick with us. After all, it’s only 1,400 words.

If we’ve learned one thing from the Army Transformation Initiative (ATI) and the recent Army Structure (ARSTRUC) memorandum for 2028–2032, it’s that the Army recognizes it needs rapid, organizational change to meet the challenges posed by the modern battlefield. If we’ve learned a second thing, it’s also that the Army is in fact capable of this change. Units represented by what are known as MTOEs (modified tables of organizational equipment)—the vast majority of the operating force—will likely soon look nothing like they did fifteen, ten, or even five years ago. But one set of organizations left behind by all of the restructuring and modernizing efforts seems to be those operating under a different model of apportioning personnel and equipment—the TDA (table of distribution and allowances).

To put it bluntly, TDA organizations are weird—almost inexplicably so. They reflect their evolutionary and piecemeal design and redesign, with bits and bobs bolted on, ultimately taking on a Frankenstein’s monster structure all their own. It is invariably shocking when those who have grown up in brigade combat teams in the operating force arrive at a TDA organization, likely still called a brigade, and find key position grade plate differences or even entire staff sections completely absent. Even TDA organizations with the same mission set (e.g., the 197th and 198th Infantry Brigades at Fort Benning, Georgia, responsible for training 11B infantrymen and 11C indirect fire infantrymen, respectively) do not have the same structure. How we got to this mashup is mildly interesting, but where those structural changes are going will be critical.

The Current Situation

TDA organizations are generally found in the Army’s generating force. They facilitate recruiting, training, and equipping units in the operating force, with many such organizations falling under the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC, which, per the ARSTRUC, is about to combine with Army Futures Command to become Transformation and Training Command, or T2COM). Given the emphasis on transformation, it’s prudent to ask how these organizations in the generating force are changing to support the ATI and ARSTRUC in preparation for large-scale combat operations. The answer seems to be: They aren’t. One reason for this is the cumbersome and byzantine way in which TDA structures change in the first place.

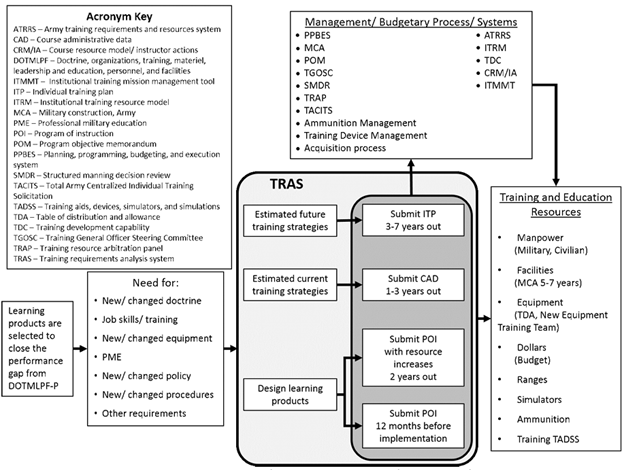

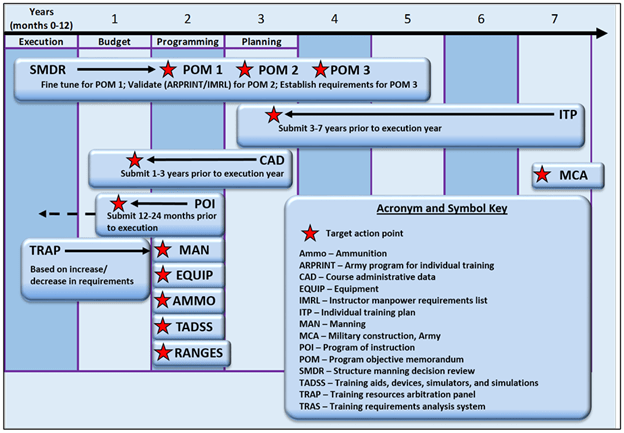

Simply put, our current operating environment is moving faster than either the program objective memorandum model or the Training Requirements Analysis System (TRAS) can support. To understand the constraints, it’s helpful to look at the existing resourcing processes within the TRADOC enterprise. The TRAS, by design, is a three-to-seven-year process. It is also heavily dependent on several other processes and boards to validate and resource training. (See figures below.)

The TDA is wrapped up under the TRAS and is influenced, as shown in the figures above, by an alphabet soup of mechanisms—the CRM/IA (course resource model / instructor actions), IMRL (instructor manpower requirements list), ITRM (institutional training resource model), SMDR (structured manning decision review), TRAP (training resource arbitration panel, POM (program objective memorandum, already mentioned), and others. These models and systems all have an influence on the TDA.

The TRAS is a complex and methodical process that doesn’t lend itself to rapid change. That’s not to be said that this wasn’t, at one time, the appropriate model for training resource management. But a cycle that takes the tenures of between two and four commanders to realize change is not acceptable given the needed pace of change exemplified by the operating force.

A Way Forward

As ATI and ARSTRUC have shown us, the byzantine processes of the Army optimized over the course of nearly two decades of post-9/11 wars need not remain sacrosanct in a new era with very different operational and strategic imperatives. One potential solution, which is in keeping with the ATI drive to innovate at the lower levels, would be to enable commanders of the Army’s centers of excellence more leeway to drive the change in their organizations. It can and should be these commanders’ prerogative to identify and direct changes to the TDA organizations within their centers of excellence to best support the coming ATI and ARSTRUC changes in the operating force. This can begin with an internal look at how the TDAs are structured to deliver results now, not just in the context of, for instance, SMDR projections into the future. Even if the directed changes are temporary and require later codification through the normal process or revalidation by subsequent commanders, this would allow the centers of excellence to react more swiftly to circumstances, take necessary risks, and increase creative problem solving and experimentation.

It would also enable TDA changes to be trialed and more rapidly nest with change in the operating force rather than perpetually lagging because changes have been based on analysis that is outdated within a single fiscal year, let alone the multiple fiscal years that current processes require for changes to take place. If ranks need to be adjusted, adjust them. If paragraphs and line numbers aren’t aligned with the way an element actually trains, realign them. If property needs to be centralized or decentralized, just execute the changes.

Additionally, there needs to be much less adherence to structure for structure’s sake. We should not waste mental energy trying to conform the structure of today to the needs of tomorrow if they are not clearly fit for that purpose. That means we must be willing to embrace entire headquarters realignment on installations if warranted. This is also happening with the merger of Army Futures Command and TRADOC, but it cannot stop there. If the operating force can shed its attachment to the old brigade combat team structure for the sake of transformation, then so should the generating force be able to examine and adapt its own organizations.

Finally, we must more broadly accept the importance of generating force billets in our officer career progression. Generating force company-level commands are too often perceived as a dumping ground for those who couldn’t cut it in the operating force. But if we continue to assume risk with the managers of the proverbial seed corn, our harvest will be that much worse for it. All branches should prioritize their initial entry training company/troop/battery commands, whether as key developmental jobs or broadening assignments on par with assignments as observer controller/trainers at the Army’s combat training centers, to better develop officers who can speak intelligently about the whole Army and understand where their soldiers come from. The emphasis placed by the noncommissioned officer corps on the position of drill sergeant must be similarly replicated by the officer side.

All That is to Say . . .

This is a complex issue, likely even more so than articulated in the 1,400 words above (we promised we’d keep it short). But whether the true underlying issue is the program objective memorandum, the TRAS, or some other cyclical process, the time is now for the center of excellence commanders to be empowered to act more aggressively and with greater discretion to simply change their respective subordinate TDA organizations to meet the needs of the transforming operating force. This can and must occur, regardless of what staff calculations and bureaucratic processes say, to truly generate continuous transformation in the Army. ATI and ARSTRUC have set the Army on a change trajectory, which increases in velocity each day. The generating force must keep up lest we fail to produce the soldiers and leaders the operating force will need to fight and win the next war.

Lieutenant Colonel Scott Dawe is an armor officer and currently commander of 5th Squadron, 15th Cavalry Regiment (19D one-station unit training) in the 194th Armored Brigade, Maneuver Center of Excellence, Fort Benning Georgia.

Retired Sgt. 1st Class David Neuzil is a former 19D scout and is currently the GS-13 lead training developer for the 194th Armored Brigade, Maneuver Center of Excellence, Fort Benning Georgia.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Patrick A. Albright, US Army