On July 24, 2024, US F-16 and F-35 pilots scrambled to intercept a combined formation of two Chinese H-6K and two Russian Tu-95MS bombers as they entered the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone—a first-of-its-kind combined operation for Beijing and Moscow. For Washington, the message was clear: China’s military diplomacy is no longer confined to its backyard. This was not an isolated stunt, but the product of years of steadily growing international military cooperation cultivated through the execution of combined exercises with foreign forces.

Over the last eight years, Beijing has more than doubled its participation in such exercises, concentrating on partners in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and select Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) states. While China still trails the United States in the scale and sophistication of its drills, the trajectory of its exercise growth suggests a long-term strategy to expand influence and challenge US dominance in Eurasia. Future growth in Chinese bilateral and multilateral exercises could significantly impact US interests. For example, deployment of Chinese military units to Iran for combined air defense exercises would have profound strategic impacts in the US Central Command area of responsibility. The United States must closely monitor these trends and posture accordingly to ensure that emerging patterns of Chinese foreign military cooperation do not translate into unchallenged strategic advantage.

China’s Expanding Exercise Profile

To analyze China’s expanding foreign military engagement, we extended a 2021 joint military exercise dataset compiled by Jordan Bernhardt to cover US and Chinese exercises from 2017 through 2024. Using the Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act library, LexisNexis, and official US and Chinese government press releases, the dataset extension captures 1,279 exercises involving 187 countries. The results underscore how rapidly Beijing has embraced combined exercises as a tool of influence, with much of this expansion concentrated within the SCO.

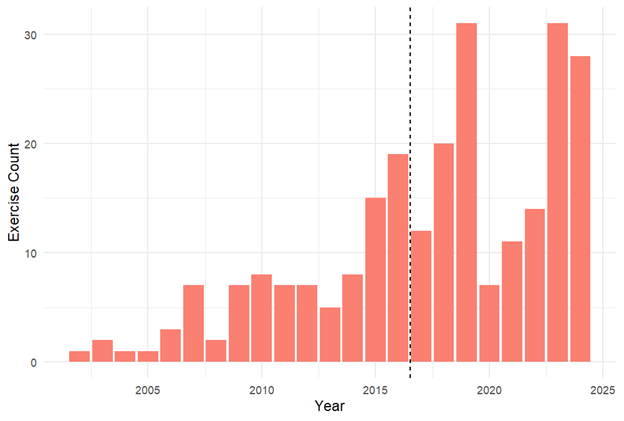

China’s growth in economic and military power has been mirrored by increased participation in international exercises. In the early 2000s, China participated in only one or two exercises per year. That figure rose to an average of 9.5 annually by 2009–2016, per Bernhardt’s dataset. Since 2017, the pace has more than doubled to 19.3 per year, an especially impressive increase considering the lull in international exercises caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. The trajectory is unmistakable: China is deliberately normalizing its military presence abroad.

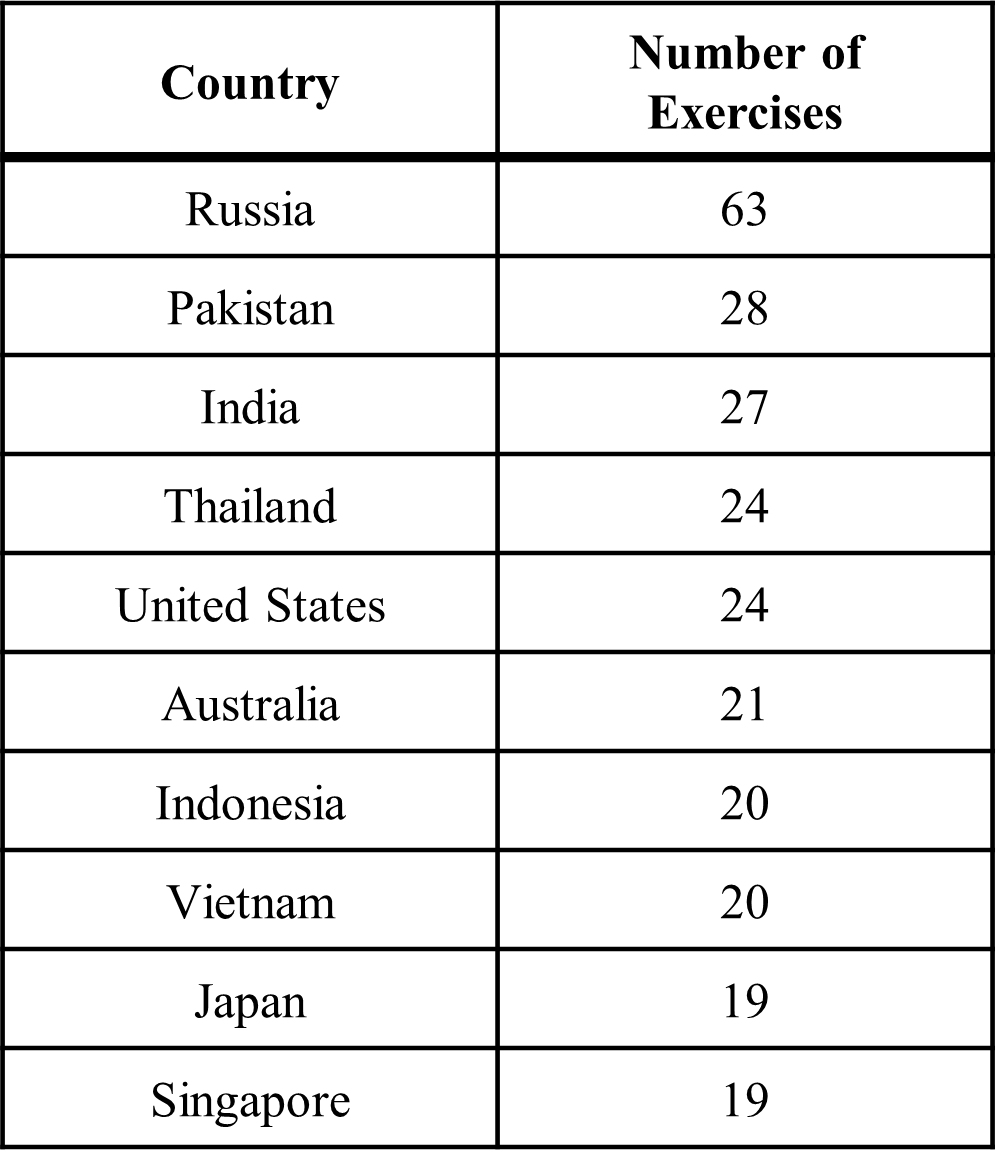

While China has made gains in the raw number of exercises its forces participate in, the scope of countries that they integrate with is still relatively limited compared to the breadth of partners the United States works with. Table 1 shows the top ten most frequent participants of exercises with China between 2017 and 2024. Russia is China’s most frequent exercise partner with sixty-three combined exercises conducted during this period. China’s two other most populous SCO partners, Pakistan and India, follow in second and third place, with Thailand occupying fourth.

Interestingly, China participated in twenty-four exercises with the United States, enough to tie for fourth among China’s overall exercise partners. Considering the strategic rivalry between these two states, this is very unexpected. There are two explanations: historical US integration efforts and participation in non-combat-oriented exercises.

In the 2010s, Washington invited Beijing into marquee multilateral events like Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) and Cobra Gold. China participated in RIMPAC in 2014 and 2016 before being disinvited in response to security concerns and Chinese militarization of South China Sea islands, but continued to join Cobra Gold through 2024, albeit with its participation confined to humanitarian aid and disaster relief roles. Beyond that, many shared events were multinational peacekeeping or survival training exercises, such as Mongolia’s Khaan Quest or Australia’s Kowari. Naval gatherings like Indonesia’s Komodo further padded the count without requiring true tactical integration.

China and the United States have a mutual interest in safeguarding information regarding military capabilities and tactics, techniques, and procedures from each other; despite combined exercise participation, the limited scope of these exercises demonstrates that neither country is interested in true military integration. Between 2017 and 2024, the United States conducted 1,143 exercises, underscoring its pervasive role in international military engagement. China’s relatively high exercise count with the United States says more about America’s hegemonic presence in global exercises than about China-US cooperation.

Why Combined Exercises Matter for China

Combined exercises are foundational to the establishment of effective security cooperation between states. They represent a distinct and strong form of alignment because they require the sharing of tactics, techniques, and procedures—creating a shared level of trust that is deeper than arms sales alone. Frequent exercises enhance interoperability, normalize deployments abroad, and foster habits of cooperation. For the United States, these serve as one of the bedrocks of its alliance system. For China, growing exercise participation signals its intent to develop a similar, if narrower, network of security partnerships.

SCO Partnerships: The Core of Chinese Engagement

Excluding US-linked drills reveals the extent of the SCO’s dominance within China’s exercise portfolio. Nearly half (68 of 154) of China’s combined exercises involved SCO partners. In addition, SCO members make up seven of China’s top ten exercise partners.

Founded in 2001, the SCO originated as a forum to settle cross-border disputes between its original partners: China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. It has since added India, Pakistan, Iran, and Belarus, and its member states now account for over 42 percent of the world’s population and 23 percent of global GDP. It has also expanded its policy purview to cover a wide range of economic and security cooperation initiatives. The SCO’s recent growth has alarmed Western observers about its potential as an illiberal rival to the US-led order. That concern sharpened at the September 2025 Tianjin Summit, where SCO members agreed to institutionalize cooperation with the establishment of a new development bank and called for a new system of global governance. Against this backdrop, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has steadily expanded its combined exercises with SCO partners, using them as a proving ground for power projection.

Russia stands apart as China’s most important partner in combined military activity with fifty-two exercises during this period, including thirty-two bilateral drills. Most of these demonstrated power projection capabilities, such as the annual Joint Sea series of integrated naval exercises, which have ranged from the Western Pacific to the Baltic Sea. Since 2019, China and Russia have also conducted nine strategic aerial patrols, pairing bombers and support aircraft on routes that often pass near key US allies like Japan and South Korea. The eighth patrol, in July 2024, went further by piercing the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone over the Bering Sea, representing a significant posture escalation.

Pakistan’s second-place ranking is unsurprising given its status as the largest importer of Chinese arms. In its recent skirmishes with India, Pakistan has served as a proving ground for combat employment of modern Chinese weapons, including the J-10C fighter aircraft and PL-15 air-to-air missile. Its performance in these conflicts was likely enhanced by its participation in the Shaheen series of bilateral air combat exercises conducted with the PLA Air Force since 2011. Unlike Russia, however, Pakistan continues to maintain security ties with the United States and has executed several bilateral military engagements with US forces as well.

Similarly, India engages in exercises with both the United States and China. Its strategic alignment remains complex and has been a focal point of US foreign policy efforts. Notably, between 2017 and 2024, India participated in four times as many exclusive exercises with the United States as with China, including high-end warfighting exercises such as Red Flag – Alaska, RIMPAC, and Pitch Black. However, this relationship remains fluid and closer cooperation between New Delhi and Beijing is possible as SCO institutions continue to mature.

Despite having relatively small militaries, the original Central Asian members of the SCO remain some of China’s most prominent exercise partners. PLA forces conducted some of their first international exercises in these countries and continue to prioritize integration with them, primarily in SCO counterterrorism drills such as the Peace Mission series of exercises.

The only two SCO countries outside of China’s top ten are Iran and Belarus. This is largely due to these countries joining the SCO very recently—2023 for Iran and 2024 for Belarus. Nonetheless, each country participated in six non-US combined exercises with China between 2017 and 2024, tying them at thirteenth among Chinese exercise partners. Of note, Iran has participated in a series of annual trilateral naval exercises with China and Russia since 2019. With their recent addition to the SCO, it is likely that combined exercise participation levels between China, Iran, and Belarus will grow significantly.

Overall, the data shows that China is prioritizing engagement with its SCO partners to train its military in deployed settings and to serve as a foundation for executing power projection operations beyond its borders.

ASEAN Engagement: Competing for Influence in Southeast Asia

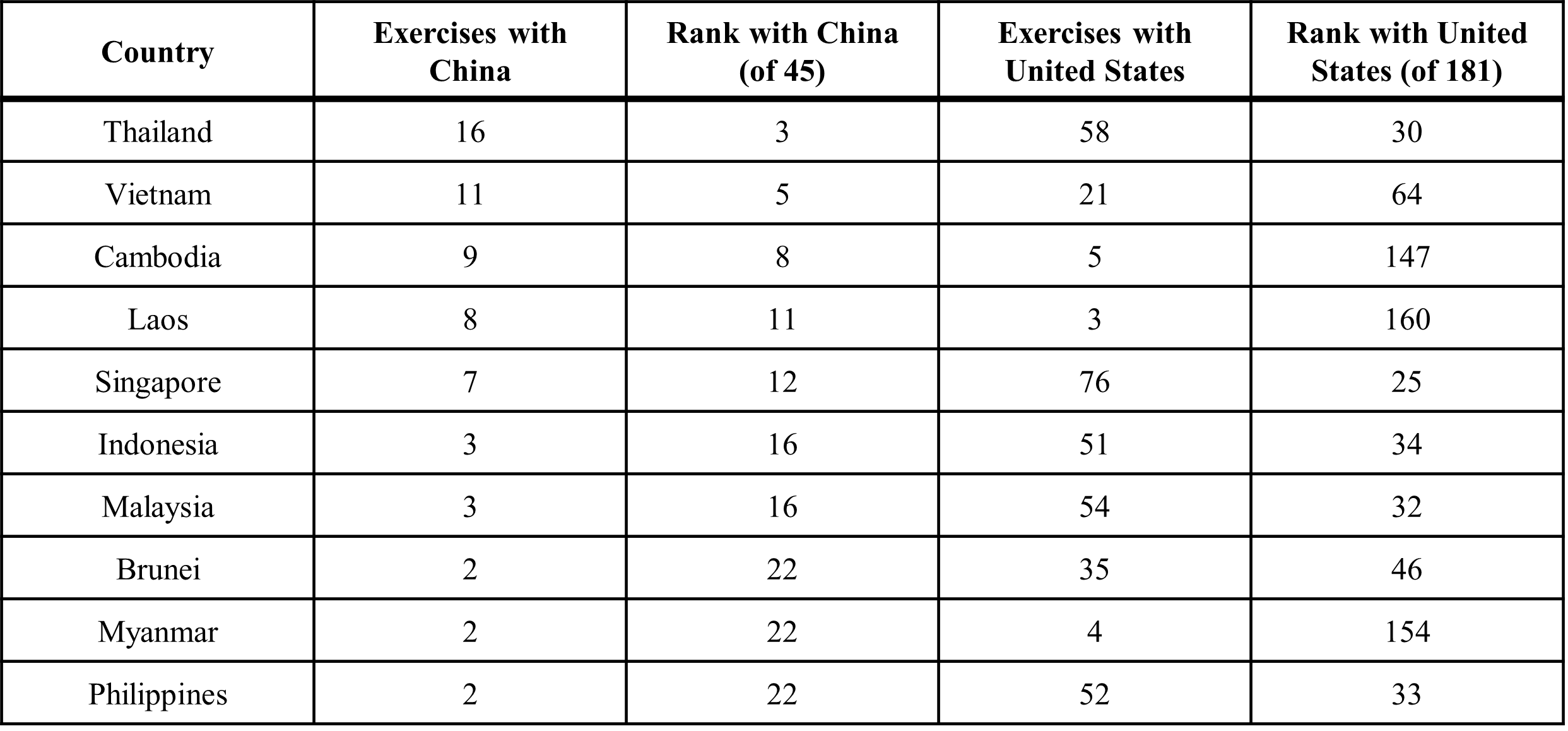

All three of the non-SCO countries in China’s top ten exercise partners are in Southeast Asia, a clear signal of China’s regional aims. Table 3 details each ASEAN country’s exclusive combined exercises with the two superpowers between 2017 and 2024. The most strategically significant exercise partner is Thailand, where closer military ties with China threaten a long-standing US partnership. The Cobra Gold series, hosted annually by the United States and Thailand, is the largest joint and combined exercise in the region dating back to 1982. This capstone-level exercise features warfighting integration across conventional and special operations capabilities. Chinese military presence in Thailand caused US military officials to warn Cobra Gold participants to expect Chinese agents to be filming and listening to all exercise activities as early as 2017. Deepening Chinese-Thai military cooperation casts doubt on the US-Thai relationship and provides an ideal venue for Chinese intelligence to exploit US tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Although exercises with Vietnam have increased, they are primarily combined border patrols and disaster relief exercises. These bilateral events are focused on preventing escalation along the border, not external power projection or warfighting integration. Increases in engagement in Cambodia and Laos are also concerning for US interests. Although both countries have limited military capabilities, sustained PLA involvement could expand China’s ability to counter US partners in the region.

For now, Chinese military activities with ASEAN states remain modest and trail behind those of the United States. However, closer cooperation between China and Thailand should give US planners pause. At what point does Chinese integration threaten US core objectives with military outreach, or signal diverging alignment to the point that the stability of US-Thai relations is threatened? An uptick in arms exports, talks of Chinese foreign basing opportunities, or storage of war reserve materiel in the region would also be concerning for US interests. Although the SCO appears to be China’s main focus for expansion of military partnerships, continued engagement throughout ASEAN may help illuminate China’s regional ambitions and the appetite of local players to engage.

Limited in Scope—So Far

Despite steady growth, China’s combined exercises remain limited in scope compared those of to the United States. China’s 154 exercises conducted with 45 countries pale in comparison to the US total of 1,143 exercises conducted with 181 partners between 2017 and 2024. Compared to US alliances and partnerships, PLA activities emphasize presence and signaling over true interoperability. Most exercises involve limited force packages, basic coordination, and scripted scenarios. Even with Russia, coordination has yet to reach the level of integrated command structures or combined operations typical of US exercises with its primary allies.

The greater significance lies in trajectory. By conducting regular exercises, China normalizes PLA deployments abroad, familiarizes itself with diverse operational environments, and develops habits of cooperation with foreign militaries. These trends lay the foundation for deeper collaboration should Beijing choose to pursue it.

How Should the US Government Respond?

China’s rapid expansion of combined military exercises since 2017 illustrates a deliberate effort to strengthen its security partnerships, particularly within the SCO. While China’s total number of exercises still lags behind that of the United States, the geographic and political concentration of its activities highlights Beijing’s strategic intent: building durable security relationships within the SCO and deepening relationships with strategically valuable ASEAN neighbors.

For now, most exercises remain limited in scope, often emphasizing counterterrorism or symbolic displays of cooperation rather than deep integration of tactics, techniques, and procedures. Even high-profile drills with Russia, including combined bomber patrols near US and allied airspace, appear more focused on signaling than on operational interoperability. However, increasing military outreach points to potential future concerns.

US security leaders should track not just the number but also the scope of Chinese exercises. This requires attention to changes in force composition, technological sophistication, and operational integration. It is critical to avoid overreacting when exercises remain small or symbolic. However, persistent, higher-end drills should trigger a reassessment of US posture and readiness. Significant PLA integration in future Russo-Belarussian Zapad exercises, for instance, would be an early indicator of a more assertive power projection posture. Another example would be the sale of advanced air defense systems to Iran, paired with combined exercises to optimize their employment. Careful, disciplined monitoring would ensure that the United States can respond proportionally and maintain credibility without overcommitting to minor provocations.

The United States must avoid retrenchment and sustain combined training and exercise programs with international partners, especially strategically important nations such as India and Thailand. Exercises should emphasize interoperability, rapid crisis response, and practical operational value, demonstrating to partners that US engagement provides tangible benefits compared to Chinese alternatives. In addition, exercises should not occur in isolation but be paired with diplomatic initiatives, economic incentives, and selective arms transfers to reinforce US influence across multiple domains. This approach signals a comprehensive and coherent strategy, highlighting reliability, long-term commitment, and multilateral cooperation.

If significant qualitative improvements in PLA capabilities are observed, the United States should scale up exercises and deployments in relevant regions to deny China uncontested influence. This includes close coordination with NATO and key regional allies to ensure that responses are unified, credible, and proportionate. A proactive posture would enable the United States to shape regional dynamics, reassure partners, and deter potential aggressive moves. For example, recent reports indicate Russia is training Chinese airborne forces. If these efforts continue to the point of demonstration during a combined exercise, the United States and its allies could answer by forward-deploying air defense units and executing their own exercises that specifically focus on intercepting hostile airlift, signaling that the capability would not go uncontested.

Ultimately, Chinese combined exercises matter less for their absolute numbers than for their trajectory. The SCO provides China with a ready-made platform to build habits of cooperation, normalize PLA deployments abroad, and strengthen an illiberal security network. For US forces, the challenge is twofold: careful monitoring to distinguish signaling from meaningful integration, and sustained partnership building from Southeast to Central Asia. With proactive engagement, the United States can ensure that China’s expanding military diplomacy does not credibly threaten US national security interests abroad.

Major Jane Kaufmann is an AC-130J weapons system officer with three combat deployments to Afghanistan. She recently graduated from Stanford University with a PhD in political science as a CSAF Scholar.

Lieutenant Commander Chris Pagenkopf is an F-35C pilot and TOPGUN graduate with multiple deployments in the Indo-Pacific and Mediterranean. He currently serves as a Fleet Scholar attending Stanford University in the master’s in international policy program.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense, or that of any organization the authors are affiliated with, including the Department of the Air Force and Department of the Navy.

Image credit: kremlin.ru, via Wikimedia Commons