In 1981, the Army created the National Training Center and gave it a critical task: to prepare units to “win the first fight.” Central to that task is an OPFOR—the opposition force—that presents rotational training units with realistic military problems. But doing so is a moving target. The perpetually changing character of warfare demands a dynamic opposition force capable of developments in technology and in tactics, techniques, and procedures. How is the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment “Blackhorse” adapting to meet that imperative? And what can units expect when they encounter Blackhorse OPFOR at the National Training Center?

A few months ago, Major Zackery Spear and Lieutenant Colonel Michael Culler took to the digital pages of the Modern War Institute to call for the US Army to adopt reconnaissance-strike battle as a tactical construct in order to properly implement multidomain operations, as well as for the Army’s combat training centers like the National Training Center (NTC) to create dedicated reconnaissance-strike complex formations to teach rotational training brigades how to survive and win in such an environment. At NTC, this is not some far-off imagined future, but an emerging cornerstone of how the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment gives units their worst day in the desert. It takes the form of the regiment’s Centaur Squadron—a purpose-built reconnaissance and security formation that combines legacy manned and new unmanned platforms to answer priority intelligence requirements, continually challenge brigade combat teams across all nine forms of contact, and preserve Blackhorse combat power for key periods of operations while attritting and shaping a brigade prior to main body contact.

Reconnaissance and Strike on the Modern Battlefield

Professional discussions about combat training centers typically focus on how difficult a rotation can be for training units. But making it difficult is itself immensely challenging for the OPFOR unit, which must ingest observations from real-world conflicts and incorporate them rapidly into its own operating procedures.

For the Blackhorse Regiment, successful reconnaissance and strike operations have long been key to allowing the OPFOR to continuously challenge a variety of rotational training units, despite possessing just 40 percent of an armored brigade combat team’s combat power. Yet, while the regiment’s division and brigade tactical groups may possess plenty of sensors and indirect fires assets, successful employment of such diverse capabilities has become increasingly difficult in light of several observed factors.

First, the modern challenge in warfare’s information dimension is not one of scarcity but of abundance, synchronization, and dissemination. As repeatedly observed, the combined array and availability of sensors has rendered the battlefield increasingly transparent—particularly in the open spaces of the Mojave Desert. However, achieving such transparency is often more difficult than initially presumed, for two reasons. The first is that such a diverse array of sensors must be properly synchronized and allocated to not only correctly orient on requisite named and targeted areas of interest but also ensure assets such as a scout observation post and ground surveillance radar site are not colocated within the same condensed area of operations. The second reason is that while the battlefield may be easier to observe, it is not easier to interpret, both due to the impact of adversary deception operations and the need for large amounts of human and machine analytical power to decipher such a vast array of information and turn it into actionable intelligence. Even if successfully gathered and interpreted, this information must still be passed to the appropriate formations and decision-makers within windows of anticipated usefulness.

Second, the rotational brigade also has an array of sensors that must be denied the ability to collect on the OPFOR brigade tactical group (BTG). The transparent battlefield is a double-edged sword. Thus, while the rotational unit and its parent division headquarters may not have quite as many sensors as the OPFOR, they are nonetheless fully capable of not only answering brigade priority intelligence requirements but also identifying and targeting key Blackhorse capabilities and formations, from mechanized infantry platoons to rocket artillery batteries. Already outnumbered nearly eight to one, Blackhorse cannot afford any losses prior to main body contact and must therefore consistently win both the reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance fight. However, Blackhorse combat power limitations also demand that any security or counterreconnaissance mission must be executed as an economy-of-force task and not detract from already limited brigade and division tactical group (DTG) combat power.

Third, the DTG possesses a litany of strike assets, but their employment must be precise and produce measurable effects for the DTG and subordinate BTGs. While the traditional definition of strike within a reconnaissance-strike regime refers to indirect fires capability, the Blackhorse Regiment possesses additional kinetic and nonkinetic means to strike a rotational brigade, including multispectrum jamming, psychological warfare and information operations, and cyberattacks. Yet, use of these assets comes with a dilemma. Although attachment to the BTG may keep such enablers closer to the fight and poised to react to quickly changing battlefield conditions, in practice a BTG staff is nothing more than a battalion staff asked to operate one echelon higher than normal, which means it lacks both the expertise and the bandwidth to fully integrate such enablers. This is especially true for enablers that operate on different regeneration and effect cycles or have wide areas of impact, such as electronic warfare jamming equipment whose employment risks fratricide if not carefully coordinated and planned for. Conversely, centralization at the DTG risks desynchronizing their employment with subordinate unit maneuver and engaging in a deep fight with limited follow-on benefit in the close fight.

Finally, increased capability has demanded increased synchronization. For decades, Blackhorse prioritization of simple, flexible plans easily adaptable to changes in rotational unit battlefield deployment has enabled the regiment to repeatedly outmaneuver its opponents while gaining and maintaining decision dominance. However, as Blackhorse has added more capabilities, the resultant additional synchronization required for their employment has threatened such simplicity and flexibility and risks placing the BTG in a stand-up battle of attrition it is ill-postured to win.

Blackhorse Adaptation

For six months across the fall and winter of 2024–2025, leaders across the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment debated how these four central challenges risked creating an environment in which the regiment could no longer fulfill its mission of preparing units to win the first battle of the next war. Constrained by largely inflexible budgets and personnel limitations like most of the Army, the situation initially looked insurmountable—until the regiment realized that just as “yesterday’s weapons will not win tomorrow’s wars” neither would yesterday’s organizations. The unit’s leadership sought, as an initial and most consequential change, a new organization capable of solving such challenges through a unique meshing of key leaders and capabilities: Centaur Squadron.

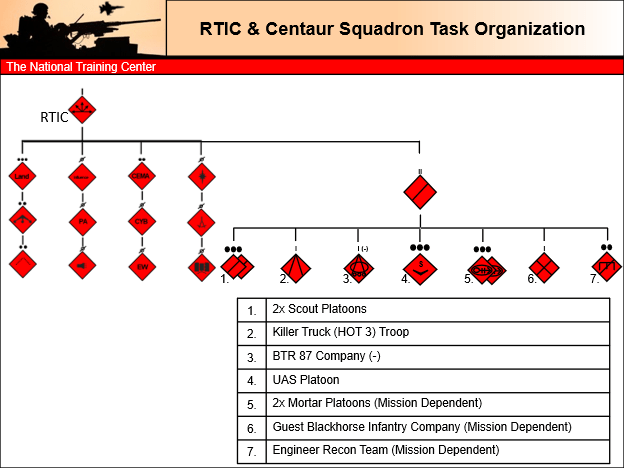

Like the regiment’s mechanized infantry battalions, Centaur is formed by the merging of two troops within the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment: Killer Troop (an antitank troop) and the Regimental Headquarters and Headquarters Troop. While Centaur is a flexible organization tailorable to a specific mission set, its habitual task organization consists of three “Hot 3” antitank platoons and roughly a company of BTR-87 armored personnel carriers from Killer Troop, the regiment’s two scout platoons, and the UAS platoon from the Regimental Headquarters and Headquarters Troop. Killer Troop’s commander acts as Centaur commander and the headquarters troop commander serves as deputy commander.

As an adjacent unit to the BTG, Centaur Squadron works directly for the DTG, specifically the regimental targeting and integration cell (RTIC). The RTIC is where niche enablers including the regimental fires cell, information operations and electronic warfare section, and military intelligence company reside in a lean, hyperfocused targeting cell specifically tasked with enabling the destruction of the rotational brigade along five operational principles.

- Flexible Task Organization. While the core of Centaur’s task organization remains the same, careful analysis of the mission variables will see the formation augmented with BTG mortar platoons, mechanized infantry platoons, and even dismounted infantry squads to assist in its reconnaissance and security mission.

- Manned-Unmanned Teaming. Although cavalry scouts remain the premier regimental reconnaissance asset, attritable unmanned systems allow the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment to extend the depth of its reconnaissance-strike complex and penetrate protected rear areas. This task is assisted by careful regimental unmanned aircraft system (UAS) distribution, based on subordinate element requirements, responsibility within the larger DTG/BTG fight, and capacity to manage UAS employment and synchronization.

- Layered Reconnaissance. Despite the array of sensors on the modern battlefield, any individual sensor not only has hard, baked-in limitations, but is still prone to failure from mechanical malfunction, weather or terrain impediment, and adversary targeting and destruction. Thus, the regiment must still use the reconnaissance management techniques of cueing, mixing, and redundancy to gain and maintain persistent contact with an opposing brigade.

- Intelligence-derived maneuver. The byproduct of persistent adversary contact is a consistent stream of reports that can overwhelm any headquarters not equipped with sufficient staff capacity to handle such a high volume of information. Within the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the RTIC leads the regimental intelligence effort to rapidly analyze gathered information, answer priority information requirements, package intelligence into digestible summaries tied to specific subordinate formation requirements, and disseminate such intelligence to requesting formations down to leading mechanized infantry platoons along the FLOT—the forward line of own troops. This ensures no leader across the regiment makes a decision in combat without the best possible intelligence.

- Tactical control of operational-level enablers. While the RTIC alone possesses the inherent staff capacity to analyze the entirety of the battlefield, its direct management of exquisite regimental enablers risks desynchronization from the tactical fight and reduced effectiveness. Instead, while the RTIC translates the DTG commander’s targeting priorities into targeting guidance at the daily targeting working group based on input from enabler subject matter experts, precise tactical employment and positioning of such capabilities are left to the authority of Centaur leaders. These leaders’ forward location and detailed understanding of the squadron’s arrayal allows for a mission command–based approach to accomplishing the DTG commander’s intent.

While these five operational principles detail how Centaur thinks about fighting, the squadron uses a three-phase model to execute its fight during rotations. The first phase is deployment. This begins with rollout from the Fort Irwin cantonment area and ends once the squadron has fully occupied its security zone in front of the BTG. To ensure maximum survivability of all elements, scout platoon BRDM armored scout vehicles lead Centaur into its area of operations. Mounted observation posts are established by competitively infiltrating to observe templated named areas of interest, enabling ground combat elements to be pulled into cleared battle positions. Once these elements have occupied their battle positions, the final slice of the squadron, its UAS and electronic warfare attack/surveillance teams, move into sector. Selecting positions as close to the forward edge of the security zone as possible maximizes their effects across the depth of the rotational brigade.

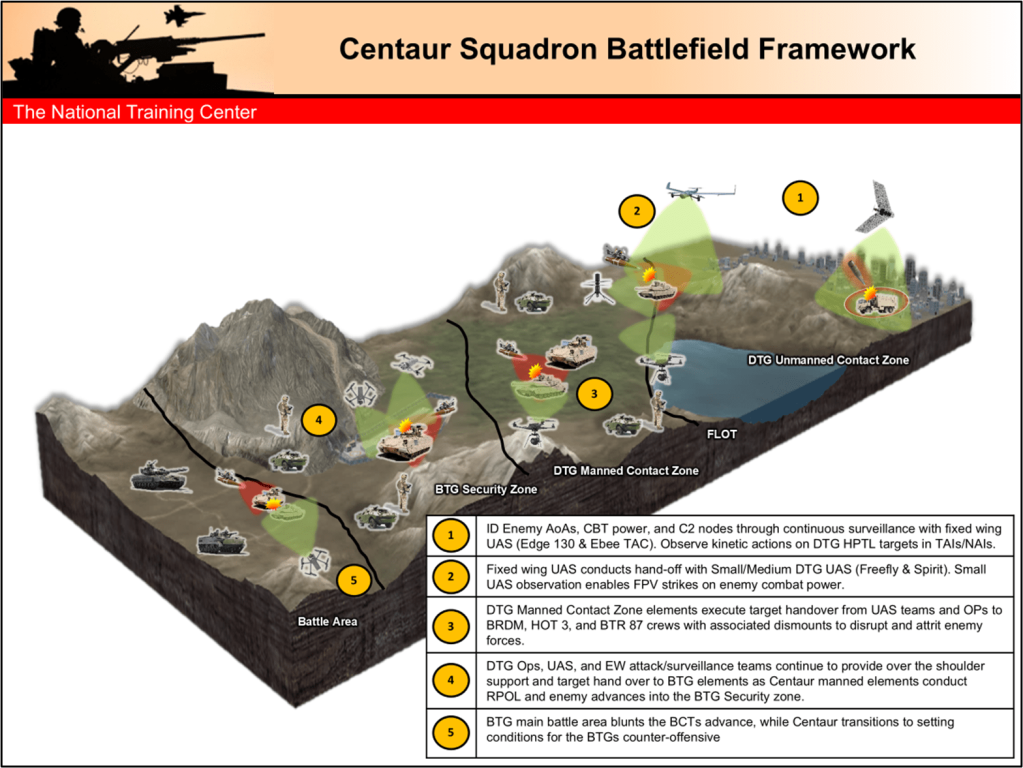

Next comes reconnaissance and security operations. Once established in a security zone, Centaur maintains contact with the rotational brigade until it has reached its preplanned disengagement criteria, at which point it conducts an rearward passage of lines through the BTG. Mimicking observations from both the ongoing war in Ukraine and ongoing adversary adaptations, contact is maintained with the brigade through two contact zones: (1) a manned contact zone occupied by the majority of Centaur’s traditional ground combat power in an area about three to five kilometers deep, depending on terrain, and (2) an unmanned contact zone extending out another five to ten kilometers toward the rotational brigade. Importantly, while both manned elements exist in the unmanned zone and unmanned elements exist in the manned zone, Blackhorse uses these terms to indicate whether manned or unmanned systems compromise the primary reconnaissance-strike elements.

The final phase is over-the-shoulder support. Up until this point, Centaur Squadron has largely mimicked the role of a brigade or division cavalry formation operating in a security zone forward of the main body, just with slightly higher UAS usage and integration with higher-echelon enablers. However, it is during phase three that Centaur truly demonstrates its value to the regiment—and, notably, its value to the larger Army as a model, with its embrace of reconnaissance-strike battle. Even as its Killer Troop antitank capabilities and BTR platoons return to the DTG support area to prepare for follow-on missions, its UAS and electronic warfare attack/surveillance teams occupy subsequent positions within forward mechanized infantry battalion areas of operations. The regiment does not collapse the unmanned and manned contact zones, but rather shifts them with the progress of the rotational brigade, with defending mechanized infantry battalions taking the burden of the manned contact zone while a reduced Centaur Squadron maintains the unmanned zone. This presents the attacking brigade with an uncomfortable reality. Although the BTG’s main battle area doctrinally demands the massing of the rotational brigade’s combat power for a combined arms breach, Centaur’s ability to maintain multiple forms of contact with the brigade out to approximately fifteen kilometers of depth punishes such an approach. Centaur and the DTG thereby continuously shape and attrit an opposing brigade across the depth of its formation in concert with the BTG fight.

At end state, the rotational brigade has culminated short of its objectives. With the combination of Centaur’s reconnaissance-strike complex and the BTG’s prepared defense, the brigade’s ability to mass its superior combat power is disrupted and disintegrated and it is left vulnerable to a concentrated BTG attack against an isolated combined arms battalion. The squadron not only provides over-the-shoulder support to help disrupt the brigade cavalry squadron’s attempt at establishing a security zone, but also uses its UAS to penetrate the brigade’s security zone to target and collect on the brigade within its main battle area. This disrupts the rotational brigade’s defense and helps direct the attacking BTG towards the brigade’s most vulnerable battalion.

Since 1994 the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment has supported the NTC mission of preparing units to win the first fight of the next war. As Krasnovians, Bilasuvar Liberation Front militia, and now Donovians, the regiment has adapted and changed across thirty-one years of dedicated service to best prepare the Army for combat. Today, that adaptation takes the form of Centaur Squadron, a purpose-built reconnaissance and security formation that integrates real world-observations on battlefield tactics, techniques, and procedures into a paradigm of a tactical reconnaissance-strike regime to challenge any Army formation unprepared for the reality of battle within the Mojave Desert. And like our predecessors who shared their observations with their rotational training unit counterparts to best prepare them for real-world operations, we look forward to sharing our own observations, lessons, and best practices with the Army.

The price of failure in combat has never been higher. We cannot be caught unready.

Colonel Kevin Black is an armor officer who currently serves as the 71st colonel of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Irwin, California. Previous assignments include command of 3rd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, multiple staff assignments in the Pentagon, G3 for the 3rd Infantry Division at Fort Stewart, Georgia, and operational deployments to Afghanistan, to Iraq, and in support of the Security Assistance Group Ukraine.

Lieutenant Colonel Tarik Fulcher is an armor officer who currently serves as the regimental deputy commander of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Irwin, California. Previous assignments include executive officer to the commanding general of the Security Assistance Group Ukraine, US Army Europe and Africa G5 plans branch chief, School of Advanced Military Studies, and key developmental positions in the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment and 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Hood, Texas.

Captain Daniel Gaston is an armor officer currently serving as an OC/T at the Joint Multinational Readiness Center in Hohenfels, Germany. Previous assignments include commander of Regimental Headquarters and Headquarters Troop, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment and commander of Dealer Company, 1/11th Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Irwin, California.

Captain Joshua Ratta is an armor officer who currently serves as the commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Troop, 1st Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Irwin, California. Previous assignments include commander of Bravo Troop, 1/11th Armored Cavalry Regiment; tank platoon leader, distribution platoon leader, tank company executive officer, and battalion maintenance officer with 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team at Fort Carson, Colorado.

Captain Ethan Christensen is an infantry officer who currently serves as the commander of Killer Troop, 2nd Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment at Fort Irwin, California. Previous assignments include commander of Easy Troop, 2/11th Armored Cavalry Regiment; Bradley platoon leader, mortar platoon leader, Regionally Aligned Forces Division (FWD) liaison officer, and Headquarters and Headquarters Company executive officer with 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, 2rd Armored Brigade Combat Team at Fort Stewart, Georgia.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the United States Military Academy, Department of the Army, or Department of Defense.

Image credit: Capt. Evan Cain, US Army